LISTEN CAREFULLY, MY SON, TO THE MASTER'S INSTRUCTIONS.

EVERY TIME YOU BEGIN A GOOD WORK, YOU MUST PRAY TO HIM MOST EARNESTLY TO BRING IT ABOUT.

FIRST OF ALL, LOVE THE LORD GOD WITH ALL YOUR HEART, YOUR WHOLE SOUL AND ALL YOUR STRENGTH, AND LOVE YOUR NEIGHBOUR AS YOURSELF.

NO ONE IS TO PURSUE WHAT HE JUDGES BETTER FOR HIMSELF, BUT INSTEAD, WHAT HE JUDGES BETTER FOR SOMEONE ELSE.

ALL GUESTS, WHO PRESENT THEMSELVES ARE TO BE WELCOMED AS CHRIST.

MONKS SHOULD DILIGENTLY CULTIVATE SILENCE AT ALL TIMES, BUT ESPECIALLY AT NIGHT.

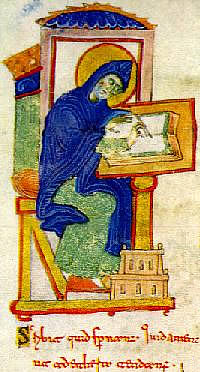

When the monks from Monte Casino fled to Rome as their monastery was attacked by the invading Lombards in 581, they took with them, among other treasures, a copy of the Rule “which the holy Father had composed”. It was this Rule, which came to shapeWestern Christendom for over a thousand years, and the holy Father who composed it, Benedict, is the patron of Europe.

Benedict was born in Nursia, near Perugia, in central Italy, c. 480 at a time of great turmoil as the dying Roman Empire gave way to the onslaught of various Barbarian invasions. As a young man Benedict had been sent to Rome to study but appalled by its decadence and corruption he abandoned his studies to search for God. Hence for three years he lived a hermit’s life in a cave at Subiaco. His holiness of life attracted others to him, which in due course led to the establishing of small communities in the neighbourhood, but some soon became disgruntled about the high standard of living imposed on them by Benedict. So Benedict returned to solitude but once again the same thing happened - others were attracted to him, and a community began, only to be fragmented once again by the worldly members. This time Benedict took the faithful monks with him to Monte Cassino. Here he built up a community over the years that came to be organised on the Rule which Benedict laid down for his monks.

Benedict was born in Nursia, near Perugia, in central Italy, c. 480 at a time of great turmoil as the dying Roman Empire gave way to the onslaught of various Barbarian invasions. As a young man Benedict had been sent to Rome to study but appalled by its decadence and corruption he abandoned his studies to search for God. Hence for three years he lived a hermit’s life in a cave at Subiaco. His holiness of life attracted others to him, which in due course led to the establishing of small communities in the neighbourhood, but some soon became disgruntled about the high standard of living imposed on them by Benedict. So Benedict returned to solitude but once again the same thing happened - others were attracted to him, and a community began, only to be fragmented once again by the worldly members. This time Benedict took the faithful monks with him to Monte Cassino. Here he built up a community over the years that came to be organised on the Rule which Benedict laid down for his monks.

The first monks in Christendom had lived as Benedict did in his early life, as hermits. In the Eastern Church under the great St. Basil in the fourth century, monasticism came to be based on cenobitic living as he believed that no man could love God until he loved his brethren first. So he drew up a monastic rule based on community living. It was this pattern that Benedict followed as he also realised that spiritual progress can only be made when individuals constantly make an effort to see Christ in every person, and bear one another’s burdens.

There were seventy-three chapters in the Benedictine Rule, of which the oldest surviving copy is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Nine treat the duties of the abbot, thirteen regulate the worship of God, twenty-nine set out the discipline and penal code, ten are concerned with internal administration, and the other twelve with miscellaneous regulations.

