NICHOLAS FERRAR AND LITTLE GIDDING

During the span of the reign of King Charles I in a little village in Huntingdonshire, not too far from Cambridge, lived a family, the Ferrar family. Here mother, sons and daughter, and grandchildren showed how to live the Gospel by prayer, fasting, almsgiving, forgiveness and love. Litte Gidding breathed a quasi-monastic life a century after the monastic life had expired in England under Cromwell and Henry VIII.

Shakespeare described Malcolm’s queen as “oft’ner on her knees than on her feet” (Mac. 4. 3. 110), and so the same could be set for Mary Ferrar. In many ways Mrs. Ferrar set the example for the family and neighbourhood. She was seventy years old when the family came to Little Gidding. Despite her age she arose at 5.00 daily, took care of home and chapel as well as her many works of charity and teaching the children the psalms. When the family arrived at Little Gidding the little church of St. John was derelict. It was she who helped Nicholas with its restoration, and afterwards she kept God’s house beautifully.

Shakespeare described Malcolm’s queen as “oft’ner on her knees than on her feet” (Mac. 4. 3. 110), and so the same could be set for Mary Ferrar. In many ways Mrs. Ferrar set the example for the family and neighbourhood. She was seventy years old when the family came to Little Gidding. Despite her age she arose at 5.00 daily, took care of home and chapel as well as her many works of charity and teaching the children the psalms. When the family arrived at Little Gidding the little church of St. John was derelict. It was she who helped Nicholas with its restoration, and afterwards she kept God’s house beautifully.

All the family had his/her allotted work besides praying. The two eldest children of Suzanna, Mary and Anna, committed themselves to lives of chastity. As their grandmother grew older, Mary especially resumed much of her responsibility. She ran the surgery and book-binding work and bound the first concordance presented to Charles I. The poet Richard Crashaw described Mary in her "friar's grey gown" as "the gentlest, kindest, most tender-hearted and liberal handed soul I think is to-day alive." John, Nicholas’ brother, who has been outshone by his brother, was probably more saintly as he had much more to endure from having married a very complaining woman, Bathsheba, who tried to make everyone’s life miserable. Maycock described John as "a great Churchman, a devoted Christian, a man whose faith and loyalty were never dimmed by the most terrible trials."

All the family had his/her allotted work besides praying. The two eldest children of Suzanna, Mary and Anna, committed themselves to lives of chastity. As their grandmother grew older, Mary especially resumed much of her responsibility. She ran the surgery and book-binding work and bound the first concordance presented to Charles I. The poet Richard Crashaw described Mary in her "friar's grey gown" as "the gentlest, kindest, most tender-hearted and liberal handed soul I think is to-day alive." John, Nicholas’ brother, who has been outshone by his brother, was probably more saintly as he had much more to endure from having married a very complaining woman, Bathsheba, who tried to make everyone’s life miserable. Maycock described John as "a great Churchman, a devoted Christian, a man whose faith and loyalty were never dimmed by the most terrible trials."

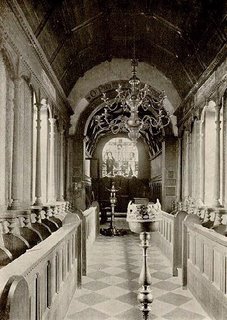

When Nicholas Ferrar and his mother undertook to beautify the family’s chapel at Little Gidding they were no doubt influenced by Bishop Lancelot Andrewes’ (d. 25th Sept., 1626) Episcopal chapel. As in the bishop’s chapel the altar stood on a raised platform to make it the focal point. There were two sets of furnishings for the chapel, one for the week and another for Sundays and holy days. For the week the colour was green, and so the altar was mainly covered in “green cloth, with suitable cushions and carpetts”. On Festival days, including Sundays the covering was of a “rich blue cloth, with cushions of the same, decorated with lace, and fring of silver” The altar was decked with magnificent silver plate: a paten, chalice and candlesticks with two large wax candles in them. Under the eastern window were four beautiful tablets of brass gilt displaying the Lord’s Prayer, the Ten Commandments, and the Apostles’ Creed. The pulpit was placed on the north side and the reading desk on the south, “and both on the same level” to show that preaching was not more important than prayer. There was a brass eagle-lectern for the bible and “the leg, laver and cover” of the font were also brass, “handsomely and expensively wrought and carved.” The lectern was placed next to the reading desk and the font by the pulpit. The whole chapel was wainscoted. Light for the daily services was provided by candles “set up in every part of the church, and on all the pillars of the stalls”. At the west end, a gallery was built for the organ.

