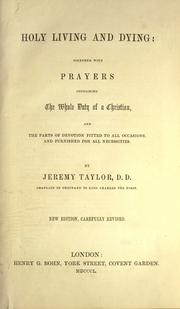

JEREMY TAYLOR (1613 - 1667)

BISHOP OF DOWN AND CONNOR

Like Andrewes’ Preces Privatae, Taylor’s Holy Living and Holy Dying have endeared him to modern times. Anybody who takes Anglican and Catholic Spirituality seriously knows all these works well.

In Holy Living he portrayed the beauty of the divine within each soul as a cabinet “of the mysterious Trinity”. What a beautiful reflection to introduce this Caroline divine.

As Taylor was born in Cambridge his education was at Cambridge university. Like Cosin he attended Caius and Gonville College where he received his B.A. in 1631 and M.A. in 1634. The year before he was ordained even though he was under age. After been awarded his M.A. he was appointed praelector in rhetoric by the master of Caius. It wouls seem that Taylor made an impression on Laud very early in life and took him under his wing. That resulted in being admitted as a Fellow of All Souls College, even though the warden, Gilbert Sheldon objected (something he was still doing against Taylor after the Restoration) but as Chancellor Laud overrode him. Shortly afterwards he became a chaplain to the Archbishop and a chaplain-in-ordinary to Charles I.

...

Laud had been executed before the war ended, Charles would meet the same fate in 1649 and in the autumn of the next year Lady Carbery also died in childbirth. She too was a devoted Anglican and obviously she and Taylor were soul mates. To read the panegyric he delivered at her funeral blends time and eternity, her life and the new life, death and the journey is so beautiful, sensitive and spiritual. It reveals two lovely souls – the departed and the living preacher.

Yet the day did come when sunshine brightened the horizons once again for the faithful Anglicans after that horrible time under Cromwell. Charles II was restored to his rightful crown and with him the English Church. Taylor was in London when Charles returned to London triumphantly on 29th May, 1660 for the publication of Ductor Dubitantium.

He would die as a consequence of his pastoral ministry by visiting those suffering from the fever. In death it would show that he died almost a pauper as he had given most of his money to the poor. Taylor certainly lived the teaching of the Christ.

Still he showed the strong faith and inner strength that enabled him to live joyfully and pastorally in his writings. It is these that enable his piety and moral/aesthetical theology to live on in our modern world and to help us as they did for thousands in those terrible times in the mid- sixteenth century.

THE DEVOTIONAL WRITINGS OF JEREMY TAYLOR

Much of Taylor's writings were devotional to encourage Christians to live piously and in loving God and their neighbours. They were written also to encourage Christians to live the ascetic life as had been lived by Christians from the earliest times but also to imitate the life of Christ.

Perhaps his outstanding contribution was to publish The Exemplar, the first book in English on the life of Christ and for Christians to imitate that life. Published in that doleful year that witnessed the execution of Charles I it is a book of great beauty and spiritual insight in its series of discourses, reflections or meditations and prayers. In the preface Taylor states that the reason for this work on the Saviour’s life is to encourage Christians to imitate Him.

Section I

The History of the Conception of Jesus

1.WHEN the fulness of time was come, after the frequent repeti¬tion of promises, the expectation of the Jewish nation, the longings and tedious waitings of all holy persons, the departure of the "scep¬tre from Judah, and the lawgiver from between his feet;" when the number of Daniel's years was accomplished, and the Egyptian and Syrian kingdoms had their period ; God, having great compassion towards mankind, remembering His promises, and our great necessi¬ties, sent His Son into the world, to take upon Him our nature, and all that guilt of sin which stuck close to our nature, and all that punishment which was consequent to our sin : which came to pass after this manner;

2. In the days of Herod the king, the angel Gabriel was sent from God to a city of Galilee named Nazareth, to a holy maid called Mary, espoused to Joseph, and found her in a capacity and excellent disposition to receive the greatest honour that ever was done to the daughters of men. Her employ ment was holy and pions, her person young, her years florid and springing, her body chaste, her mind humble, and a rare repository of divine graces. She was full of grace and excellencies; and God poured upon her a full measure of honour, in making her the mother of the Messias for the " angel came to her, and said, Hail, thou that art highly favoured, the Lord is with thee; blessed art thou among women."

