As we are still promoting the Pauline Year my presentation this afternoon will be on Paul and as we are promoting also the monastic tradition today it will be based on what this apostle shared with his early converts on prayer and for us a couple of thousand years later.

The founder of the Carthusians, St. Bruno, was a scholar and teacher who after many years of teaching in Rheims, sought silence and solitude to be with his God in a desolate mountainous region near Greenoble, what we know as Chartreuse. The great apostle Paul also sought the same God but with a different background and direction but yet discovered too the risen Lord in solitude and silence.

The founder of the Carthusians, St. Bruno, was a scholar and teacher who after many years of teaching in Rheims, sought silence and solitude to be with his God in a desolate mountainous region near Greenoble, what we know as Chartreuse. The great apostle Paul also sought the same God but with a different background and direction but yet discovered too the risen Lord in solitude and silence.

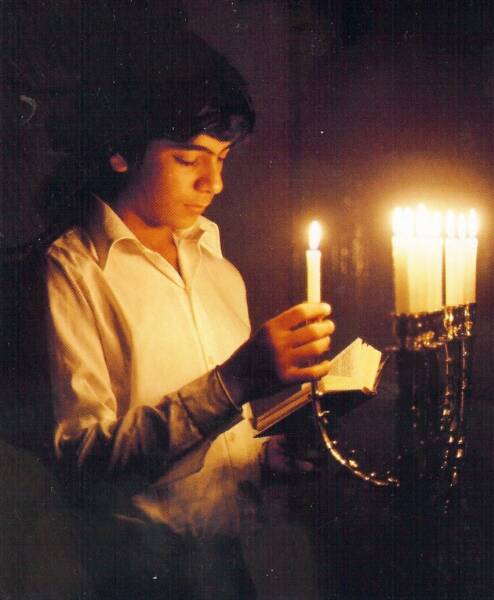

The first thing however we must remember about Paul is that he was a Jew and he never forsook that. As such he learnt to pray as soon as he was able to speak and to see its importance and regularity in his daily routine of life.

The first thing however we must remember about Paul is that he was a Jew and he never forsook that. As such he learnt to pray as soon as he was able to speak and to see its importance and regularity in his daily routine of life.

The second is Paul’s desert experience after his encounter with the Lord on the road to Damascus. That long experience would have shaped the rest of Paul’s life and just as St. Bruno, and indeed our Lord resorted to lonely spots to communicate with His Father, so did Paul. Abba, was the way a Jew addressed God in prayer. When our Lord taught His disciples to pray, especially in the Lucan version, which probably reflects the more authentic, it is very simple. Paul too alludes to its simplicity. Like Jesus he prayed “Abba” and invited his fellow Christians later on to do likewise as through baptism they were now adopted children of God. So he had this advice, withdraw and speak to your Father. The Spirit will guide you in what you will speak (Rom. 8.15). And so in his writings Paul referred to God in that language he knew from childhood, Abba. e.g. In Galatians he informed the early Christians that God has sent His Spirit into their hearts by crying Abba, Father (4. 6).

The second is Paul’s desert experience after his encounter with the Lord on the road to Damascus. That long experience would have shaped the rest of Paul’s life and just as St. Bruno, and indeed our Lord resorted to lonely spots to communicate with His Father, so did Paul. Abba, was the way a Jew addressed God in prayer. When our Lord taught His disciples to pray, especially in the Lucan version, which probably reflects the more authentic, it is very simple. Paul too alludes to its simplicity. Like Jesus he prayed “Abba” and invited his fellow Christians later on to do likewise as through baptism they were now adopted children of God. So he had this advice, withdraw and speak to your Father. The Spirit will guide you in what you will speak (Rom. 8.15). And so in his writings Paul referred to God in that language he knew from childhood, Abba. e.g. In Galatians he informed the early Christians that God has sent His Spirit into their hearts by crying Abba, Father (4. 6).