It was in this chapel that life of the Ferrar family revolved. Probably the most telling example of their way of life is to examine both their Sunday and weekly routines devoted to prayer, work and recreation. The entire family rose very early every day of the week (in the summer at 4.00 and winter an hour later). On rising "the daughters and younger children gave God thanks for that night's preservation" after which they adjourned "into a large great chamber" (with a fire in winter) where Nicholas awaited them to lead their spiritual exercises of learning particular "Chapters and Psalms" off by heart each morning. They returned to their rooms and on Sundays to dress in their best attire for Sunday worship. When the bell rang at 9 o'clock they all assembled once again in "the great chamber” where a hymn was sung, accompanied by the organ, followed by everyone reciting "some sentence of Scripture before walking to the Church in two's". As they came into the church each made a “low obeisance” and took their various places in the church: “the Masters in the Chancel, and the boys kneeling upon the upper step" into the chancel whilst Mrs Ferrar and her daughter and all the women sat in the northern aisle and were always very reverent in their movements. Divine Service of Morning Prayer was led by Nicholas in his "surplice and hood", with all joining in the responses. When he had been ordained on Trinity Sunday, 1626 Nicholas had pledged, “I will also by the help of my God, set myself with more care and diligence than ever to serve our good Lord God, as is all our duties to do, in all we may.”

It was in this chapel that life of the Ferrar family revolved. Probably the most telling example of their way of life is to examine both their Sunday and weekly routines devoted to prayer, work and recreation. The entire family rose very early every day of the week (in the summer at 4.00 and winter an hour later). On rising "the daughters and younger children gave God thanks for that night's preservation" after which they adjourned "into a large great chamber" (with a fire in winter) where Nicholas awaited them to lead their spiritual exercises of learning particular "Chapters and Psalms" off by heart each morning. They returned to their rooms and on Sundays to dress in their best attire for Sunday worship. When the bell rang at 9 o'clock they all assembled once again in "the great chamber” where a hymn was sung, accompanied by the organ, followed by everyone reciting "some sentence of Scripture before walking to the Church in two's". As they came into the church each made a “low obeisance” and took their various places in the church: “the Masters in the Chancel, and the boys kneeling upon the upper step" into the chancel whilst Mrs Ferrar and her daughter and all the women sat in the northern aisle and were always very reverent in their movements. Divine Service of Morning Prayer was led by Nicholas in his "surplice and hood", with all joining in the responses. When he had been ordained on Trinity Sunday, 1626 Nicholas had pledged, “I will also by the help of my God, set myself with more care and diligence than ever to serve our good Lord God, as is all our duties to do, in all we may.”

Between Divine Service and the 10.30 service, the children of the near-by parishes came to recite the psalms they had learnt through the week. Their reward was a penny and Sunday dinner. The bell summoned all to church, including "the Psalm children" for the Second Service (anti-Communion) that was led by Nicholas from the altar followed by the sermon by "the Minister of Greater Gidding. On the first Sunday of each month the Holy Communion was celebrated and the family received Communion, as they did on all "great Festival times".

Between Divine Service and the 10.30 service, the children of the near-by parishes came to recite the psalms they had learnt through the week. Their reward was a penny and Sunday dinner. The bell summoned all to church, including "the Psalm children" for the Second Service (anti-Communion) that was led by Nicholas from the altar followed by the sermon by "the Minister of Greater Gidding. On the first Sunday of each month the Holy Communion was celebrated and the family received Communion, as they did on all "great Festival times".

