This rare beautiful spirit also had a rather malicious mother-in-law, but Monnica gradually "won the older woman over by her dutiful attentions and her constant patience and gentleness." Monnica's perseverance, that queen of virtues, along with her prayers eventually won her husband as a convert, and he was baptized a year before he died. 'After his conversion she no longer had to grieve over those faults which had tried her patience.' What joy it was for Monnica to know that her husband tasted and saw how good the Lord is, before he died (IX. 9).

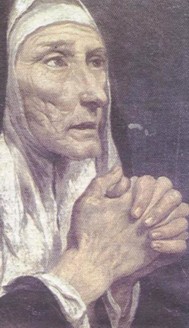

And what of Monnica as a mother? No son has sung his Mother's praises louder than St. Augustine, and one cannot read his Confessions without being deeply moved as he tells of his conversion through his Mother's prayers and grace. As he commented in this remarkable piece of literature he had omitted much as he was 'pressed for time' 'but I will omit not a word that my mind can bring to birth concerning your servant, my mother.' 'In the flesh she brought me birth in this world: in her heart she brought me birth in your eternal light." She served us not only as a mother but also as if she were a daughter to us. She had recognized Augustine's talent as a leader and thinker and encouraged him in his education. She had also enrolled him as a catechumen in preparation for baptism, but he scornfully rejected this and he turned to other philosophies instead. But she bore his arrogance and scorn with the same patience as she had her husband's temper and faithlessness. Above all she prayed unceasingly for her son's conversion who related that in his time of adolescent depravity God "rescued my soul from the depth of this darkness because my mother, your faithful servant, wept for me, shedding more tears for my spiritual death than other mothers shed for the bodily death of a son. For in her faith and in the spirit which she had from you she looked on me as dead. You heard her and did not despise the tears which streamed down and watered the earth in every place where she bowed her head in prayer."

And what of Monnica as a mother? No son has sung his Mother's praises louder than St. Augustine, and one cannot read his Confessions without being deeply moved as he tells of his conversion through his Mother's prayers and grace. As he commented in this remarkable piece of literature he had omitted much as he was 'pressed for time' 'but I will omit not a word that my mind can bring to birth concerning your servant, my mother.' 'In the flesh she brought me birth in this world: in her heart she brought me birth in your eternal light." She served us not only as a mother but also as if she were a daughter to us. She had recognized Augustine's talent as a leader and thinker and encouraged him in his education. She had also enrolled him as a catechumen in preparation for baptism, but he scornfully rejected this and he turned to other philosophies instead. But she bore his arrogance and scorn with the same patience as she had her husband's temper and faithlessness. Above all she prayed unceasingly for her son's conversion who related that in his time of adolescent depravity God "rescued my soul from the depth of this darkness because my mother, your faithful servant, wept for me, shedding more tears for my spiritual death than other mothers shed for the bodily death of a son. For in her faith and in the spirit which she had from you she looked on me as dead. You heard her and did not despise the tears which streamed down and watered the earth in every place where she bowed her head in prayer."

Monnica was with Augustine in Milan when he was baptised at the Easter Vigil in 387 by Ambrose. After his baptism and shortly before her death she was full of praise for her son.

Monnica was with Augustine in Milan when he was baptised at the Easter Vigil in 387 by Ambrose. After his baptism and shortly before her death she was full of praise for her son.

I was full of joy indeed in her testimony, when, in that her last illness, flattering my dutifulness, she called me "kind," and recalled, with great affection of love, that she had never heard any harsh or reproachful sound come out of my mouth against her. But yet, O my God, who madest us, how can the honour which I paid to her be compared with her slavery for me? As, then, I was left destitute of so great comfort in her, my soul was stricken, and that life torn apart as it were, which, of hers and mine together, had been made but one (IX.12).

After the Baptism Monnica, Augustine and his younger brother and his son journeyed to Ostia in preparation to return home in North Africa. Having accomplished her task in life as they awaited ship mother and son shared a most spiritual moving conversation Augustine explained:

After the Baptism Monnica, Augustine and his younger brother and his son journeyed to Ostia in preparation to return home in North Africa. Having accomplished her task in life as they awaited ship mother and son shared a most spiritual moving conversation Augustine explained:

As the day now approached on which she was to depart this life (which day Thou knewest, we did not), it fell out-Thou, as I believe, by Thy secret ways arranging it-that she and I stood alone, leaning in a certain window, from which the garden of the house we occupied at Ostia could be seen; at which place, removed from the crowd, we were resting ourselves for the voyage, after the fatigues of a long journey. We then were conversing alone very pleasantly; and, 'forgetting those things which are behind, and reaching forth unto those things which are before,' we were seeking between ourselves in the presence of the Truth, which Thou art, of what nature the eternal life of the saints would be, which eye hath not seen, nor ear heard, neither hath entered into the heart of man. But yet we opened wide the mouth of our heart, after those supernal streams of Thy fountain, 'the fountain of life,' which is 'with Thee;' that being sprinkled with it according to our capacity, we might in some measure weigh so high a mystery.

