Sermon Preached at St. Cross, Oxford on 28th September, 1997,3 days after the commemoration of Lancelot Andrewes.

Text Matthew 6.30

+ In the name of the Father, Son and the Holy Spirit. Amen.

The readings to-day give us various degrees of faith: the awakening to God's presence as expressed in Jacob's vision (an appropriate reading also for to-morrow when we celebrate St. Michael and all Angels); the setting out into the unknown as seen in Abraham's obedience to God's command; and the trusting in God completely to provide us with our daily needs as taught by our blessed Lord. We are to "take no thought for" our lives, we are not be reoccupied with possession, food, drink nor clothing, but simply to your Cross to cling. Christ's teaching is in direct contrast with that of the world with its emphasis on the accumulation of success and wealth. So it is not surprising that Christ told us that we could not serve both God and Mammon. Perhaps the hardest task in the life of a Christian is to learn to let go and surrender one's will, understanding, intellect and material goods to God. We so much want to be in control of our own lives, although the irony of this is, that most of us acknowledge that when our lives are changed or redirected it has been due to an happening outside of our control.

As the English Church commemorated Lancelot Andrewes, one of our most saintly and scholarly bishops on Thursday the 25th, I would like to share with you this morning some of his teaching on living in faith.

Faith as taught by Andrewes is one of the theological virtues [the others are godliness, knowledge and charity] as compared to the moral virtues [prudence, temperance, fortitude, and justice]. Perhaps you may ask, why does he not include hope as a theological virtue as set out in 1Cor.13 ? The answer is very simple. Andrewes saw hope as synonymous with faith.

For this divine both the theological and moral virtues were necessary in the Christian life. He likened these to an eight part choir, all of which are needed to produce a fine musical rendition. Of these, faith is "the root and foundation of all," as it is "the first that leadeth the dance". Although faith is the first part, Andrewes stressed it is only a part; all the other virtues are needed in living the Christian life, and it must end with charity which is the bond of perfection. Faith must work as it did in Peter "till it come Love".

Just as these virtues provided a harmonious quality with their various eight parts, Andrewes saw them as balancing the eight parts to repentance which must precede them. Those eight parts included, an acknowledgement of one's sins and wretchedness, confession, contrition, weeping or as the Fathers termed it the Sacrament of lachrymae and a breaking of the heart. Then only is the soul ready to turn from sin and to turn to God - mentanioa. It is when the heart is truly broken in repentance that it is ready to receive God's gift of faith.

Faith then is a gift, bestowed on us by grace. In that sense Andrewes agreed with the Protestant reformers, but that was as far as he went. He always insisted that Christians had to work at their faith. "Men must not persuade themselves it is an easie matter to be a good Christian." We must not stand idle in the market place, other wise Christ will ask, "Why stand ye idle all day?" So it is not only a question of what has been done for us, but what is done by us. "We must not be like lumps of flesh, laying all upon Christ's sholdiers, [but] we must 'walk' forward" and "proceed from one degree of perfection to another all our life time, till the time of death, which is the beginning and accomplishment of our perfection."

Although he never agreed with the Roman Church's teaching that good works are meritorous in themselves, he nevertheless believed that without good works faith would not bring us to heaven, or in the words of James "show me your faith by thy works". Thus Andrewes insisted that it was simply no good "to say to a brother or sister that is naked and destitute of daily food, Depart in peace, warm your selves, fill your bellies; but the inward compassion must shew it self outwardly, by giving them those things which are needful to the body." And so he maintained that Christians should follow blessed Paul's advice, "to be perfect in all good works." "For by our works our faith is made perfect and faith without them is imperfect and stark dead."

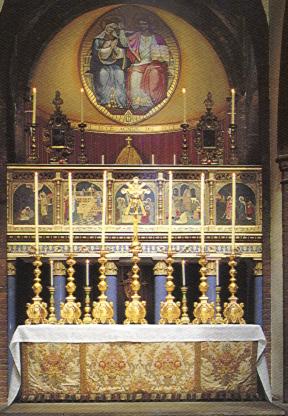

It is also faith that inspires us to labour more for the life to come which far outweighs all those pleasures and profits of this life. In other words we labour for the bread of life which endureth, rather than the bread for this life. Indeed it should make us hunger constantly for the eternal food. Of all Andrewes' teaching his most profound and persistent was eucharistic. For him it was hardly possible to be a Christian if one did not receive regularly the blessed Sacrament of His body and blood. It is only then we are so close to him that our faith will make us exclaim with Thomas, "my Lord and my God". The receiving of our Lord's life, Andrewes insisted, is the main way to know and trust in Christ who is the Author of our faith and who is the object of our faith. Nothing, he suggested, could make us more conscious of our blessed Saviour than the unfolding of the eucharistic drama.

One of the characteristics of Andrewes' preaching was to encourage his auditors to uses their senses as he saw these as instruments of faith, not only in creation but also at worship. Nowhere is this more applicable as when the Eucharist unfolds the passion, death and sacrifice of our blessed Saviour. Suggestions he made included our application of hearing, not only in listening to the readings, but when we come to the altar to receive the Cup, His Blood, for "'the remission of sins'" to hear the cry of our Saviour, from the cross: "Blood, ... also hath 'a voice,' specially innocent blood;" before Christ there was Abel's, blood "that cries loud in God's ears.'" Yet this is not as "loud as the blood whereof this 'cup of blessing' is 'the communion;' the voice of it will be heard above all, the cry of it will drown any cry else. And as it cries higher, so it differs in this, that it cries in a far other key." Unlike Abel's it cries "not for revenge, but for 'remission of sins;' for that, whereof it is itself the price and purchase, for our salvation in that 'great and terrible day of the Lord,' when nothing else will save us." So let us hear those "four syllables salvabitur."