Out in the desert, calling upon Abba Paul sought him. My Father what do you want me to learn? What more will you reveal to me about your Son? Teach me the language I need now to witness for You and for Your Son. In the words of Isaiah, “Let all this blossom like a rose” ( Isaiah 35.1).

Out in the desert, calling upon Abba Paul sought him. My Father what do you want me to learn? What more will you reveal to me about your Son? Teach me the language I need now to witness for You and for Your Son. In the words of Isaiah, “Let all this blossom like a rose” ( Isaiah 35.1).

That Paul did discover the way of the Lord and to the Lord is all so evident in the letters he sent to the various Christian communities throughout Asia Minor and Greece, and thank God many have survived to this day. Whatever transpired out in the solace of the sand, Paul taught the fledgling Christians and us more about prayer than any other writer of the New Testament. So as we read his very old letters to-day what would Paul want us to understand about prayer and praying?

That Paul did discover the way of the Lord and to the Lord is all so evident in the letters he sent to the various Christian communities throughout Asia Minor and Greece, and thank God many have survived to this day. Whatever transpired out in the solace of the sand, Paul taught the fledgling Christians and us more about prayer than any other writer of the New Testament. So as we read his very old letters to-day what would Paul want us to understand about prayer and praying?

The first that I think Paul would want us to understand is that prayer is a gift – a gift of the Holy Spirit. It is the Spirit who prays within us. Paul would know only too well from his own life that it is “the Spirit [that] helps us in our weakness, for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words” (Rom. 8. 26). As Andrewes would say centuries later, if we find ourselves not being able to pray, we must humbly ask for grace to be able to pray. After all it is only prayer that keeps us from sin.

The first that I think Paul would want us to understand is that prayer is a gift – a gift of the Holy Spirit. It is the Spirit who prays within us. Paul would know only too well from his own life that it is “the Spirit [that] helps us in our weakness, for we do not know how to pray as we ought, but that very Spirit intercedes with sighs too deep for words” (Rom. 8. 26). As Andrewes would say centuries later, if we find ourselves not being able to pray, we must humbly ask for grace to be able to pray. After all it is only prayer that keeps us from sin.

We may sometimes think it is we who are praying, but if it is effective praying it will be from the Spirit that prods within. So perhaps if our prayers do not seem to be answered we should first examine the praying. Or sometimes we find ourselves in tune with prayer but we falter; we cannot find the right word to express what we want the Father to hear. It is at those times we should call to mind Paul’s encouraging words that the Spirit groans within us, reaching out and articulating what our intentions are. We just have to be patient. As Paul conveyed to Christians in Rome, “Rejoice in hope, be patient in suffering, persevere in prayer” (Rom. 12.12).

All kinds of prayer come from the Spirit.

What kind of prayer do we find in Paul’s letters?

Firstly, to rejoice and be happy that as Christians we know the Lord. “Rejoice in the Lord always and again I say rejoice.” Those words to the Philippians were at the heart of Paul’s understanding of prayer, and because they are such wonderful words they have been set to music by composers such as Purcell. Even in suffering and sorrow he was able to rejoice. When we but stop and think of Paul’s main teaching that in Christ’s death and resurrection we have been saved, justified, made righteous and have been promised eternal life, why would not the heart of our prayer life be one of rejoicing. But is it?

Firstly, to rejoice and be happy that as Christians we know the Lord. “Rejoice in the Lord always and again I say rejoice.” Those words to the Philippians were at the heart of Paul’s understanding of prayer, and because they are such wonderful words they have been set to music by composers such as Purcell. Even in suffering and sorrow he was able to rejoice. When we but stop and think of Paul’s main teaching that in Christ’s death and resurrection we have been saved, justified, made righteous and have been promised eternal life, why would not the heart of our prayer life be one of rejoicing. But is it?

