"As if it were a symbol of the life he lived, built together from little acts of kindness and little sacrifices of self, stone by stone and arch by arch rose the Abbey Church of Westminster, which for all the additions and the restorations that have altered it in the course of the centuries, we still call his church." [Occasional Sermons of Ronald Knox, p. 28]

So Edward the Confessor, the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England is best known for the building of Westminster Abbey and for his saintliness. Many healings were attributed to this pious and gentle king. So much so that this became known as "the King's touch".

So Edward the Confessor, the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings of England is best known for the building of Westminster Abbey and for his saintliness. Many healings were attributed to this pious and gentle king. So much so that this became known as "the King's touch".

Edward's life and rule were at a time when much of England was dominated by outside rulers and influences, especially by the Vikings. Born at Islip, just outside Oxford in c.1004, Edward was the son of King Ethelred II 'the Unready' and his Norman wife, Emma, daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy. When he was quite young the Danes invaded England yet again, and Edward was sent to Normandy with his Mother in 1013. Previous to this he was reared at Ely abbey, near Cambridge. When Edward's father died in 1015 and Edmund Ironside, his successor in 1016, the Danish king, Cnut who was already King in the Danelaw parts of England became king of all England. This was strengthened when he married Edward's mother. Meanwhile Edward remained in Normandy. It has been suggested that it was while here that he learnt qualities such as "opportunism and flexibility, patience, caution and worldly wisdom" which enabled him to rule England successfully when he was crowned king of that island. (Barlow)

Edward's life and rule were at a time when much of England was dominated by outside rulers and influences, especially by the Vikings. Born at Islip, just outside Oxford in c.1004, Edward was the son of King Ethelred II 'the Unready' and his Norman wife, Emma, daughter of Duke Richard I of Normandy. When he was quite young the Danes invaded England yet again, and Edward was sent to Normandy with his Mother in 1013. Previous to this he was reared at Ely abbey, near Cambridge. When Edward's father died in 1015 and Edmund Ironside, his successor in 1016, the Danish king, Cnut who was already King in the Danelaw parts of England became king of all England. This was strengthened when he married Edward's mother. Meanwhile Edward remained in Normandy. It has been suggested that it was while here that he learnt qualities such as "opportunism and flexibility, patience, caution and worldly wisdom" which enabled him to rule England successfully when he was crowned king of that island. (Barlow)

Edward the Confessor returned to the English Court at the invitation of his half-brother, King Hardicnut, a year before he died in 1042. Largely through the support of Earl Godwin Edward was acclaimed King of the English, and two year later married the Earl's daughter. Although Edward ruled mainly through the support of the English, he nevertheless surrounded himself with Norman favourites. His rule brought over twenty years of peace despite the undercurrent struggle between Godwin supporters and the Normans. One was caused when the Norman, Robert Champart, Bishop of London, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Edward. The Godwins were banished from the kingdom after staging an unsuccessful rebellion, but they returned the following year in 1052, landing in the south of England. As they received great popular support Edward was forced to restore them to favour in 1053.

Edward the Confessor returned to the English Court at the invitation of his half-brother, King Hardicnut, a year before he died in 1042. Largely through the support of Earl Godwin Edward was acclaimed King of the English, and two year later married the Earl's daughter. Although Edward ruled mainly through the support of the English, he nevertheless surrounded himself with Norman favourites. His rule brought over twenty years of peace despite the undercurrent struggle between Godwin supporters and the Normans. One was caused when the Norman, Robert Champart, Bishop of London, was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury by Edward. The Godwins were banished from the kingdom after staging an unsuccessful rebellion, but they returned the following year in 1052, landing in the south of England. As they received great popular support Edward was forced to restore them to favour in 1053.