3. We cannot but imagine the great mixture of innocent disturbances and holy passions, that in the first address of the angel did rather discompose her settledness and interrupt the silence of her spirits, than dispossess her dominion which she ever kept over those subjects which never had been taught to rebel beyond the mere possibilities of natural imperfection. But if the angel appeared in the shape of a man, it was an unusual arrest to the blessed Virgin, who was accustomed to retirements and solitariness, and had not known an experience of admitting a comely person, but a stranger, to her closet and privacies. But if the heavenly messenger did retain a diviner form, more symbolical to angelical nature and more proportionable to his glorious message, although her daily employment was a conversation with angels, who in their daily ministering to the saints did behold her chaste conversation, coupled with fear, yet they used not any affrighting glories in the offices of their daily attendances, but were seen only by spiritual discernings. However, so it happened, that "when she saw him, she was troubled at his saying, and cast in her mind what manner of salutation this should be."

4. But the angel, who came with designs of honour and comfort to her, not willing that the inequality and glory of the messenger should, like too glorious a light to a weaker eye, rather confound the faculty than enlighten the organ, did, before her thoughts could find a tongue, invite her to a more familiar confidence than possibly a tender virgin, though of the greatest serenity and composure, could have put on in the presence of such a beauty and such a holiness : and "the angel said unto her, Fear not, Mary, for thou hast found favour with God ; and behold, thou shalt conceive in thy womb, and bring forth a son, and shalt call His name Jesus."

5. The holy Virgin knew herself a person very unlikely to be a mother; for although the desires of becoming a mother to the Messias were great in every of the daughters of Jacob, and about that time the expectation of His revelation was high and pregnant, and therefore she was espoused to an honest and a just person of her kindred and family, and so might not despair to become a mother; yet she was a person of a rare sanctity, and so mortified a spirit, that for all this desponsation of her, according to the desire of her parents and the custom of the nation, she had not set one step toward the consummation of her marriage, so much as in thought; and possibly had set herself back from it by a vow of chastity and holy celibate : for " Mary said unto the angel, How shall this be, seeing I know not a man ?"

6.But the angel, who was a person of that nature which knows no conjunctions but those of love and duty, knew that the piety of her soul and the religion of her chaste purposes was a great imitator of angelical purity, and therefore perceived where the philosophy of

her question did consist; and being taught of God, declared that the manner should be as miraculous as the message itself was glorious. For the angel told her, that this should not be done by any way, which our sin and the shame of Adam had unhallowed, by turning nature into a blush, and forcing her to a retirement from a public attesting the means of her own preservation; but the whole matter was from God, and so should the manner be : for "the angel said unto her, The Holy Ghost shall come upon thee, and the power of the Highest shall overshadow thee : therefore also that holy thing which shall be born of thee shall be called the Son of God."

7. When the blessed Virgin was so ascertained that she should be a mother' and a maid, and that two glories, like the two lumina¬ries of heaven, should meet in her, that she might in such a way become the mother of her Lord that she might with better advan¬tages be His servant; then all her hopes and all her desires received such satisfaction, and filled all the corners of her heart so much, as indeed it was fain to make room for its reception. But she, to whom the greatest things of religion and the transportations of devotion were made familiar by the assiduity and piety of her daily practices, however she was full of joy, yet she was carried like a full vessel, with¬out the violent tossings of a tempestuous passion or the wrecks of a stormy imagination : and, as the power of the Holy Ghost did descend upon her like rain into a fleece of wool, without any obstre¬porous noises or violences to nature, but only the extraordinariness of an exaltation ; so her spirit received it with the gentleness and tranquillity fitted for the entertainment of the spirit of love, and a quietness symbolical to the holy guest of her spotless womb, the Lamb of God; for she meekly replied, " Behold the handmaid of the Lord ; be it unto me according unto thy word : and the angel departed from her," having done his message. And at the same time the Holy Spirit of God did make her to conceive in her womb the immaculate Son of God, the Saviour of the world.

Ad SECTION I.

Consideration upon the annunciation of the blessed Virgin Mary, and the conception of the holy Jesus.