In pondering on this aspect of our prayer life I recalled in the early 1990’s attending the Paschal Vigil Mass at St. Mary Mag’s in Oxford. Afterwards the vicar and I walked the short distance to the Orthodox Church, which was celebrating Easter at the same time as the Western Church that year. What a difference! What a contrast! We both had been participating in a Liturgy that should have expressed the most rejoicing time of the whole Christian year, but did we feel it, really feel it? No. We had to go to the Orthodox Church to experience the unleashing of what joy really meant. It simply bubbled over in every movement, in every greeting and in the celebration of the Liturgy. That experienced taught me what Paul meant “to rejoice in the Lord.” Perhaps if we kept as severe a Lent as the committed Orthodox does then it might induce us to be more joyous at the celebration of the Resurrection, but I suspect there was more to it than that. For the Orthodox as children searched for Easter eggs and grown-ups exchanged their painted Easter eggs, it was because they knew in their heart that Christ has indeed trampled down death and was alive, alive for evermore. That was worth celebrating and celebrating they did.

In pondering on this aspect of our prayer life I recalled in the early 1990’s attending the Paschal Vigil Mass at St. Mary Mag’s in Oxford. Afterwards the vicar and I walked the short distance to the Orthodox Church, which was celebrating Easter at the same time as the Western Church that year. What a difference! What a contrast! We both had been participating in a Liturgy that should have expressed the most rejoicing time of the whole Christian year, but did we feel it, really feel it? No. We had to go to the Orthodox Church to experience the unleashing of what joy really meant. It simply bubbled over in every movement, in every greeting and in the celebration of the Liturgy. That experienced taught me what Paul meant “to rejoice in the Lord.” Perhaps if we kept as severe a Lent as the committed Orthodox does then it might induce us to be more joyous at the celebration of the Resurrection, but I suspect there was more to it than that. For the Orthodox as children searched for Easter eggs and grown-ups exchanged their painted Easter eggs, it was because they knew in their heart that Christ has indeed trampled down death and was alive, alive for evermore. That was worth celebrating and celebrating they did.

In one of the couple of Bruno’s letters to his fellow monks at Chartreuse that has survived, even if the carrier did not in this instance, began also in similar vein:

In one of the couple of Bruno’s letters to his fellow monks at Chartreuse that has survived, even if the carrier did not in this instance, began also in similar vein:

Rejoice therefore my dear companions for your happy estate and to the extent to which divine grace has been showered upon you. Rejoice for your escape from the worldly waves of disturbance which spread shipwreck and peril. Rejoice in that you have found quiet, peace and security of a hidden port.

Let us follow the Orthodox, Paul and Bruno’s advice and glorify God our Father and the Lord Jesus Christ when we pray (Rom. 15. 6).

The second aspect of prayer for Paul was thanksgiving.

The second aspect of prayer for Paul was thanksgiving.

Apart from Galatians, as he was so angry with their stupidity (O stupid Galatians) in all his letters after his greetings Paul expressed his thanks to God and for his fellow Christians and set the example for us in our priority of praying. For example, to his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul exclaimed, “I thank my God always on your behalf for the grace of God which is given to you in Jesus Christ.” Paul knew that through Him we are enriched. In his very first letter to the Thessalonians, he thanked God for the joy he had received from his fellow Christians in Thessalonica ( I Thess. 3.9)

Apart from Galatians, as he was so angry with their stupidity (O stupid Galatians) in all his letters after his greetings Paul expressed his thanks to God and for his fellow Christians and set the example for us in our priority of praying. For example, to his first letter to the Corinthians, Paul exclaimed, “I thank my God always on your behalf for the grace of God which is given to you in Jesus Christ.” Paul knew that through Him we are enriched. In his very first letter to the Thessalonians, he thanked God for the joy he had received from his fellow Christians in Thessalonica ( I Thess. 3.9)

Indeed when we scan his letters we discover Paul’s gratitude for so many blessings he received not only from God but also from his co-workers such as Timothy and Silas, and early converts to the Way. In Philippians we find this glowing prayer.