And when our conversation had arrived at that point, that the very highest pleasure of the carnal senses, and that in the very brightest material light, seemed by reason of the sweetness of that life not only not worthy of comparison, but not even of mention, we, lifting ourselves with a more ardent affection towards 'the Selfsame,' did gradually pass through all corporeal things, and even the heaven itself, whence sun, and moon, and stars shine upon the earth; tea, we soared higher yet by inward musing, and discoursing, and admiring Thy works; and we came to our own minds, and went beyond them, that we might advance as high as that region of unfailing plenty, where Thou feedest Israel for ever with the food of truth, and where life is that Wisdom by whom all these things are made, both which have been, and which are to come; and she is not made, but is as she hath been, and so shall ever be; yea, rather, to 'have been,' and 'to be hereafter,' are not in her, but only 'to be,' seeing she is eternal, for to 'have been' and 'to be hereafter' are not eternal. And while we were thus speaking, and straining after her, we slightly touched her with the whole effort of our heart; and we sighed, and there left bound 'the first-fruits of the Spirit;' and returned to the noise of our own mouth, where the word uttered has both beginning and end. And what is like unto Thy Word, our Lord, who remaineth in Himself without becoming old, and 'maketh all things new?'

We were saying, then, If to any man the tumult of the flesh were silenced,-silenced the phantasies of earth, waters, and air,-silenced, too, the poles; yea, the very soul be silenced to herself, and go beyond herself by not thinking of herself,-silenced fancies and imaginary revelations, every tongue, and every sign, and whatsoever exists by passing away, since, if any could hearken, all these say, 'We created not ourselves, but were created by Him who abideth for ever:' If, having uttered this, they now should be silenced, having only quickened our ears to Him who created them, and He alone speak not by them, but by Himself, that we may hear His word, not by fleshly tongue, nor angelic voice, nor sound of thunder, nor the obscurity of a similitude, but might hear Him-Him whom in these we love-without these, like as we two now strained ourselves, and with rapid thought touched on that Eternal Wisdom which remaineth over all. If this could be sustained, and other visions of a far different kind be withdrawn, and this one ravish, and absorb, and envelope its beholder amid these inward joys, so that his life might be eternally like that one moment of knowledge which we now sighed after, were not this 'Enter thou into the joy of Thy Lord?' And when shall that be? When we shall all rise again; but all shall not be changed (IX.10).

We were saying, then, If to any man the tumult of the flesh were silenced,-silenced the phantasies of earth, waters, and air,-silenced, too, the poles; yea, the very soul be silenced to herself, and go beyond herself by not thinking of herself,-silenced fancies and imaginary revelations, every tongue, and every sign, and whatsoever exists by passing away, since, if any could hearken, all these say, 'We created not ourselves, but were created by Him who abideth for ever:' If, having uttered this, they now should be silenced, having only quickened our ears to Him who created them, and He alone speak not by them, but by Himself, that we may hear His word, not by fleshly tongue, nor angelic voice, nor sound of thunder, nor the obscurity of a similitude, but might hear Him-Him whom in these we love-without these, like as we two now strained ourselves, and with rapid thought touched on that Eternal Wisdom which remaineth over all. If this could be sustained, and other visions of a far different kind be withdrawn, and this one ravish, and absorb, and envelope its beholder amid these inward joys, so that his life might be eternally like that one moment of knowledge which we now sighed after, were not this 'Enter thou into the joy of Thy Lord?' And when shall that be? When we shall all rise again; but all shall not be changed (IX.10).

Having seen her son baptised, Monnica had achieved her goal and therefore awaited death impatiently. As death approached, although it had been her wish to be buried beside her husband she said, "Lay this body anywhere, let not the care for it trouble you at all. This only I ask, that you will remember me at the Lord's altar, wherever you be." As Augustine expressed it:

But, as I reflected on Thy gifts, O thou invisible God, which Thou instillest into the hearts of Thy faithful ones, whence such marvellous fruits do spring, I did rejoice and give thanks unto Thee, calling to mind what I knew before, how she had ever burned with anxiety respecting her burial-place, which she had provided and prepared for herself by the body of her husband. For as they had lived very peacefully together, her desire had also been (so little is the human mind capable of grasping things divine) that this should be added to that happiness, and be talked of among men, that after her wandering beyond the sea, it had been granted her that they both, so united on earth, should lie in the same grave. But when this uselessness had, through the bounty of Thy goodness, begun to be no longer in her heart, I knew not, and I was full of joy admiring what she had thus disclosed to me; though indeed in that our conversation in the window also, when she said, "What do I here any longer?" she appeared not to desire to die in her own country. I heard afterwards, too, that at the time we were at Ostia, with a maternal confidence she one day, when I was absent, was speaking with certain of my friends on the contemning of this life, and the blessing of death; and when they-amazed at the courage which Thou hadst given to her, a woman-asked her whether she did not dread leaving her body at such a distance from her own city, she replied, 'Nothing is far to God; nor need I fear lest He should be ignorant at the end of the world of the place whence He is to raise me up.'

"On the ninth day, then, of her sickness, the fifty-sixth year of her age, and the thirty-third of mine, was that religious and devout soul set free from the body." Augustine described her death with great feeling.

I closed her eyes; and there flowed a great sadness into my heart, and it was passing into tears, when mine eyes at the same time, by the violent control of my mind, sucked back the fountain dry, and woe was me in such a struggle! But, as soon as she breathed her last the boy Adeodatus burst out into wailing, but, being checked by us all, he became quiet. In like manner also my own childish feeling, which was, through the youthful voice of my heart, finding escape in tears, was restrained and silenced. For we did not consider it fitting to celebrate that funeral with tearful plaints and groanings; for on such wise are they who die unhappy, or are altogether dead, wont to be mourned. But she neither died unhappy, nor did she altogether die. For of this were we assured by the witness of her good conversation her 'faith unfeigned,' and other sufficient grounds (IX.11-2).

Augustine also expressed how he held back his tears and grief during her funeral. "I did not weep even during the prayers [although] I was secretly weighed down with grief." Afterwards when his grief gave way, he pours out of his soul.

But,-my heart being now healed of that wound, in so far as it could be convicted of a carnal affection,-I pour out unto Thee, O our God, on behalf of that Thine handmaid, tears of a far different sort, even that which flows from a spirit broken by the thoughts of the dangers of every soul that dieth in Adam. And although she, having been 'made alive' in Christ even before she was freed from the flesh had so lived as to praise Thy name both by her faith and conversation, yet dare I not say that from the time Thou didst regenerate her by baptism, no word went forth from her mouth against Thy precepts. And it hath been declared by Thy Son, the Truth, that 'Whosoever shall say to his brother, Thou fool, shall be in danger of hell fire.' And woe even unto the praiseworthy life of man, if, putting away mercy, Thou shouldest investigate it. But because Thou dost not narrowly inquire after sins, we hope with confidence to find some place of indulgence with Thee. But whosoever recounts his true merits to Thee, what is it that he recounts to Thee but Thine own gifts? Oh, if men would know themselves to be men; and that 'he that glorieth' would 'glory in the Lord!'

I then, O my Praise and my Life, Thou God of my heart, putting aside for a little her good deeds, for which I joyfully give thanks to Thee, do now beseech Thee for the sins of my mother. Hearken unto me, through that Medicine Of our wounds who hung upon the tree, and who, sitting at Thy right hand, 'maketh intercession for us.' I know that she acted mercifully, and from the heart forgave her debtors their debts; do Thou also forgive her debts, whatever she contracted during so many years since the water of salvation. Forgive her, O Lord, forgive her, I beseech Thee; 'enter not into judgment' with her. Let Thy mercy be exalted above Thy justice, because Thy words are true, and Thou hast promised mercy unto 'the merciful;' which Thou gavest them to be who wilt 'have mercy' on whom Thou wilt 'have mercy,' and wilt 'have compassion' on whom Thou hast had compassion.

May she therefore rest in peace with her husband, whom she obeyed, with patience bringing forth fruit unto Thee, that she might gain him also for Thee. And inspire, O my Lord my God, inspire Thy servants my brethren, Thy sons my masters, who with voice and heart and writings I serve, that so many of them as shall read these confessions may at Thy altar remember Monica, Thy handmaid, together with Patricius, her sometime husband, by whose flesh Thou introducedst me into this life. May my mother's last entreaty to me be granted in the prayers of the many who read my confessions more than through my prayers alone (IX. 13).

Monnica's patience and perseverance has been a model for many, many mothers since as they pray for their sons to love Christ with all their hearts and souls and to be faithful to Him in all things

Monnica's patience and perseverance has been a model for many, many mothers since as they pray for their sons to love Christ with all their hearts and souls and to be faithful to Him in all things