1. THAT which shines brightest presents itself first to the eye; and the devout soul, in the chain of excellent and precious things which are represented in the counsel, design, and first beginnings of the work of our redemption, both not leisure to attend the twinkling of the lesser stars, till it hath stood and admired the glory and emi¬nencies of the divine love manifested in the incarnation of the Word eternal. God had no necessity in order to the conservation or the heightening His own felicity, but out of mere and perfect charity and the bowels of compassion sent into the world His only Son, for remedy to human miseries, to ennoble our nature by an union with divinity, to sanctify it with His justice, to enrich it with His grace, to instruct it with His doctrine, to fortify it with His example, to rescue it from servitude, to assert it into the liberty of the sons of God, and at last to make it partaker of a beatifical resurrection.

2. God, who in the infinite treasures of His wisdom and provi¬dence could have found out many other ways for our redemption than the incarnation of His eternal Son, was pleased to choose this, not only that the remedy by man might have proportion to the causes of our ruin, whose introduction and intromission was by the prevarication of man; but also that we might with freer dispensation receive the influences of a Saviour with whom we communicate in nature. Although Abana and Pharpar, rivers of Damascus, were of greater name and current, yet they were not so salutary as the waters of Jordan to cure Naaman's leprosy. And if God had made the remedy of human nature to have come all the way clothed in pro¬digy, and every instant of its execution had been as terrible, affright¬ing, and as full of majesty, as the apparitions upon mount Sinai; yet it had not been so useful and complying to human necessities as was the descent of God to the susception of human nature, whereby (as in all medicaments) the cure is best wrought by those instruments which have the fewest dissonances to our temper, and are the nearest to our constitution. For thus the Saviour of the world became human, alluring, full of invitation and the sweetnesses of love, exemplary, bumble, and medicinal.

3. And if we consider the reasonableness of the thing, what can be given more excellent for the redemption of man than the blood of the Son of God ? And what can more ennoble our nature, than that by the means of His holy humanity it was taken up into the cabinet of the mysterious Trinity? What better advocate could we have for us, than He that is appointed to be our judge? And what greater hopes of reconciliation can be imagined, than that God, in whose power it is to give an absolute pardon, hath taken a new nature, entertained an office, and undergone a life of poverty, with a purpose to procure our pardon ? For now, though, as the righteous judge, He will judge the nations righteously; yet, by the susception of our nature, and its appendent crimes, He is become a party; and, having obliged Himself as man, as He is God He will satisfy, by putting the value of an infinite merit to the actions and sufferings of Aga humanity. And if He had not been God, He could not have given us remedy; if He had not been man, we should have wanted the excellency of example.

4. And till now, human nature was less than that of angels; but, by the incarnation of the Word, was to be exalted above the cherubims : yet the archangel Gabriel, being dispatched in embassy to represent the joy and exaltation of his inferior, instantly trims his wings with love and obedience, and hastens with this narrative to the holy Virgin. And if we should reduce our prayers to action, and do God's will on earth, as the angels in heaven do it, we should promptly execute every part of the divine will, though it were to be instrumental to the exaltation of a brother above ourselves; knowing no end but conformity to the divine will, and making simplicity of intention to be the fringes and exterior borders of our garments.

5.When the eternal God meant to stoop so low as to be fixed to our centre, He chose for His mother a holy person and a maid, but yet affianced to a just man, that He might not only be secure in the innocency, but also provided for in the reputation of His holy mother : teaching us, that we must not only satisfy ourselves in the purity of our purposes and hearty innocence, but that we must provide also things honest in the sight of all men, being free from the suspicion and semblances of evil ; so making provision for private innocence and public honesty : it being necessary, in order to charity and edification of our brethren, that we hold forth no impure flames or smoking firebrands, but pure and trimmed lamps, in the eyes of all the world.

6. And yet her marriage was more mysterious; for as, besides the miracle, it was an eternal honour and advancement to the glory of virginity, that He chose a virgin for His mother, so it was in that manner attempered, that the Virgin was betrothed, lest honourable marriage might be disreputed and seem inglorious by a positive rejection from any participation of the honour. Divers of the old doctors, from the authority of Ignatius, add another reason, saying, that the blessed Jesus was therefore born of a woman betrothed and under the pretence of marriage, that the devil, who knew the Messias was to be born of a virgin, might not expect Him there, but so be ignorant of the person till God had served many ends of providence upon Him.

