The Sibyl of the Rhine, Hildegard of Bingen (1098-1179)

(Sibyl is a prophetess of which in ancient times the most famous was Pythia of Delphi).

Hildegard, Abbess of Bingen was one of the most articulated and accomplished women of the Middle Ages, indeed of both sexes. Born in the age of Peter Abelard and Bernard of Clairvaux, Eleanor of Aquitaine and the rise of universities in Europe, such as that in Paris and Oxford, she made her own contribution to learning, music, science and art. She founded monasteries, travelled widely and advised popes, bishops and rulers in times of schisms. Over a hundred letters exist of hers to emperors, popes, bishops, nobilities and of course nuns. She described herself as a ‘feather on the breath of God’. As she wrote:

Listen: there was once a king sitting on his throne. Around Him stood great and wonderfully beautiful columns ornamented with ivory, bearing the banners of the king with great honour. Then it pleased the king to raise a small feather from the ground, and he commanded it to fly. The feather flew, not because of anything in itself but because the air bore it along. Thus am I, a feather on the breath of God.

As the tenth child in a noble family she was dedicated to the church. When she was eight years old Hildegard was sent to the anchoress, Jutta, for her religious education. Her anchorage, attached to the church, was near the Benedictine monastery at Disibodenberg. Here Hildegard would have learnt the basics and the rudiments of Latin, that included learning the Psalms (these formed the basis of The Monastic Hours). Perhaps the music she heard in the adjacent church stirred her own musical gifts.

When Jutta died, Hildegard succeeded her at the anchorage convent, at the age of thirty-eight. During those thirty years of being with Jutta, Hildegard began having her visions. Of these she only confided to Jutta and Volmar who would become her lifelong secretary. One such vision enabled her to understand religious texts that changed her life. She was commanded to write down her visions. Perhaps her best known work is Scivias, (know the way of the Lord) which had the papal imprimatur (Eugenius III). With the publication of this she soon became known across Germanic lands and soon further afield.

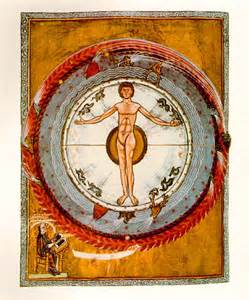

She left us about seventy poems and nine books. She wrote a commentary on the Gospels and another on the Athanasian Creed. Apart from Scivias she also wrote Liber vitae meritorum (1150-63) (Book of Life's Merits) and Liber divinorum operum(1163) ("Book of Divine Works"), in which she set forth her theology of microcosm and macrocosm, that is, man being a reflection or mirror of God's creation. She also wrote on natural history and curative powers in Liber subtilatum ("The book of subtleties of the Diverse Nature of Things").

In her theological writings she explained the Trinity like this:

Then I saw a bright light, and in this bright light the figure of a man the colour of a sapphire, which was all blazing with gentle glowing fire. And that bright light bathed the whole of the glowing fire, and the glowing fire bathed the bright light; and the glowing fire poured over the whole human figure, so that the three were one light in one power of potential. And again I heard the living Light say to me: "This is the perception of God's mysteries. . . .

Therefore you see a bright light, which without any flaw of illusion deficiency or deception designates the Father; and in this light the figure of a man the colour of sapphire, which without any flaw of obstinacy, envy or iniquity designates the Son, Who was begotten of the Father in Divinity before time began, and then within time was incarnate in the world in Humanity; which is all blazing with a gentle glowing fire, which fire without any flaw of aridity, mortality or darkness designates the Holy Spirit, by Whom the Only-begotten of God was conceived in the flesh and born of the Virgin within time and poured the true light into the world. And that bright light bathes the whole of the glowing fire, and the glowing fire bathes the bright light: and the bright light and the glowing fire pour over the whole human figure so that the three are one light in one power of potential.

When writing about the first Pentecost she explained:.

And the Holy Spirit took their human fear from them, so that no dread was in them, and they would never fear human savagery when they spoke the word of God; all such timidity was taken from them, so ardently and so quickly that they became firm and not soft, and dead to all adversity that could befall them. And then they remembered with perfect understanding all the things they had heard and received from Christ with sluggish faith and comprehension; they recalled them to memory as if they had learned them from Him in that very hour.

She also wrote extensively on social justice, caring for the down-trodden and the poor, and of the duty of us to see each other as created in the image of God.

Her scientific views were derived from the ancient Greek cosmology of the four elements-fire, air, water, and earth-with their complementary qualities of heat, dryness, moisture, and cold, and the corresponding four humours in the body-choler (yellow bile), blood, phlegm, and melancholy (black bile). Human constitutionwas based on the preponderance of one or two of the humours.

She was also an artist and drew diagrams for her books. Indeed writings bring science, art, and religion together. She is deeply involved in all three, and looks to each for insights that will enrich her understanding of the others.

One of her legacies is her music. In the twelfth century there was nothing quite like Hildegard’s compositions. What has survived are seventy-two chants including a play, Ordo Virtutum set to music. Her music reflected the kind of person she was – a love of the beautiful and the exquisite in all things. For her music provided that harmony between earth and heaven and was extremely important to her. There must be harmony between voices and instruments. Thus in singing and playing music, we integrate mind, heart and body, and heal discord between us. Hildegard combined all her music into a cycle called "The Symphony of the Harmony of the Heavenly Revelations."

Most of her music was written for the Divine Offices, of which the largest were the Antiphons, next were the Responses, and Sequences as well as hymns and to suit the female voice. These were sung in her own chapel. Here her music soared to heaven joyfully as her nuns sang and sang their praises. Their singing reflected their attire. Not for Hildegard to have her nuns decked out in sombre clothing. Rather her nuns dressed in silk of bright colours – reds- yellows – green. To match their fine gowns they wore enamelled crowns painted like jewels. What a beautiful and uplifting experience it must have been to be present in that Bingen chapel in the twelfth century as Hildegard’s nun made melody in their hearts for the Lord eight times a day.

About 1150 she moved the convent to Bingen, about thirty miles upstream on the Rhine. From here she travelled extensively to preach and start sister houses. These travels took her as far afield as Paris and Switzerland as well as Southern Germany. She tried to have her ideas taught at the university of Paris.

One incident towards the end of her life, now in her eighties, sums her up her life superbly. Even though she knew the consequences, she allowed a nobleman who had been ex-communicated to receive the last rites and be buried in the convent’s grounds. She believed this was God’s will but church authorities thought differently, and she and her community were ex-communicated. She accepted this knowing in time it would be lifted. And so it was. After all she had long disputed with popes, bishops and kings, and this was a mere hiccup.

Hildegard wanted God’s children to be happy and enjoy life. As she wrote:

He indeed wants us to enjoy life.

Glance at the sun.

See the moon and the stars.

Gaze at the beauty of earth's greenings.

Now, think.

What God gives to humankind

with all these things.

For Hildegard God’s creation was simply magnificent and she was part of it:

The fire has its flame and praises God.

The wind blows the flame and praises God.

In the voice we hear the word which praises God.

And the word, when heard, praises God.

So all of creation is a song of praise to God.

At last in 2012 she was finally recognised and canonised and along with Teresa of Avila and Catherine of Siena was proclaimed as doctor of the church.

ST. HILDEGARD, DOCTOR, MYSTIC, ABBESS,

COMPOSER AND WRITER