In 596 Gregory the Great, bishop of Rome, sent Augustine and other monks to journey to England to evangelise the “angels”. There is that lovely story that tells of Gregory’s visit to a slave market in Rome and saw fair haired youths. When he enquired what race of people they were, he was told Angles. His reply was not Angles but angels. From that moment Gregory had a burning desire to free these youths of their pagan ways and to convert them to Christianity. When he was elected pope in 590 the state of Rome made it imperative he stayed.

Yet he never forgot his intent. He appointed one of the monks from his own abbey of St. Andrew that had originally been his home on the Caelian Hill in Rome. The monk chosen was Augustine. However virtually nothing is known of Augustine’s life before entering this monastery, and if Gregory had not appointed him as his representative to go to England, this Augustine would have died in obscurity.

Yet he never forgot his intent. He appointed one of the monks from his own abbey of St. Andrew that had originally been his home on the Caelian Hill in Rome. The monk chosen was Augustine. However virtually nothing is known of Augustine’s life before entering this monastery, and if Gregory had not appointed him as his representative to go to England, this Augustine would have died in obscurity.

The journey to England was full of frustrations and hazards, even to the point of disillusionment for the monks, so much so that Augustine turned back to Rome when in Gaul to seek advice from Gregory after hearing “horrific stories of barbarity of the Anglis and hard fierce nature of the Saxon race”. Needless to say Gregory sent him back.

The journey to England was full of frustrations and hazards, even to the point of disillusionment for the monks, so much so that Augustine turned back to Rome when in Gaul to seek advice from Gregory after hearing “horrific stories of barbarity of the Anglis and hard fierce nature of the Saxon race”. Needless to say Gregory sent him back.

Eventually Augustine arrived on the island of Thanet, off the Kentish coast at Easter 597, probably at Ebbsfleet (the same year that St. Columba died, the founder of the monastery of Iona from whence came the missionaries who converted northern England). Kent was one of the seven kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England. When Augustine arrived Ethelbert, the king was married to a Christian, Bertha, daughter of the Frankish king Charibert I. She had her own priest and worshipped in the little church of St. Martin’s (still used for worship to-day and a beautiful Roman church it is).

Eventually Augustine arrived on the island of Thanet, off the Kentish coast at Easter 597, probably at Ebbsfleet (the same year that St. Columba died, the founder of the monastery of Iona from whence came the missionaries who converted northern England). Kent was one of the seven kingdoms in Anglo-Saxon England. When Augustine arrived Ethelbert, the king was married to a Christian, Bertha, daughter of the Frankish king Charibert I. She had her own priest and worshipped in the little church of St. Martin’s (still used for worship to-day and a beautiful Roman church it is).

According to Bede, Augustine after landing, sent greetings to Ethelbert who responded that they could stay on the island until he decided what to do with them. On agreeing to meet them Augustine and his monks approached him in prayerful procession behind the crucifer. Ethelbert welcomed them warmly, and agreed to make provision for them in Canterbury by allowing them to worship at St. Martin’s. As they travelled into Canterbury the monks chanted the Rogation Day Litany.

According to Bede, Augustine after landing, sent greetings to Ethelbert who responded that they could stay on the island until he decided what to do with them. On agreeing to meet them Augustine and his monks approached him in prayerful procession behind the crucifer. Ethelbert welcomed them warmly, and agreed to make provision for them in Canterbury by allowing them to worship at St. Martin’s. As they travelled into Canterbury the monks chanted the Rogation Day Litany.

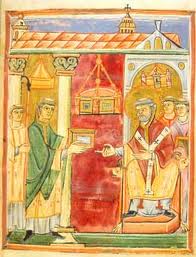

That Whitsun Eve Ethelbert and most of his people were baptised. After that Augustine returned to Gaul to be consecrated bishop by the archbishop of Arles, Etherius, to be Archbishop of the English. Gregory had directed that London become his see, but this never did eventuate, as Augustine and his chair stayed in Canterbury, and ever since has remained as the primal see in England. However the “chair” now in the cathedral is a mediæval replica.

That Whitsun Eve Ethelbert and most of his people were baptised. After that Augustine returned to Gaul to be consecrated bishop by the archbishop of Arles, Etherius, to be Archbishop of the English. Gregory had directed that London become his see, but this never did eventuate, as Augustine and his chair stayed in Canterbury, and ever since has remained as the primal see in England. However the “chair” now in the cathedral is a mediæval replica.