7. The angel, in his address, needed not to go in inquisition after a wandering fire, but knew she was a star fixed in her own orb : he found her at home; and lest that also might be too large a

circuit, she was yet confined to a more intimate retirement; she was in her oratory, private and devout. There are some curiosities so bold and determinate, as to tell the very matter of her prayers, and that she was praying for the salvation of all the world, and the revelation of the Messias, desiring she might be so happy as to kiss the feet of her who should have the glory to be His mother. We have no security of the particular; but there is no piety so diffident as to require a sign to create a belief that her employment at the instant was holy and religious; but in that disposition she received a grace which the greatest queens would have purchased with the quitting of their diadems, and hath consigned an excellent document to all women, that they accustom themselves often to those retirements where none but God and His angels can have admittance. For the holy Jesus can come to them too, and dwell with them, hallowing their souls, and consigning their bodies to a participation of all His glories ; but recollecting of all our scattered thoughts and exterior extravagances, and a receding from the inconveniences of a too free conversation, is the best circumstance to dispose us to a heavenly visitation.

8.The holy Virgin, when she saw an angel and heard a testimony from heaven of her grace and piety, was troubled within herself at the salutation and the manner of it : for she had learned, that the affluence of divine comforts and prosperous successes should not exempt us from fear, but make it the more prudent and wary, lest it entangle us in a vanity of spirit ; God having ordered that our spirits should be affected with dispositions in some degrees contrary to exterior events, that we be fearful in the affluence of prosperous things, and joyful in adversity; as knowing that this may produce benefit and advantage; and the changes that are consequent to the other are sometimes full of mischiefs, but always of danger. But her silence and fear were her guardians; that, to prevent excrescences of joy; this, of vainer complacency.

9. And it is not altogether inconsiderable to observe, that the holy Virgin came to a great perfection and state of piety by a few, and those modest and even, exercises and external actions. St. Paul travelled over the world, preached to the gentiles, disputed against the Jews, confounded heretics, writ excellently learned letters, suffered dangers, injuries, affronts, and persecutions to the height of wonder, and by these violences of life, action, and patience, obtained the crown of an excellent religion and devotion. But the holy Virgin, although she was engaged sometimes in an active life, and in the exercise of an ordinary and small economy and government or ministries of a family, yet she arrived to her perfections by the means of a quiet and silent piety, the internal actions of love, devotion, and contemplation; and instructs us, that not only those who have opportunity and powers of a magnificent religion, or a pompous charity, or miraculous conversion of souls, or assiduous and effectual preachings, or exterior demonstrations of corporal mercy, shall have the greatest crowns, and the addition of degrees and accidental rewards; but the ;lent affections, the splendours of an internal devotion, the unions of love, humility, and obedience, the daily offices of prayer and praises sung to God, the acts of faith and fear, of patience and meekness, of hope and reverence, repentance and cha¬rity, and those graces which walk in a veil and silence, make great ascents to God, and as sure progress to favour and a crown, as the more ostentous and laborious exercises of a more solemn religion. No man needs to complain of want of power or opportunities for religious perfections : a devout woman in her closet, praying with much zeal and affections for the conversion of souls, is in the same order to a "shining like the stars in glory," as he who by excellent discourses puts it into a more forward disposition to be actually performed. And possibly her prayers obtained energy and force to my sermon, and made the ground fruitful, and the seed spring up to life eternal. Many times God is present in the still voice and private retirements of a quiet religion, and the constant spiritualities of an ordinary life, when the loud and impetuous winds, and the shining fires of more laborious and expensive actions, are profitable to others only, like a tree of balsam, distilling precious liquor for others, not for its own use.

THE PRAYER.