When the worship was over, the "Psalm children" had their dinner first, after which they returned to their families. Before the family ate, they sung a hymn, accompanied by the organ, followed by grace. During dinner a chapter in the bible was read by "whose turn it was". After dinner ended, all were at liberty to do what they wished until the bell rang at 2.00 p.m. which summoned them "to Steeple Gidding church” to listen to another sermon. Back in the great Chamber they "said all those psalms that day at one time" after which they could please themselves until supper. Once again they sang before grace, and were read to during the meal. Once finished their time was their own until prayer time at 8. 00 p.m. Once prayers were finished, the young received Mrs. Ferrar's blessing before going to bed.

When the worship was over, the "Psalm children" had their dinner first, after which they returned to their families. Before the family ate, they sung a hymn, accompanied by the organ, followed by grace. During dinner a chapter in the bible was read by "whose turn it was". After dinner ended, all were at liberty to do what they wished until the bell rang at 2.00 p.m. which summoned them "to Steeple Gidding church” to listen to another sermon. Back in the great Chamber they "said all those psalms that day at one time" after which they could please themselves until supper. Once again they sang before grace, and were read to during the meal. Once finished their time was their own until prayer time at 8. 00 p.m. Once prayers were finished, the young received Mrs. Ferrar's blessing before going to bed.

One of the very important aspects of Sunday's routine was that worship was for everyone, including the servants. So that there could be "much freedom that day from bodily employment [Nicholas] ordered that what was for Dinner should be all performed with the least and speeediest loss of time ... and all the dinner to be set" in the oven “before Church time, and so all the Servants were ready to go to church."

One of the very important aspects of Sunday's routine was that worship was for everyone, including the servants. So that there could be "much freedom that day from bodily employment [Nicholas] ordered that what was for Dinner should be all performed with the least and speeediest loss of time ... and all the dinner to be set" in the oven “before Church time, and so all the Servants were ready to go to church."

If you came this way,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

Taking any route, starting from anywhere,

At any time or at any season You are here to kneel

Where prayer has been valid. And prayer is more

Where prayer has been valid. And prayer is more

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Than an order of words, the conscious occupation

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying.

Of the praying mind, or the sound of the voice praying.

- From Eliot's Little Gidding

The week routine began the same as Sundays until 6am when the hourly recitation of the appointed psalms and chapters of Scripture to be read on a roster basis began, and ended with the singing of a hymn. Before leaving the Great Chamber, the children recited their sentence of Scripture, and then walked with the rest to the church in the same fashion as on Sunday, and sat in the same places while Nicholas conducted the service. Returning to the house, the 7 o'clock psalms and chapter were said, concluding with the singing of this short hymn:

The week routine began the same as Sundays until 6am when the hourly recitation of the appointed psalms and chapters of Scripture to be read on a roster basis began, and ended with the singing of a hymn. Before leaving the Great Chamber, the children recited their sentence of Scripture, and then walked with the rest to the church in the same fashion as on Sunday, and sat in the same places while Nicholas conducted the service. Returning to the house, the 7 o'clock psalms and chapter were said, concluding with the singing of this short hymn:

Thus Angel sung, and so do we,

To God on high, all glory be,

Let him on earth his peace bestow,

And unto men his favour show.

Breakfast followed and afterwards the youth went to school. Over the years outside students also came for their education. Three schoolmasters taught respectively English and Latin, arithmetic and writing, and music. The last was very important in the life of Little Gidding as every member of the household participated. Nicholas also taught higher education, including modern languages in which he was proficient. Yet all was not all work and no play. All children were encouraged in such sports as running, vaulting and archery, to which Thursday and Saturday afternoons were devoted. The four older girls worked on the Concordance, embroidery, singing and playing their instruments, writing, ciphering and were instructed by their uncle in first-aid. Calligraphy and book-binding were also were also essential crafts taught, especially for the concordances. The very young were looked after by Mrs. Ferrar. After 10.00 a.m. Chapter, the Litany was said each day in the church. It certainly was a busy-bee household. No one was idle.