Edward was not an ambitious man, he was more content to feed the poor and to give shelter to strangers. As a young man he had made a vow to go on Pilgrimage to Rome, but once he became king he felt to do so would be an irresponsible act towards his kingdom. Instead he decided to found a monastery dedicated to St. Peterf. Thus Edward's greatest achievement was the construction of the Abbey, where virtually all English monarchs from William the Conqueror (the next crowned king) onwards have been crowned. Instead of building a new minster in London, Edward decided to refound an existing house at Thorney to the west of the city, hence the name Westminster, and it to be always under royal patronage. This Abbey was also to be the home for Benedictine monks who had lived at Westminster before Edward's coming, which it was for over five centuries, and there is still a close connection with the Benedictines. This abbey was consecrated at Christmas, 1065, but Edward could not attend due to illness. On his death-bed, Edward named Harold as his successor to the throne. Yet his close ties to Normandy prepared the way for the conquest of England by Normans under William, Duke of Normandy (later King William I or William the Conqueror), in 1066.

Edward was not an ambitious man, he was more content to feed the poor and to give shelter to strangers. As a young man he had made a vow to go on Pilgrimage to Rome, but once he became king he felt to do so would be an irresponsible act towards his kingdom. Instead he decided to found a monastery dedicated to St. Peterf. Thus Edward's greatest achievement was the construction of the Abbey, where virtually all English monarchs from William the Conqueror (the next crowned king) onwards have been crowned. Instead of building a new minster in London, Edward decided to refound an existing house at Thorney to the west of the city, hence the name Westminster, and it to be always under royal patronage. This Abbey was also to be the home for Benedictine monks who had lived at Westminster before Edward's coming, which it was for over five centuries, and there is still a close connection with the Benedictines. This abbey was consecrated at Christmas, 1065, but Edward could not attend due to illness. On his death-bed, Edward named Harold as his successor to the throne. Yet his close ties to Normandy prepared the way for the conquest of England by Normans under William, Duke of Normandy (later King William I or William the Conqueror), in 1066.

Edward died on 5th January, 1066, and his body rests in Westminster Abbey. The contemporary Anglo-Saxon Chronicle expressed sadness at the lost of "so dear a lord, a noble king". As the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings Edward had been determined to keep his kingdom in peace. His rule should never be seen as a prologue to the Norman invasion, and thus dwarfed by the feats of William the Conqueror. A century later in 1161 Alexander III conferred on him the title of confessor.

Edward died on 5th January, 1066, and his body rests in Westminster Abbey. The contemporary Anglo-Saxon Chronicle expressed sadness at the lost of "so dear a lord, a noble king". As the last of the Anglo-Saxon kings Edward had been determined to keep his kingdom in peace. His rule should never be seen as a prologue to the Norman invasion, and thus dwarfed by the feats of William the Conqueror. A century later in 1161 Alexander III conferred on him the title of confessor.

To-day one can read this inscription on his shrine: "Edward the Confessor built the great Abbey Church at this site. His body still rests in the shrine which Henry III caused to be erected in 1268. And here, as founder of Westminster Abbey, his memory has ever been held in honour and grateful remembrance."

To-day one can read this inscription on his shrine: "Edward the Confessor built the great Abbey Church at this site. His body still rests in the shrine which Henry III caused to be erected in 1268. And here, as founder of Westminster Abbey, his memory has ever been held in honour and grateful remembrance."

Yet the shrine to-day is only a shadow of its former self. It originally had three tiers, all richly decorated. To the shrine came many pilgrims, and the sick were often left beside it overnight in the hope of cure. But alas the Reformation dismantled the shrine. Queen Mary partially restored the shrine. Now it is lovingly looked after to honour this blessed king and saint.

Yet the shrine to-day is only a shadow of its former self. It originally had three tiers, all richly decorated. To the shrine came many pilgrims, and the sick were often left beside it overnight in the hope of cure. But alas the Reformation dismantled the shrine. Queen Mary partially restored the shrine. Now it is lovingly looked after to honour this blessed king and saint.