0 eternal and almighty God, who didst send Thy holy angel in embassy to the blessed Virgin mother of our Lord, to manifest the actuating Thine eternal purpose of the redemption of mankind by the incarnation of Thine eternal Son; put me, by the assistances of Thy divine grace, into such holy dispositions, that I may never impede the event and effect of those mercies which in the coun¬sels of Thy predestination Thou didst design for me. Give me a promptness to obey Thee to the degree and semblance of angelical alacrity; give me holy purity and piety, prudence and modesty, like those excellencies which Thou didst create in the ever-blessed Virgin, the mother of God : grant that my employment be always holy, unmixed with worldly affections, and, as much as my condi¬tion of life will bear, retired from secular interests and disturbances; that I may converse with angels, entertain the holy Jesus, conceive Him in my soul, nourish Him with the expresses of most innocent and holy affections, and bring Him forth and publish Him in a life of piety and obedience, that He may dwell in me for ever, and I may for ever dwell with Him, in the house of eternal pleasures and glories, world without end. Amen.

( The rest of this meditation can be easily accessed online.A

Another devotional work of Taylor was The Golden Grove. One of the features of this book is a collection of festival hymns for the Christian Year. It began with the one for Advent:

It also contains rules for living each day piously beginning in the morning. "Rise as soon as your health and occasions shall permit; but it is good to be as regular as you can, and as early." On awakening give some thanksgiving and praise to God. On dressing offer ejaculatory prayers "fitted to the several actions of dressing" and when semi-attired "kneel and say the Lord's prayer". When dressing is complete, "retire to your closet" for your devotions which should be divided into seven acts of piety: an act of adoration, thanksgiving, oblation, confession, petition, intercession and meditation, or serious, deliberate, useful reading of the holy Scriptures. After praying, "consider what you are to do that day, what matter of business is like to employ you or tempt you; and take particular resolutions against that." If their are children and /or servants in the household "take care" they "say their prayers before they begin their work." So that they can “go about the affairs of your house and proper employment, ever avoiding idleness." "Before dinner ... let some parts" of "the public prayers of the Church" be said amongst the household.

Taylor’s first scholarly work, Episcopacy Asserted, was published in the year that the Long Parliament abolished episcopacy. It was a brave soul to write such a work in a climate so hostile to the English Church and King, but Taylor passionately believed in the divine origin of episcopacy and to the injury and imprisonment of bishops and priests. All this is reflected in his dedication

Of all his writings, the one that caused most stir, well in Anglican hierarchy, was Unum Necessarium. In the preface of this work Taylor stated his belief on original sin was different from the Ninth Article that states “the natural propensity to evil, and the perpetual lusting of the flesh against the spirit, deserves the anger of God and damnation.” This “I so earnestly dispute,” states Taylor. He argued:

Taylor was especially concerned about damnation for infants who die before baptism. He maintained maintains that all infants are innocent and therefore should not be inflicted with the "punishment of Adam's sin". He argued:

To condemn infants to hell for the fault of another, is to deal worse with them than God did to the very devils, ... it cannot be supposed that God should damn infants or innocents without a cause, ... And if God cannot be supposed to damn infants or innocents without a cause, and therefore He so ordered it that a cause should both be waiting, but He infallibly and irresistibly made them guilty of Adam's sins; is not this to resolve to make them miserable, and then with scorn to triumph in their sad condition? For if they could not deserve to perish without a fall of their own, how could they deserve to have such a fault put upon them.

He was emphatic "that for Adam's sin alone no man but himself is or can justly be condemned to the bitter pains of eternal life." When challenged whether he did accept the fact of "original sin", Taylor made it clear he did. Undoubtedly, he declared it is "affirmed by all antiquity, upon many grounds of scripture, that Adam sinned, and his was personally his, but derivately ours; that is, it did great hurt to us, to our bodies directly, to our souls indirectly and accidentally." There was no question that "Adam turned his back upon the sun, and dwelt in the dark and the shadow: he sinned, and fell into God's displeasure, and was made naked of all his supernatural endownments, and was ashamed and sentenced to death, and deprived of the means of long life, and of the sacrament and instrument of immortality, I mean the true of life." However for Taylor the main thing was that "when God was angry with Adam, the man fell from the state of grace; for God withdrew His grace, and we returned to the state of mere nature, of our prime creation." Hence "by Adam's fall [we] received evil enough to undo us, and ruin us all; but yet the evil did so descend upon us,... God's service was made much harder, but not impossible; mankind was miserable, but not desperate, we contracted an actual mortality, but we were redeemable from the power of death; sin was easy and ready at the door, but it was resistable; our will was abused, but yet not destroyed; our understanding was cozened, but yet still capable of the best instructions; and though the devil has wounded us, yet God sent His son, who like to the good Samaritan poured oil and wine into our wounds, and we were cured."