Breakfast followed and afterwards the youth went to school. Over the years outside students also came for their education. Three schoolmasters taught respectively English and Latin, arithmetic and writing, and music. The last was very important in the life of Little Gidding as every member of the household participated. Nicholas also taught higher education, including modern languages in which he was proficient. Yet all was not all work and no play. All children were encouraged in such sports as running, vaulting and archery, to which Thursday and Saturday afternoons were devoted. The four older girls worked on the Concordance, embroidery, singing and playing their instruments, writing, ciphering and were instructed by their uncle in first-aid. Calligraphy and book-binding were also were also essential crafts taught, especially for the concordances. The very young were looked after by Mrs. Ferrar. After 10.00 a.m. Chapter, the Litany was said each day in the church. It certainly was a busy-bee household. No one was idle.

When dinner was over each day, the members of the household continued their respective studies or work until 4.00 p.m. when it was time to go to Church for Evensong. The evenings were spent similar to Sundays: in Summer enjoying the outdoors, while in winter sitting around the fire while various members of the family read from various history, travel or exploration books. The day ended with 8.00 p.m. prayers except those whose turn it was to keep the vigil. The climax of prayer life of Little Gidding was the keeping of the all night vigils. The children kept the earlier hours until midnight and the early morning hours were kept usually by Nicholas.

When dinner was over each day, the members of the household continued their respective studies or work until 4.00 p.m. when it was time to go to Church for Evensong. The evenings were spent similar to Sundays: in Summer enjoying the outdoors, while in winter sitting around the fire while various members of the family read from various history, travel or exploration books. The day ended with 8.00 p.m. prayers except those whose turn it was to keep the vigil. The climax of prayer life of Little Gidding was the keeping of the all night vigils. The children kept the earlier hours until midnight and the early morning hours were kept usually by Nicholas.

One of the features of life at Little Gidding were the performances of The Little Academy that involved all the family, especially the children. "It is founded on the Feasted of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, with a sister named Mary as its chief, for the purpose of imitating those saints whose names its members bear, through the practice of mortification, devotion and the study of wisdom". It corresponded "with well-known stages of the mystical way: purgation, illumination, perfection" - the purgare, illuminare, perficere made popular by James I’s favourite preacher at Court, Lancelot Andrewes. At the meetings of the Academy allegorical stories were acted such as that of Pyrrhus. Afterwards members would speak in turn to open up discussion that sought for truth and wisdom. Ultimately all this leads to the Truth, Christ Himself. As well as encouraging Christian thinking The Little Academy enabled a freedom of thought and ideas in those not so old - a wonderful medium of education. It is said that Charles I visited Little Gidding for such a performance.

One of the features of life at Little Gidding were the performances of The Little Academy that involved all the family, especially the children. "It is founded on the Feasted of the Purification of the Blessed Virgin Mary, with a sister named Mary as its chief, for the purpose of imitating those saints whose names its members bear, through the practice of mortification, devotion and the study of wisdom". It corresponded "with well-known stages of the mystical way: purgation, illumination, perfection" - the purgare, illuminare, perficere made popular by James I’s favourite preacher at Court, Lancelot Andrewes. At the meetings of the Academy allegorical stories were acted such as that of Pyrrhus. Afterwards members would speak in turn to open up discussion that sought for truth and wisdom. Ultimately all this leads to the Truth, Christ Himself. As well as encouraging Christian thinking The Little Academy enabled a freedom of thought and ideas in those not so old - a wonderful medium of education. It is said that Charles I visited Little Gidding for such a performance.

Another characteristic works of Little Gidding was the compiling of concordances which the children under supervision worked on in a room specially allotted to the purpose. These were a cut and paste of the four gospels in order to have “one continuous story”. Alongside this was also compiled Harmonies by indicating each of the four gospels with the use of a respective letter: A, B, C, D. These allowed each Gospel to be read continuously if desired. So in essence there were two types of biblical narratives – one enabled to read parts from the different gospels; the other by reading from one set of letters, one gospel with its own teaching of our Lord could be read in its entirety. Apart from the Gospels the children also produced similar concordances for the Books of Kings and Chronicles, The Five Books of Moses and The Acts of the Apostles. The first book was completed in 1630 and quickly came to the attention of the king who commanded that the volume on the Books of Kings and Chronicles should be compiled for him. He also requested other volumes as did the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York and other nobility. Eleven books compiled at Little Gidding have survived of which seven are of the four Gospels, one of the Books of Kings and Chronicles, two of the Five Books of Moses and one of the Acts of the Apostles.