There were seventy-three chapters in the Benedictine Rule, of which the oldest surviving copy is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Nine treat the duties of the abbot, thirteen regulate the worship of God, twenty-nine set out the discipline and penal code, ten are concerned with internal administration, and the other twelve with miscellaneous regulations.

Benedict adopted a sensible and sensitive approach for his Rule or what he called it “a little rule for beginners” [the great rule for Benedict was the Holy Scriptures]; there was to be “nothing harsh, nothing burdensome”. For Benedict living the monastic and Christian life was not to be handicapped with austerities and hurdles, which so often crushed the essence of true devotion. In fact it is a rule that every Christian can live by, even in to-day’s world. He envisaged a life balanced between prayer and work. Monks spent time praying in order to discover why they worked, and they spent time working so that good order and harmony would prevail in the monastery. Hence all monks from the youngest to the most educated had to be engaged in some manual work every day. From this concept the great Benedictine motto was established – Laborare est orare.

Benedict adopted a sensible and sensitive approach for his Rule or what he called it “a little rule for beginners” [the great rule for Benedict was the Holy Scriptures]; there was to be “nothing harsh, nothing burdensome”. For Benedict living the monastic and Christian life was not to be handicapped with austerities and hurdles, which so often crushed the essence of true devotion. In fact it is a rule that every Christian can live by, even in to-day’s world. He envisaged a life balanced between prayer and work. Monks spent time praying in order to discover why they worked, and they spent time working so that good order and harmony would prevail in the monastery. Hence all monks from the youngest to the most educated had to be engaged in some manual work every day. From this concept the great Benedictine motto was established – Laborare est orare.

Benedict also believed in moderation in all things – eating, drinking, sleeping, studying and reading as well as prayer and work. Thus the monks were permitted two decent meals a day, although there was no meat, except for the infirmed, but there was a daily allowance of a pound of bread and half a pint of wine. Monks were allowed a good night’s sleep in a proper bed in order to pray, study and work well for the next day.

Benedict also believed in moderation in all things – eating, drinking, sleeping, studying and reading as well as prayer and work. Thus the monks were permitted two decent meals a day, although there was no meat, except for the infirmed, but there was a daily allowance of a pound of bread and half a pint of wine. Monks were allowed a good night’s sleep in a proper bed in order to pray, study and work well for the next day.

The heart of the rule was the Opus Dei, and nothing was to be put before the saying of the daily offices throughout the day. This was the great work of the community to recite the psalms and respective office hymn seven times a day. Benedict was practical enough to realise that long offices are not always inductive to fruitful prayers, and so the Offices were short enough not to make praying wearisome, but monks were expected at all times to reverence the presence of God. After the evening meal the greater silence was practised, and thus the reason for the first response at Lauds “O Lord open thou our lips”. However during the day the monks were expected to exercise commonsense in regards to talking.

The heart of the rule was the Opus Dei, and nothing was to be put before the saying of the daily offices throughout the day. This was the great work of the community to recite the psalms and respective office hymn seven times a day. Benedict was practical enough to realise that long offices are not always inductive to fruitful prayers, and so the Offices were short enough not to make praying wearisome, but monks were expected at all times to reverence the presence of God. After the evening meal the greater silence was practised, and thus the reason for the first response at Lauds “O Lord open thou our lips”. However during the day the monks were expected to exercise commonsense in regards to talking.

Next to loving and worshipping God was to love one’s brethren. “Let monks … in honour prefer one another. Let them vie in paying obedience one to another,” stated the Rule. It also meant that hospitality was a main part of a Benedictine monastery. The Rule stipulated “let everyone that comes be received as Christ”

Next to loving and worshipping God was to love one’s brethren. “Let monks … in honour prefer one another. Let them vie in paying obedience one to another,” stated the Rule. It also meant that hospitality was a main part of a Benedictine monastery. The Rule stipulated “let everyone that comes be received as Christ”

Stewardship was another important aspect of the Rule and the monks were taught to value all things - the garden hoe was as important as the chalice in its own way. All property was communal and thus there was no personal possession. Whatever task the monk was doing, even when it was hard or odious or both, he was expected to do it with cheerfulness and for the welfare of the whole community.