Indeed when we scan his letters we discover Paul’s gratitude for so many blessings he received not only from God but also from his co-workers such as Timothy and Silas, and early converts to the Way. In Philippians we find this glowing prayer.

But even if I am poured out as a libation over the sacrifice and the offering of your faith, I am glad and rejoice with all of you – and in the same way you also must be glad and rejoice with me (Phil. 2. 17- 18).

But even if I am poured out as a libation over the sacrifice and the offering of your faith, I am glad and rejoice with all of you – and in the same way you also must be glad and rejoice with me (Phil. 2. 17- 18).

In this we also have an example of Paul encouraging Christians to pray in the same frame of mind. You can almost hear Paul reminding them not to worry as the Spirit within you will teach you to pray and then show you what is God’s will.

Thirdly, Paul taught the importance of intercessory prayer.

Thirdly, Paul taught the importance of intercessory prayer.

Paul certainly advocated what we call intercessory prayer – making supplication for others. In his case it was for the various Christian communities, as expressed in his letter to the Romans – a community he hoped to visit.

Paul certainly advocated what we call intercessory prayer – making supplication for others. In his case it was for the various Christian communities, as expressed in his letter to the Romans – a community he hoped to visit.

For God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son, that without ceasing I make mention of you always in my prayers (Rom. 1. 10). Later on in this letter he expressed that one of his supplications was for Israel itself, that it might be saved (Rom. 10.1).

For God is my witness, whom I serve with my spirit in the gospel of his Son, that without ceasing I make mention of you always in my prayers (Rom. 1. 10). Later on in this letter he expressed that one of his supplications was for Israel itself, that it might be saved (Rom. 10.1).

One of Paul’s concerns amongst those early converts to Jesus was for them to love one another as Jesus loved them and as he also did. So we find him informing the Thessalonians that he would intercede for them to be bound in love not only for their fellow Christians but indeed for all people and that they then would be found blameless in the day of the Lord’s coming (I Thess. 4. 12).

One of Paul’s concerns amongst those early converts to Jesus was for them to love one another as Jesus loved them and as he also did. So we find him informing the Thessalonians that he would intercede for them to be bound in love not only for their fellow Christians but indeed for all people and that they then would be found blameless in the day of the Lord’s coming (I Thess. 4. 12).

Paul also interceded for those fledging Christians to live not only prayerful lives but also to keep their bodies as a temple worthy of the Holy Spirit. So in Romans Paul besought the Lord that they keep their bodies as “a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God” (Rom. 12. 1.).

Paul also interceded for those fledging Christians to live not only prayerful lives but also to keep their bodies as a temple worthy of the Holy Spirit. So in Romans Paul besought the Lord that they keep their bodies as “a living sacrifice, holy, acceptable unto God” (Rom. 12. 1.).

Paul also sought the prayers of the early Christians for himself. In that letter to Christians in Rome towards the end we find this request:

Paul also sought the prayers of the early Christians for himself. In that letter to Christians in Rome towards the end we find this request:

I beseech you my brothers and sisters, for the love of Jesus Christ, and for the love of the Holy Spirit, that you strive together with me in prayers to God for me (Rom. 15.30).

I beseech you my brothers and sisters, for the love of Jesus Christ, and for the love of the Holy Spirit, that you strive together with me in prayers to God for me (Rom. 15.30).

Sometimes his request was very simple – e.g.: brothers and sisters pray for us ( I Thess. 5. 25). And also in his letter to Philemon, Paul simply expressed a trust in his prayers (v. 20).

In this aspect of praying we are pretty good in following Paul’s example, aren’t we? For some that is all prayer means – praying for others in need. And that it not a bad thing, as indirectly we are expressing that we believe in a God who cares for His people. Yet in that very intention of ours God is seeking us to enter into a deeper relation with Him.