Another characteristic works of Little Gidding was the compiling of concordances which the children under supervision worked on in a room specially allotted to the purpose. These were a cut and paste of the four gospels in order to have “one continuous story”. Alongside this was also compiled Harmonies by indicating each of the four gospels with the use of a respective letter: A, B, C, D. These allowed each Gospel to be read continuously if desired. So in essence there were two types of biblical narratives – one enabled to read parts from the different gospels; the other by reading from one set of letters, one gospel with its own teaching of our Lord could be read in its entirety. Apart from the Gospels the children also produced similar concordances for the Books of Kings and Chronicles, The Five Books of Moses and The Acts of the Apostles. The first book was completed in 1630 and quickly came to the attention of the king who commanded that the volume on the Books of Kings and Chronicles should be compiled for him. He also requested other volumes as did the Prince of Wales, the Duke of York and other nobility. Eleven books compiled at Little Gidding have survived of which seven are of the four Gospels, one of the Books of Kings and Chronicles, two of the Five Books of Moses and one of the Acts of the Apostles.

Little Gidding became well known in the 1630’s and was dubbed The Arminian Nunnery by the Puritan, William Prynne. Nevertheless it enjoyed many visitors who were drawn to this little community’s life style. Amongst them was the poet, Richard Crashaw, a fellow at Peterhouse who helped John Cosin in beautifying its chapel, probably not a more beautiful chapel elsewhere in Cambridge in the 1630’s. The poet found himself drawn to this place of prayer, and he most probably took part in the night vigil when he was present. He was particularly attracted to Mary Collett who had vowed to live a life of virginity, and who on her grandmother’s death took her place as Mother of the community. Despite their age difference (he was nineteen, she thirty-two when they first met) a spiritual bond deepened between them. The bishop of Lincoln, Dr. Williams, was also a regular guest. Charles I too paid a visit on his way to Scotland in 1633. The Ferrar family met him at a field, which ever since has been known as The King’s Close, and then processed to the church for prayer.

Not long afterwards Mrs. Ferrar died in 1634, and three years later Nicholas also departed this life. These two deaths so close together bereaved the community of much guidance. Nevertheless John with Mary did their best to maintain the spirit of Little Gidding. The approaching Civil War and the ascendancy of the Puritans who had no appreciation of beauty and asceticism in all its form made life difficult to the say the least and they were forced to leave. The family returned in 1647 and until his death

Not long afterwards Mrs. Ferrar died in 1634, and three years later Nicholas also departed this life. These two deaths so close together bereaved the community of much guidance. Nevertheless John with Mary did their best to maintain the spirit of Little Gidding. The approaching Civil War and the ascendancy of the Puritans who had no appreciation of beauty and asceticism in all its form made life difficult to the say the least and they were forced to leave. The family returned in 1647 and until his death

in 1657 John tried to keep the family together and he continued the monthly commemoration begun by his brother.

We come O Lord most mighty God and merciful Father to offer unto you thy divine majesty the monthly tribute of that duty which we are bound continually to perform the tender of most humble and hearty thanks and praises for those infinite and inestimable benefits which we most unworthy sinners have in such abundant manner from time to time received of thy goodness, and do even still unto this hour enjoy. Amen.

We come O Lord most mighty God and merciful Father to offer unto you thy divine majesty the monthly tribute of that duty which we are bound continually to perform the tender of most humble and hearty thanks and praises for those infinite and inestimable benefits which we most unworthy sinners have in such abundant manner from time to time received of thy goodness, and do even still unto this hour enjoy. Amen.

Yet the character of Little Gidding has become “suspended in time”.

Yet the character of Little Gidding has become “suspended in time”.

What they had to leave us – a symbol:

What they had to leave us – a symbol:

A symbol perfected in death.

A symbol perfected in death.

And all shall be well and

And all shall be well and

All manner of thing shall be well

All manner of thing shall be well

By the purification of the motive

By the purification of the motive

In the ground of our beseeching. Eliot

In the ground of our beseeching. Eliot