Stewardship was another important aspect of the Rule and the monks were taught to value all things - the garden hoe was as important as the chalice in its own way. All property was communal and thus there was no personal possession. Whatever task the monk was doing, even when it was hard or odious or both, he was expected to do it with cheerfulness and for the welfare of the whole community.

When the monks were professed they took three vows: Stability, a lifelong commitment to the community; fidelity to the monastic rule, so that at the sound of the bell for prayer all other activities ceased, and obedience to the Abbot.

When the monks were professed they took three vows: Stability, a lifelong commitment to the community; fidelity to the monastic rule, so that at the sound of the bell for prayer all other activities ceased, and obedience to the Abbot.

Of course the main reason for the monks to live under vows and by rules is to discipline, shape and indeed transform their lives in order to draw closer to Christ and to live by His teachings. Hence another rule stressed the importance of reading and studying the Holy Scriptures. That Great Rule, had to be read in order to know what Christ taught, one of which was about the virtue of humility, which featured in the Rule. It was only by practising this virtue that the path was found to heaven.

Of course the main reason for the monks to live under vows and by rules is to discipline, shape and indeed transform their lives in order to draw closer to Christ and to live by His teachings. Hence another rule stressed the importance of reading and studying the Holy Scriptures. That Great Rule, had to be read in order to know what Christ taught, one of which was about the virtue of humility, which featured in the Rule. It was only by practising this virtue that the path was found to heaven.

What Benedict did was to take ordinary people and give them a new direction and purpose to life by putting God as the focus of their lives. Rule seventy-two states “… let us prefer nothing whatever to Christ, and may he bring us all to eternal life.” That message is still true for us to-day – as we draw closer to God in prayer, we shall want to outreach to those in need in our world and share the Gospel with them.

What Benedict did was to take ordinary people and give them a new direction and purpose to life by putting God as the focus of their lives. Rule seventy-two states “… let us prefer nothing whatever to Christ, and may he bring us all to eternal life.” That message is still true for us to-day – as we draw closer to God in prayer, we shall want to outreach to those in need in our world and share the Gospel with them.

Undoubtedly Benedict’s Rule is a masterpiece of spiritual and earthly wisdom, and the fact that it has endured for 1500 years is a testimony to its wisdom. Something of Benedict’s own personality can be seen from his description of the abbot in the Rule – he had to be wise, discreet, flexible, learned in the law of God, but also a spiritual father to his community. Thus it was quite appropriate then that when Pope Paul VI visited Monte Cassino in 1964 he should declare Benedict the main patron of Europe.

Undoubtedly Benedict’s Rule is a masterpiece of spiritual and earthly wisdom, and the fact that it has endured for 1500 years is a testimony to its wisdom. Something of Benedict’s own personality can be seen from his description of the abbot in the Rule – he had to be wise, discreet, flexible, learned in the law of God, but also a spiritual father to his community. Thus it was quite appropriate then that when Pope Paul VI visited Monte Cassino in 1964 he should declare Benedict the main patron of Europe.

So let us all try to practise what Benedict sought for himself and his monks, to live in and with Christ, and we thank God for the wisdom and diligence, sense and sensitivity of blessed Benedict whose departure from this life on 21st March, 547 seemed like a sunbeam.

For many of us Benedict lives on in our hearts as we pray his prayer frequently, and I would like to finish with it:

Gracious and holy Father give us wisdom to perceive you,

Gracious and holy Father give us wisdom to perceive you,

diligence to seek you, patience to wait upon you,

diligence to seek you, patience to wait upon you,

eyes to behold you, a heart to meditate upon you,

eyes to behold you, a heart to meditate upon you,

and a life to proclaim you through the power of

and a life to proclaim you through the power of

the Spirit in Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

the Spirit in Jesus Christ our Lord. Amen.

Marianne Dorman