The core of Taylor’s teaching was based on the Pauline theology of the natural versus the spiritual: “‘The first Adam was made a living soul; the last Adam was made a quickening spirit’" Thus "the first man is of the earth, earthly; the second man is the Lord from Heaven." From the first "we derive an earthly life, ... an inherit nothing but temporal life and corruption; ... from the Second we obtain a heavenly [life]." Consequently "the sin of Adam brought hurt to the body directly, [and] indirectly it brought hurt to the soul." By our natural weakness inherited from Adam's sin, "man cannot do or perform the law of God" without grace from the second Adam.

Taylor in his teaching of death as a consequence of sin, began with a quote from one of the earliest Christian theologians Justin Martyr, "‘Adam by his sin made all his posterity liable to sin, and subjected them to death.’", Taylor continued it is Adam's sin [which] infected us with death, and this infection we derive in our birth, that is, we are born mortal. Adam's sins was imputed to us unto a natural death; in him we are sinners, as in him we die. But this sin is not real and inherent, but imputed only to such a degree." By referring to St. Cyprian, Taylor cited an example of what he meant by appealing once again to an infant. "An infant has not sinned, save only that being carnally born of Adam, in his first birth he has contracted the contagion of the old death." Taylor argued that death is the consequence of sin, not "a punishment" nor "an evil inflicted for sin". Taylor insisted there was "nothing else "in scripture expressed to be the effect of Adam's sin; and beyond this without authority we must not go."

He has used such rare acts of the Spirit for the extermination of it, since He sent His only Son to destroy it; and He is perpetually destroying it and will at last make it that it will be no more at all, but in the house of cursing, the horrible regions of damnation.

Thus Unum Necessarium was repentance. In its preface Taylor declared:

Examine his conscience most curiously, according as his time will permit, and his other abilities; because he ought to be sure that his intentions are so real to God and to religion, that he has already within him a resolution so strong, a repentance so holy, a sorrow so deep, a hope so pure, a charity so sublime, that no temptations, no time, no health, no interest could in any circumstance of things ever tempt him from God and prevail.

When writing about repentance of sins it is obvious that Taylor had in mind the sacrament of confession as a normal means of being absolved from sin. It was imperative that those who had difficulty in "expressing sorrow for their sins should seek "the ministry of a spiritual man." As Taylor pointed out "Confession of sins to a minister of religion ... is one of the most charitable works in the world to ourselves."

And let things be at the worst they can, yet he who confesses his sins to God shall find mercy at the hands of God; and He has established a holy ministry in His church to absolve all penitents; and if I go to one of them, and tell the sad story of my infirmity, the good mean will presently warrant my pardon, and absolve me.

THE SACRAMENT OF CONFESSION

REPENTANCE

Full of mercy, full of love,

Look upon us from above!

Thou who taugh'st the blind man's night

To entertain a double light,

Thine, and the day's (and that Thine too;)

The lame away his crutches threw;

The parched crust of leprosy

Return'd unto its infancy;

The dumb amazed was to hear

His own unchain'd tongue strike his ear;

Thy powerful mercy did even chase

The devil from his usurp'd place,

Where Thou Thyself should'st dwell, not he.

Oh, let Thy love our pattern be;

Let Thy mercy teach one brother

To forgive and love one another,

That copying Thy mercy here,

Thy goodness may hereafter rear

Our souls unto Thy glory, when

Our dust shall cease to be with men.

- Taylor's Poem on Charity

Jeremy Taylor is an inspiration to all Catholic Christians of one who loved the Church and her Sacraments and Prayers. He was one of the leading moral theologians of his time and his devotional works have inspired many souls to live the Christian life in love of God and others as Taylor did.

A prayer for the whole Catholic Church

Marianne Dorman

Return to Index