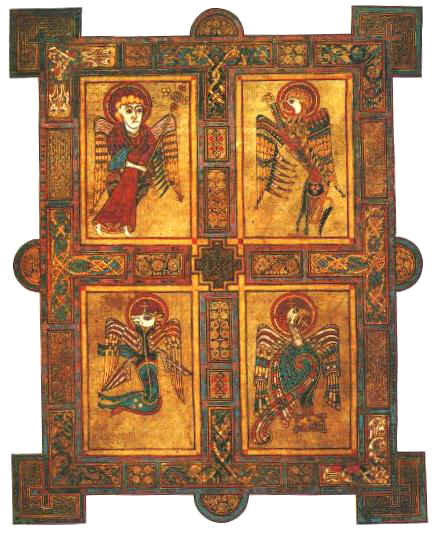

In the library of Cambridge university there is a 13th C manuscript of Illuminations of the life of Edward the Confessor. These include him as a young man kneeling before an altar; sailing to England from Normandy to be crowned; his coronation; his intention to go on pilgrimage; various healings by him; ordering the construction of the Abbey; receiving the Papal charter; his vision of Christ at the elevation of the Host; receiving the last rites; burial; healings at his tomb.

In the library of Cambridge university there is a 13th C manuscript of Illuminations of the life of Edward the Confessor. These include him as a young man kneeling before an altar; sailing to England from Normandy to be crowned; his coronation; his intention to go on pilgrimage; various healings by him; ordering the construction of the Abbey; receiving the Papal charter; his vision of Christ at the elevation of the Host; receiving the last rites; burial; healings at his tomb.

This extract from The Life of King Edward who rests at Westminster, attributed to a monk of St Bertin, describes those last days of this pious king, and his deathbed scene.

"When the one thousand and sixtyfifth year of the Lord's incarnation approached, the zeal of the house of God took possession of King Edward's mind even more warmly, and fired him to the marrow to celebrate the marriage of the heavenly King and his new bride. For it was not the royal sceptre which aroused this love of justice: he found it hidden within him. And so, while the building of the church dedicated to St Peter the Prince of the Apostles at Westminster rose into a lofty structure, the glorious king began with duteous zeal to devote himself to the business of this important consecration. He had also become aware of the approaching end of his mortal life and was drawn to the execution of his good purpose before he should reach life's bourn.

"When the one thousand and sixtyfifth year of the Lord's incarnation approached, the zeal of the house of God took possession of King Edward's mind even more warmly, and fired him to the marrow to celebrate the marriage of the heavenly King and his new bride. For it was not the royal sceptre which aroused this love of justice: he found it hidden within him. And so, while the building of the church dedicated to St Peter the Prince of the Apostles at Westminster rose into a lofty structure, the glorious king began with duteous zeal to devote himself to the business of this important consecration. He had also become aware of the approaching end of his mortal life and was drawn to the execution of his good purpose before he should reach life's bourn.

At that time the days of the Lord's nativity were approaching, and those men for whom throughout the kingdom the heralds of this great dedication were sounding, had added the joys of the one festival to the other. But on the very night on which the Virgin in childbed gave the light of heavenly glory to those who had been darkened by the shadow of death, and, unstained, brought forth without travail the King of Ages, the glorious King Edward was afflicted with an indisposition, and in the palace the day's rejoicing was checked by a fresh calamity. The holy man disguised his sickness more than his strength warranted, and for three days he was able to produce a serene countenance. He sat at table clad in a festal robe, but had no stomach for the delicacies which were served. He showed a cheerful face to the bystanders, although an unbearable weakness oppressed him. But after the banquet he sought the privacy of his inner bedchamber, and bore with patience a distress which grew severer day by day. The close ranks of his vassals surrounded him, and the queen herself was there, in her mourning foretelling future grief. When that celebrated day, which the blessed passion of the Holy Innocents adorns, had come, the excellent prince ordered them to hasten on with the dedication of the church and no more to put it off to another time.