Outside the walls of Canterbury, not far from St. Martin’s was a pagan temple that Ethelbert gave to Augustine who dedicated it to St. Pancras (a child martyr under Dioclectian’s persecution in A.D. 304). On land near this church a monastery dedicated to SS. Peter and Paul was built. (Later on St. Dunstan when he was archbishop of Canterbury in the 10th century changed its name to St. Augustine Abbey). Inside the city walls the church of the Holy Saviour, later dedicated to the Church of Christ, was built. This later became Canterbury Cathedral. Augustine’s cathedra was placed here and has remained ever since as stated.

Outside the walls of Canterbury, not far from St. Martin’s was a pagan temple that Ethelbert gave to Augustine who dedicated it to St. Pancras (a child martyr under Dioclectian’s persecution in A.D. 304). On land near this church a monastery dedicated to SS. Peter and Paul was built. (Later on St. Dunstan when he was archbishop of Canterbury in the 10th century changed its name to St. Augustine Abbey). Inside the city walls the church of the Holy Saviour, later dedicated to the Church of Christ, was built. This later became Canterbury Cathedral. Augustine’s cathedra was placed here and has remained ever since as stated.

After his consecration Augustine sent a letter to Gregory via the hands of Laurence the priest and Peter the monk seeking advice on such matters as the liturgy, the various customs in the churches, the consecration of new bishops when bishops lived far apart, and various moral and spiritual issues. Gregory’s reply revealed the compassionate and pastoral bishop he was. He suggested that local Church customs should be maintained. He advised Augustine not to eradicate the shrines of the pagans but to convert them to churches and to replace heathen rituals with Christian worship. He also directed him to contact the British bishops to help him in missionary work, and sent a scheme to reorganize the English Church. Gregory envisaged twelve dioceses with London in the south and York in the north being the principal sees. This never eventuated until much later.

After his consecration Augustine sent a letter to Gregory via the hands of Laurence the priest and Peter the monk seeking advice on such matters as the liturgy, the various customs in the churches, the consecration of new bishops when bishops lived far apart, and various moral and spiritual issues. Gregory’s reply revealed the compassionate and pastoral bishop he was. He suggested that local Church customs should be maintained. He advised Augustine not to eradicate the shrines of the pagans but to convert them to churches and to replace heathen rituals with Christian worship. He also directed him to contact the British bishops to help him in missionary work, and sent a scheme to reorganize the English Church. Gregory envisaged twelve dioceses with London in the south and York in the north being the principal sees. This never eventuated until much later.

Augustine soon discovered that the island was not entirely heathen. After all there had been bishops there for at least three and a half centuries. Three had attended the Council of Arles in A.D 314. He arranged to meet the British bishops near the Welsh border in either 602 or 603 in order to persuade them to adopt Roman usages, practices and time for Easter as well their cooperation to convert the heathen. The British bishops asked for time to consider Augustine’s proposals, and so a second conference was arranged. To this came seven British bishops and many learned men. It is said that as they set out they consulted a holy hermit for advice on whether they should accept Augustine’s proposals. His advice was, to accept these proposals if he is a true servant of Christ. How shall we know that, they enquired? If he is humble, came the reply. So the hermit advised the bishops to arrive after Augustine, and if he rises to welcome you, you will know that he is a true servant of Christ. However on their arrival Augustine remained seated, and so they took him to be a proud man, and consequently they argued against everything that Augustine said. Whether this is the real reason for lack of co-operation is uncertain; perhaps nearer the truth is the deep cultural and ecclesiastic differences between the Celtic and Roman churches.

Gregory supported Augustine as much as he could by correspondence, gifts of ecclesiastical materials, books, and by sending more help. Accordingly in 1601 a second group of missionaries arrived from Rome. Among these new missionaries were Mellitus, Justus, Paulinus and Rufinianius. Included in Gregory’s gifts were sacred vessels, double cross, seamless tunic, altar draperies, church ornaments, vestments for bishops and priests, relics of holy martyrs and a quantity of books. He also sent the Pallium to Augustine, which symbolised his metropolitan jurisdiction

Gregory supported Augustine as much as he could by correspondence, gifts of ecclesiastical materials, books, and by sending more help. Accordingly in 1601 a second group of missionaries arrived from Rome. Among these new missionaries were Mellitus, Justus, Paulinus and Rufinianius. Included in Gregory’s gifts were sacred vessels, double cross, seamless tunic, altar draperies, church ornaments, vestments for bishops and priests, relics of holy martyrs and a quantity of books. He also sent the Pallium to Augustine, which symbolised his metropolitan jurisdiction

In 1604 Augustine consecrated Justus to be bishop of Rochester, the second oldest see in England, and Mellitus as bishop of London who converted the old pagan temple to a church. This was consecrated and dedicated to St. Paul. Years later a magnificent cathedral rose on this site only to be burned to the ground during the Great Fire of 1666.