Just as the sound of Christ's cry can draw us closer to Him, so can the visual. This holy Sacrament "proclaims Christ's death until He come again." By keeping His crucified body before our eyes, it is a reminder that in the Sacrament we are partakers "of his sufferings" and united to Him in those sufferings.

Andrewes also suggested that the senses of tasting and touching could also be experienced at the Eucharist in the context of eucharistic absolution. He explained that "in the liturgy of the ancient Church" these words "Behold this [coal] hath touch your lips, your iniquity shall be taken away, and your sinne purged" "are found applied to the blessed Sacrament of Christ's body and blood; for it is recorded by Basil, That at the celebration thereof, after the Sacrament was ministered to the people, the Priest stood up and said as the Seraphin doth here." That burning coal from the altar is now "Christ Jesus, who by the Sacrifice of his death which hee offered up to God, his Father, hath taken away our iniquities, and purged our sinnes". "The whole fruit of Religion is, the taking away of sinne" which cannot be had from hearing a sermon, nor from reading the scripture but only from tasting "of the bodily elements" of "bread and wine" and thus receiving "the body and blood of Christ, which is communicated unto us." And so in the Sacrament we "'taste of His goodness'" and forgiveness. Perhaps this morning you might like try to practice Andrewes' suggestions during the great Thanksgiving and Communion.

For Andrewes "the sign of true faith" in a Christian is that it strives to overcome "not only the Devil, but ... the pleasures, riches, [and] honors of the world." As Andrewes was a lover of souls, he frequently pleaded with his contemporaries to save their souls. One of his recommendations to fight Satan and to know our Saviour better was to "spend some time to make ourselves acquainted with ourselves and beg of God to reveal the secret evills of our nature unto us, to make us see, that treasure of iniquity, that hell of heart, that magazine of sin and selfishness that is there." He constantly told them that the faith of a Christian would always be tested by all kinds of affliction and temptations. Indeed our whole life is a continual warfare. After all Satan never let up on Christ, and therefore we should be on our guard against Satan's darts. A sure defence, he would say, was to be found in meditating upon the cross as it "teacheth all virtue". It is a "view" that we should contemplate "all our life long", and "blessed are the hours that are so spent!" As we gaze in silence on our blessed Lord we behold Him who has overcome all that this world tried to do to Him, whilst his outstretched arms are saying I am also embracing you as well as your sin. You are never alone. From me you can draw life and ease for your suffering. By simply allowing Christ's death to pierce our hearts, our hearts will respond to that love outpoured at Calvary, which will enrich our faith. If only we could do this, he assures us "we would adore that boundlesse mercy, that great victory, by which we are freed from this great evill, the dominion and tyranny of sin." We shall also discover that "the love of His cross is to us a pledge of the hope of His throne", the consummation of our faith.

And what of those who love this life more than the eternal? Such people he described as being "parasites" to others "for favour or gain", who "love to be flattered of others, and to have a great and glorious name for small and simple gifts, though our deeds be very small and few." They want "a long lasting life" here in order to enjoy carnal pleasures, but what good is a long life unless we seek that life "whose years shall never fail. Our body is corpus mortis and what is lavished on the body will perish with it." Yet if we trust in Christ He will lead us "to set our minds ... on things above ... where [He] is." And why there? Because, where He is, there are the things we seek for, and here cannot find. There 'He is sitting'; - so at rest. And 'at the right hand' - so in glory." This we also should "make our agendum."

So it is hardly surprising that one of Andrewes' constant teachings was the importance of the NOW. A true faith enables a Christian to live in the eternal now, conscious of trying to live in a state of grace, and so when we sin we seek God's forgiveness and from whomever we offend. Our faithfulness is really a constant circle of falling and rising, but persevering to the end by the grace of God.

As he preached in one of his Paschal sermons:

... it behoves us ... to look back upon our living unto Christ, that is, that we not only 'die to sin,' and 'live to God, but die and live as He did, that is, 'once for all;' which is an utter abandoning 'once' of sin's dominion, and a continual, constant, persisting in a good course 'once' begun. Sin's dominion, it languisheth sometimes in us, and falls happily into a swoon, but it dieth not quite 'once for all.' Grace lifteth up the eye, and looketh up a little, and giveth some sign of life, but never perfectly receiveth. O that once we might come to this! no more deaths, no more resurrections, but one! that we might once make an end of our daily continual [relapses] to which we are so subject, and once get past these pangs and qualms of godliness, this righteousness like the morning cloud, which is all we perform; that we might grow habituate in grace, 'rooted and founded in it; steady and never to be removed;' that we might enter into, and pass a good account of this our similiter et vos!

But as pilgrims, Andrewes knew this could never be attained this side of the grave, but he continually stressed that if we persevered to seek first the kingdom of God and trust completely in the blessed Trinity rather than our own resources then our faith would be at last perfected in the light of the beatific vision as the glorified Christ is the "Finisher of our faith."

Lord, increase my faith,

as a grain of mustard seed;

not dead,

enduring but for a time,

feigned,

masking void the law;

but a faith

working by love,

working with works,

a supplier of virtue.

living,

overcoming the world,

most holy. Amen.

.