At that time the days of the Lord's nativity were approaching, and those men for whom throughout the kingdom the heralds of this great dedication were sounding, had added the joys of the one festival to the other. But on the very night on which the Virgin in childbed gave the light of heavenly glory to those who had been darkened by the shadow of death, and, unstained, brought forth without travail the King of Ages, the glorious King Edward was afflicted with an indisposition, and in the palace the day's rejoicing was checked by a fresh calamity. The holy man disguised his sickness more than his strength warranted, and for three days he was able to produce a serene countenance. He sat at table clad in a festal robe, but had no stomach for the delicacies which were served. He showed a cheerful face to the bystanders, although an unbearable weakness oppressed him. But after the banquet he sought the privacy of his inner bedchamber, and bore with patience a distress which grew severer day by day. The close ranks of his vassals surrounded him, and the queen herself was there, in her mourning foretelling future grief. When that celebrated day, which the blessed passion of the Holy Innocents adorns, had come, the excellent prince ordered them to hasten on with the dedication of the church and no more to put it off to another time.

When he was sick unto death and his men stood and wept bitterly, King Edward said, 'Do not weep, but intercede with God for my soul and give me leave to go to him. For he will not pardon me so that I shall not die who would not pardon himself so that he should not die.' [Then he addressed his last words to Edith, his Queen, who was sitting at his feet, in this wise: 'May God be gracious to this my wife for the zealous solicitude of her service. For she has served me devotedly, and has always stood close by my side like a beloved daughter.' And stretching forth his hand to his governor, her brother, Harold, he said: 'I commend this woman and all the kingdom to your protection. ... Let the grave for my burial be prepared in the Minster in the place which shall be assigned. I ask that you do not conceal my death, but announce it promptly in all parts, so that all the faithful can beseech the mercy of Almighty God on me, a sinner.] Now and then he also comforted the queen, who ceased not from lamenting, to ease her natural grief. 'Fear not,' he said, '1 shall not die now, but by God's mercy regain my strength.' Nor did he mislead the attentive, least of all himself, by these words, for he has not died, but has passed from death to life, to live with Christ.

When he was sick unto death and his men stood and wept bitterly, King Edward said, 'Do not weep, but intercede with God for my soul and give me leave to go to him. For he will not pardon me so that I shall not die who would not pardon himself so that he should not die.' [Then he addressed his last words to Edith, his Queen, who was sitting at his feet, in this wise: 'May God be gracious to this my wife for the zealous solicitude of her service. For she has served me devotedly, and has always stood close by my side like a beloved daughter.' And stretching forth his hand to his governor, her brother, Harold, he said: 'I commend this woman and all the kingdom to your protection. ... Let the grave for my burial be prepared in the Minster in the place which shall be assigned. I ask that you do not conceal my death, but announce it promptly in all parts, so that all the faithful can beseech the mercy of Almighty God on me, a sinner.] Now and then he also comforted the queen, who ceased not from lamenting, to ease her natural grief. 'Fear not,' he said, '1 shall not die now, but by God's mercy regain my strength.' Nor did he mislead the attentive, least of all himself, by these words, for he has not died, but has passed from death to life, to live with Christ.

And so, coming with these and like words to his last hour, he took the viaticum from the table of heavenly life and gave up his spirit to God the creator on the fourth of January. They bore his holy remains from his palace home into the house of God, and offered up prayers and sighs and psalms all that day and the following night. And before the altar of St Peter the Apostle, the body, washed by his country's tears, was laid up in sight of God."

And so, coming with these and like words to his last hour, he took the viaticum from the table of heavenly life and gave up his spirit to God the creator on the fourth of January. They bore his holy remains from his palace home into the house of God, and offered up prayers and sighs and psalms all that day and the following night. And before the altar of St Peter the Apostle, the body, washed by his country's tears, was laid up in sight of God."

O God, who didst call thy servant Edward to an earthly throne that he might advance thy heavenly kingdom, and didst give him zeal for thy Church and love for thy people: Mercifully grant that we who commemorate him this day may be fruitful in good works, and attain to the glorious crown of thy saints; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

O God, who didst call thy servant Edward to an earthly throne that he might advance thy heavenly kingdom, and didst give him zeal for thy Church and love for thy people: Mercifully grant that we who commemorate him this day may be fruitful in good works, and attain to the glorious crown of thy saints; through Jesus Christ our Lord, who lives and reigns with thee and the Holy Spirit, one God, for ever and ever. Amen.

[We commemorate Edward the confessor on 13th October.] For a time he was patron saint of England until replaced by George when the Crusades were so popular.