In 1604 Augustine consecrated Justus to be bishop of Rochester, the second oldest see in England, and Mellitus as bishop of London who converted the old pagan temple to a church. This was consecrated and dedicated to St. Paul. Years later a magnificent cathedral rose on this site only to be burned to the ground during the Great Fire of 1666.

Paulinus became Ethelberga’s chaplain (daughter of Bertha and Ethelbert), and accompanied her north when she married Edwin of Northumbria in 1625. A similar situation occurred here as in Kent. Edwin chose to be baptised by Paulinus, and many of his people followed. With Edwin’s help Paulinus established his see at York. After Edwin was killed by the heathen king, Penda, Paulinus and Ethelberga returned to Kent.

Paulinus became Ethelberga’s chaplain (daughter of Bertha and Ethelbert), and accompanied her north when she married Edwin of Northumbria in 1625. A similar situation occurred here as in Kent. Edwin chose to be baptised by Paulinus, and many of his people followed. With Edwin’s help Paulinus established his see at York. After Edwin was killed by the heathen king, Penda, Paulinus and Ethelberga returned to Kent.

One of Augustine’s last act was to consecrate Lawrence as a bishop and to be his successor. He in turn was followed by Mellitus in 619.

One of Augustine’s last act was to consecrate Lawrence as a bishop and to be his successor. He in turn was followed by Mellitus in 619.

St. Augustine died in either 604 or 605 on 24th or 26th May. He was buried outside the church of SS. Peter and Paul for it was not yet finished and therefore not consecrated. After it was consecrated, Augustine’s body was placed inside in the chapel of St. Gregory on the northern side. At the Council of Clovesho in 747 it was decreed that the 26th May should be kept as the feast of St. Augustine.

St. Augustine died in either 604 or 605 on 24th or 26th May. He was buried outside the church of SS. Peter and Paul for it was not yet finished and therefore not consecrated. After it was consecrated, Augustine’s body was placed inside in the chapel of St. Gregory on the northern side. At the Council of Clovesho in 747 it was decreed that the 26th May should be kept as the feast of St. Augustine.

What did Augustine actually achieve? In terms of converting the seven kingdoms in England very little. His legacy is the diocese of Canterbury and nearby Rochester and London dioceses. Of course Canterbury Cathedral is his main legacy to Christianity, and the monastery he established became an important centre for learning. The conversion of England would take almost another sixty years or so and it would be a joint effort of both the Celtic and Roman Churches.

What did Augustine actually achieve? In terms of converting the seven kingdoms in England very little. His legacy is the diocese of Canterbury and nearby Rochester and London dioceses. Of course Canterbury Cathedral is his main legacy to Christianity, and the monastery he established became an important centre for learning. The conversion of England would take almost another sixty years or so and it would be a joint effort of both the Celtic and Roman Churches.

Yet there were great differences between these two churches. As Peter Blair explained:

Yet there were great differences between these two churches. As Peter Blair explained:

Conflict between the Roman and Celtic Churches in Britain was inevitable. During it long period of isolation the Celtic Church had developed in complete independence and had diverged considerabl from the paths followed by Rome, not merely in the matters of form and ritual, but more fundamentally in its whole organization. Rome could not readily brook the continued existence of what it regarded as schismatic ways and still less could it contemplate so large a Christian community which showed remarkable missionary zeal should not recognize the pope as its spiritual head. But on the other side, the Celtic Church, as some of its members realized, could not afford to ignore the benefits which Rome, representing by far the greater part of Christendom, had to offer (An Introduction to Anglo-Saxon England, 1977, p. 129).

One of those main differences was over the calendar. Both churches held Easter at different times. To settle these differences what is known as the Synod of Whitby was convened in 664 under Hilda’s overseeing. After much debate it was recognised it was more profitable for the English church to be part of an universal church. It was thus decided to adopt the Roman church’s customs.

This is the inscription on Agustine's tomb:

Here lies the most reverend Augustine

Here lies the most reverend Augustine

First Archbishop of Canterbury,

First Archbishop of Canterbury,

Who was formerly sent by St. Gregory, bishop of Rome;

Who was formerly sent by St. Gregory, bishop of Rome;

Being supported by God in the working of miracles,

He led King Ethelbert and his nation from the worship of idols

He led King Ethelbert and his nation from the worship of idols

To faith in Christ

And ended the days of his office in peace

He died on the twenty-sixth day of May during the reign

Of the same King.