In this aspect of praying we are pretty good in following Paul’s example, aren’t we? For some that is all prayer means – praying for others in need. And that it not a bad thing, as indirectly we are expressing that we believe in a God who cares for His people. Yet in that very intention of ours God is seeking us to enter into a deeper relation with Him.

Linked closely with intercessory prayer is petitionary prayer. As we have seen Paul encouraged those early converts to pray for themselves. It is only by asking God to give us grace that we can be healed, strengthened, have faith, and be a witness to the risen Lord.

Linked closely with intercessory prayer is petitionary prayer. As we have seen Paul encouraged those early converts to pray for themselves. It is only by asking God to give us grace that we can be healed, strengthened, have faith, and be a witness to the risen Lord.

Fourthly, how often did Paul teach that we had to die unto sin in order to experience that new life? To die unto sin means, firstly to acknowledge those sins and leave them behind in that life of freedom in Christ (Rom. 6. 5- 11). We need to clean out the old leaven in order to make a new batch of sincerity and truth (I Cor. 5. 6 -8).

Fourthly, how often did Paul teach that we had to die unto sin in order to experience that new life? To die unto sin means, firstly to acknowledge those sins and leave them behind in that life of freedom in Christ (Rom. 6. 5- 11). We need to clean out the old leaven in order to make a new batch of sincerity and truth (I Cor. 5. 6 -8).

If we are to bear one another’s burdens as Paul often advocated as he did to the Galatians it means we also have to forgive one another and pray for our brothers and sisters (Gal. 6. 2). Forgiveness is the heart of the Gospel, and we know we cannot be forgiven by Abba unless we forgive from our hearts.

If we are to bear one another’s burdens as Paul often advocated as he did to the Galatians it means we also have to forgive one another and pray for our brothers and sisters (Gal. 6. 2). Forgiveness is the heart of the Gospel, and we know we cannot be forgiven by Abba unless we forgive from our hearts.

Fifthly, praying also had its mystical component for Paul; that aspect of prayer that we associate with the monastic life and those like Paul who have been caught up to heaven by waiting upon Him. In II Cor. 12. 2-4 Paul spoke of such an experience:

Fifthly, praying also had its mystical component for Paul; that aspect of prayer that we associate with the monastic life and those like Paul who have been caught up to heaven by waiting upon Him. In II Cor. 12. 2-4 Paul spoke of such an experience:

I know a person in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven – whether in the body or out of it I know not; God knows. And I know that such a person – whether in the body or out of the body I do not know; God knows – was caught up in paradise and heard things that are not to be told, that no mortal is permitted to repeat.

I know a person in Christ who fourteen years ago was caught up to the third heaven – whether in the body or out of it I know not; God knows. And I know that such a person – whether in the body or out of the body I do not know; God knows – was caught up in paradise and heard things that are not to be told, that no mortal is permitted to repeat.

Probably this experience of Paul was during his time in the desert and perhaps his reason for sharing it with the Corinthians was because of those “super apostles” in Corinth who spoke of their ecstatic moments to the early Christians. Paul wanted his converts to know they were not the only ones.

Probably this experience of Paul was during his time in the desert and perhaps his reason for sharing it with the Corinthians was because of those “super apostles” in Corinth who spoke of their ecstatic moments to the early Christians. Paul wanted his converts to know they were not the only ones.

Yet what Paul shares is something we can all experience in those times when we offer up ourselves to our God in absolute abandonment in our stillness. Perhaps there may not be the same intensity that Paul spoke of, but nevertheless there is also something that relates to the mystic when we abandon ourselves to absorb the very presence of God.

Yet what Paul shares is something we can all experience in those times when we offer up ourselves to our God in absolute abandonment in our stillness. Perhaps there may not be the same intensity that Paul spoke of, but nevertheless there is also something that relates to the mystic when we abandon ourselves to absorb the very presence of God.

Pondering on being caught up into the highest heavens reminded me of a beautiful sonnet written by a war pilot just out of his teens during W.W. II and killed not long afterwards. I would like to share it with you.

Pondering on being caught up into the highest heavens reminded me of a beautiful sonnet written by a war pilot just out of his teens during W.W. II and killed not long afterwards. I would like to share it with you.

Oh! I have slipped the surly bonds of Earth

And danced the skies on laughter-silvered wings;

Sunward I've climbed, and joined the tumbling mirth

of sun-split clouds, — and done a hundred things

You have not dreamed of—wheeled and soared and swung

High in the sunlit silence. Hov'ring there,

I've chased the shouting wind along, and flung

My eager craft through footless halls of air.

Up, up the long, delirious, burning blue

I've topped the wind-swept heights with easy grace

Where never lark nor ever eagle flew—

And, while with silent lifting mind I've trod

The high untrespassed sanctity of space,

Put out my hand, and touched the face of God.

It is in Paul also that we learn of the various charismas, one of which was praying or speaking in tongues. What does our apostle have to say about this especially at worship?

It is in Paul also that we learn of the various charismas, one of which was praying or speaking in tongues. What does our apostle have to say about this especially at worship?

“I had rather speak five words with my understanding, that by my voice I might teach others also, than ten thousand words in an unknown tongue.” Writing to the Corinthians Paul advised, if one felt moved to pray like this, then one should be able to interpret it. Therefore, one who speaks in tongues should pray for the power to interpret.

In this extract Paul is suggesting that we cannot be too emotional and be carried away as it were in prayer and forget that it is an exercise and discipline, what we would call mental prayer.

In this extract Paul is suggesting that we cannot be too emotional and be carried away as it were in prayer and forget that it is an exercise and discipline, what we would call mental prayer.

For I pray in a tongue, my spirit prays but my mind is unproductive. What should I do then? I will pray with the spirit, but I will pray with the mind also; I will sing with the spirit, but I will sing praise with the mind also (I Cor. 14.13-15).

Prayer was very much an exercise of the mind as well as of the emotions according to Paul.

Prayer was very much an exercise of the mind as well as of the emotions according to Paul.

For Paul to be a good Jew and then a good Christian one had to pray. His advice was to pray unceasingly – pray always. By following Paul’s practice of prayer is a conscious, continuous and changing activity. For Paul it was not enough to greet the Lord in the early morn and then to forget about Him until bedtime. No, it was an activity that one was engrossed in all day long and even during the night. Recall such times when Paul was imprisoned in Philippi. He and Silas were praying and singing in the wee hours of the morning. Of course what Paul taught by example and encouragement became the heart of monastic life, especially as lived by the Carthusians whose speciality and gift has been singing the night vigil in the early hours.

For Paul to be a good Jew and then a good Christian one had to pray. His advice was to pray unceasingly – pray always. By following Paul’s practice of prayer is a conscious, continuous and changing activity. For Paul it was not enough to greet the Lord in the early morn and then to forget about Him until bedtime. No, it was an activity that one was engrossed in all day long and even during the night. Recall such times when Paul was imprisoned in Philippi. He and Silas were praying and singing in the wee hours of the morning. Of course what Paul taught by example and encouragement became the heart of monastic life, especially as lived by the Carthusians whose speciality and gift has been singing the night vigil in the early hours.

Paul’s advice has also become known as “the practice of the presence of God”, made famous centuries later by Bro. Lawrence, not a Carthusian but a Carmelite lay-brother. One can picture Paul on those long arduous trips chatting away to God, and as a faithful friend listening carefully to that inner voice. How else would he have been able to continue if he had not been conscious of the presence of God? How would he have survived the stonings, the beatings, the ship-wrecks? His prayers led to faith and a belief in His God that was always with Him, even in adversity. What Paul taught and lived influenced so many down the ages. One of those very much influenced by him was Andrewes who had this advice about praying.

Paul’s advice has also become known as “the practice of the presence of God”, made famous centuries later by Bro. Lawrence, not a Carthusian but a Carmelite lay-brother. One can picture Paul on those long arduous trips chatting away to God, and as a faithful friend listening carefully to that inner voice. How else would he have been able to continue if he had not been conscious of the presence of God? How would he have survived the stonings, the beatings, the ship-wrecks? His prayers led to faith and a belief in His God that was always with Him, even in adversity. What Paul taught and lived influenced so many down the ages. One of those very much influenced by him was Andrewes who had this advice about praying.

When you awake in the morning, shut and close up the entrance to thy heart, from all unclean, profane,

When you awake in the morning, shut and close up the entrance to thy heart, from all unclean, profane,  and evil thoughts, and let the consideration of God and goodness enter in.

and evil thoughts, and let the consideration of God and goodness enter in.

When you have arisen and are ready, return thyself to thy closet, or other private place, and offer to God, the first fruits of the day, and in praying to him and praising him, remember:

1. To give him thanks, for thy quiet rest received, for delivering thee from all dangers, ghostly and bodily, and for all other his benefits to thee.

To give him thanks, for thy quiet rest received, for delivering thee from all dangers, ghostly and bodily, and for all other his benefits to thee.

2. Offer unto him thyself, and all things that thou dost possess, and desire him to dispose of thee and them, according to his good pleasure.

Offer unto him thyself, and all things that thou dost possess, and desire him to dispose of thee and them, according to his good pleasure.

3. Crave his grace to guide thee, and to strengthen thee from, and against all temptations, that so you may do nothing during the day contrary to his will.

Crave his grace to guide thee, and to strengthen thee from, and against all temptations, that so you may do nothing during the day contrary to his will.

4. And lastly, beg of him, (according to how we should pray) all things needful for the soul and body.

And lastly, beg of him, (according to how we should pray) all things needful for the soul and body.

Praying alone for Andrewes also meant those “private meditations and conferences between God and our souls”, the contemplative approach. Often in his liturgical sermons too he advocated this approach. For instance in his extant sermons for Good Friday he begged his auditors to spend much time simply contemplating the cross. “Blessed are the hours that are so spent!” he told them. Recall those many times that Paul told his fellow Christians that all was “in Christ”. To contemplate the cross and Christ’s suffering was part of one’s prayer life for Paul. Unless one contemplated that earnestly, then there could not be the joy from knowing that Christ had conquered death and was alive. That was the heart of faith and prayer.

For Paul the key to a prayerful life was perseverance. How often did Paul remind us of this and indeed the early Fathers after him who called perseverance the queen of all virtues?

For Paul the key to a prayerful life was perseverance. How often did Paul remind us of this and indeed the early Fathers after him who called perseverance the queen of all virtues?

We have to let go. We must have faith and surrender completely. Paul himself must have known this so often in his life when he was rejected, thrown out of towns, shipwrecked and left for dead after stoning. It was only that perseverance, that greatest of all virtues, that enabled him to keep going and us too in our world where we have to face so many distractions and diversities from our Christian values. Let’s take encouragement from the greatest of all the apostles.

In everything give thanks

In everything give thanks

To give him thanks, for thy quiet rest received, for delivering thee from all dangers, ghostly and bodily, and for all other his benefits to thee.

To give him thanks, for thy quiet rest received, for delivering thee from all dangers, ghostly and bodily, and for all other his benefits to thee. Offer unto him thyself, and all things that thou dost possess, and desire him to dispose of thee and them, according to his good pleasure.

Offer unto him thyself, and all things that thou dost possess, and desire him to dispose of thee and them, according to his good pleasure. Crave his grace to guide thee, and to strengthen thee from, and against all temptations, that so you may do nothing during the day contrary to his will.

Crave his grace to guide thee, and to strengthen thee from, and against all temptations, that so you may do nothing during the day contrary to his will. And lastly, beg of him, (according to how we should pray) all things needful for the soul and body.

And lastly, beg of him, (according to how we should pray) all things needful for the soul and body.