PALLADIUS writing in the early 5thC, in his Lausiac History of life in the desert told of his encounters with women. In his travels he came across a convent of 400 women and a remarkable abbess, Amma Talis, who has lived ascetically for 80 years. He revealed how spiritually free these women in the desert seemed to be, and of their generous hospitality.

"In this city of Antinoe there are twelve convents of women; in one of them I met Amma Talis, an old woman who had spent eighty years in asceticism, as she and the neighbours told me. With her dwelt sixty young women who loved her so greatly that no key even was fixed on the outer wall of the monastery, as in other monasteries, but they were kept in by love of her. Such a height of impassivity did the old woman reach that when I entered and sat down she came and sat by me and put her hands on my shoulders in a transport of freedom."

"In this city of Antinoe there are twelve convents of women; in one of them I met Amma Talis, an old woman who had spent eighty years in asceticism, as she and the neighbours told me. With her dwelt sixty young women who loved her so greatly that no key even was fixed on the outer wall of the monastery, as in other monasteries, but they were kept in by love of her. Such a height of impassivity did the old woman reach that when I entered and sat down she came and sat by me and put her hands on my shoulders in a transport of freedom."

Palladius also mentioned that "in this monastery there was a disciple of hers by name Taor, a virgin who had been thirty years in the monastery; [but] she would never accept a new habit or hood or shoes, saying: 'I do not need them, lest I be forced also to go out.'" He related how Taor had told him that she did not go out with her sisters on Sunday "on Sunday to church for the Communion;" instead she stayed home in her old rags working ceaselessly. Yet even in her "rags" she was beautiful to those who looked upon her. However such was her chastity and modesty that onlookers were overcome with reverence and fear.

Palladius also mentioned that "in this monastery there was a disciple of hers by name Taor, a virgin who had been thirty years in the monastery; [but] she would never accept a new habit or hood or shoes, saying: 'I do not need them, lest I be forced also to go out.'" He related how Taor had told him that she did not go out with her sisters on Sunday "on Sunday to church for the Communion;" instead she stayed home in her old rags working ceaselessly. Yet even in her "rags" she was beautiful to those who looked upon her. However such was her chastity and modesty that onlookers were overcome with reverence and fear.

Pachomius, known as the father of cenobitic monastery, in the 3rdC wrote a rule not only for his monks, but also for his sister, Mary and her nuns. In their double monastery they shared the manual labourers, monks building the nuns' monastery, and the nuns making the monks' clothes. This double monastery set-up became very popular in those first few centuries of Christianity.

Pachomius, known as the father of cenobitic monastery, in the 3rdC wrote a rule not only for his monks, but also for his sister, Mary and her nuns. In their double monastery they shared the manual labourers, monks building the nuns' monastery, and the nuns making the monks' clothes. This double monastery set-up became very popular in those first few centuries of Christianity.

Monastic life for women also had its roots in the great houses of noble women on the Aventine Hill in Rome in the 4thC. Two names stand out here, Marcella and Paula. Marcella's mother, Albina, had provided a home for the Orthodox bishop, Athanasius during one of his stints in exile in 340, who tutored Marcella in the ways of the ascetic life. When we first meet Marcella she is a young widow (her husband died after 7 months of marriage), and living the ascetic life taught to her by Athanasius with other women she had attracted to live in a similar way, some of whose names we know : Sophronia, Asella, Principia and Lea.

Close by, Paula, a relative of Marcella, had another group. These included members of her own family, Furia, Fabiola and Marcellina, the sister of Ambrose. They joined with Marcella each day in praying, studying, reciting the psalms and learning about the ascetic life from her. When Jerome arrived in Rome in 382 Marcella invited him to give lectures on the Scriptures. As well as this he taught them to sing the psalms in Hebrew and to practise scriptural exegesis themselves.

Jerome was an irascible character, and his friendship with these women gave some stability to his life. When he was forced to leave Rome, he went to Jerusalem and Paula went with him. It was Paula's wealth that enabled Jerome to pursue his life's work of translating the Scriptures into Latin. Palladius gave an interesting insight to the relationship of these two when he related how Paula was hindered by Jerome. "For though she was able to surpass all, having great abilities, he hindered her by his jealousy, having induced her to serve his own plan."

Jerome was an irascible character, and his friendship with these women gave some stability to his life. When he was forced to leave Rome, he went to Jerusalem and Paula went with him. It was Paula's wealth that enabled Jerome to pursue his life's work of translating the Scriptures into Latin. Palladius gave an interesting insight to the relationship of these two when he related how Paula was hindered by Jerome. "For though she was able to surpass all, having great abilities, he hindered her by his jealousy, having induced her to serve his own plan."

Eventually Paula and Jerome founded a double monastery in Bethlehem where all followed basically the same rule. The women were divided into three groups for meals and during work periods, and came together at the third, sixth and ninth hours, at evening and in the middle of the night for the singing of the psalms. On Sunday they walked to Mass as a corporate body, and on returning were handed their individual work assignments for the week such as scrubbing floors, cooking, sewing, and helping the poor. Much stress was placed on knowing the Scriptures, which they had to learn by heart, which of course included the psalter, recited in its entirety each day.

Eventually Paula and Jerome founded a double monastery in Bethlehem where all followed basically the same rule. The women were divided into three groups for meals and during work periods, and came together at the third, sixth and ninth hours, at evening and in the middle of the night for the singing of the psalms. On Sunday they walked to Mass as a corporate body, and on returning were handed their individual work assignments for the week such as scrubbing floors, cooking, sewing, and helping the poor. Much stress was placed on knowing the Scriptures, which they had to learn by heart, which of course included the psalter, recited in its entirety each day.

This monastery attracted many Christians in the Mediterranean area, including Alypius, the close friend of Augustine, whilst from Spain came Lucinius and his wife Theodora who wanted to imitate the Bethlehem model.

When Paula died in 404 her daughters, Eustochium and the younger Paula took over the administration of the monastery. Before leaving Rome for Jerusalem, another daughter of Paula, Blesilla, had died from extreme asceticism. Although her mother was broken-hearted at her daughter's death, she and Jerome were nevertheless blamed for her death.

Back in Rome Marcella's household/convent increased in size, and she was addressed as Mother. Although she received many invitations to go to Bethlehem, she refused, and Jerome accused her of anti-semitism. Alas for Marcella and her company of virgin women the house was plundered and burnt with the sack of Rome in 410 and Marcella died soon afterwards.

Back in Rome Marcella's household/convent increased in size, and she was addressed as Mother. Although she received many invitations to go to Bethlehem, she refused, and Jerome accused her of anti-semitism. Alas for Marcella and her company of virgin women the house was plundered and burnt with the sack of Rome in 410 and Marcella died soon afterwards.

Under Marcella women learned to pray, to dispose of their possessions, to live in simplicity, and to govern their own lives. They continued to sing the psalms in Hebrew, the only people in the West to do so. Irrespective of rank they all were involved in manual labour and all ate together and all dressed alike. Even the Pope consulted them when he ran into theological difficulties.

Another outstanding ascetic woman was Melania the elder who was a member of the patrician Antonia family of Rome, Melania (343-410) was the daughter of a consul and the wife of a prefect. Following the deaths of her husband, Valerius Maximus, and two of her three children in short succession Melania made a pilgrimage to Egypt and the Holy Land. She put her son in the care of a tutor and distributed some of her wealth. In Egypt, she met and became the patroness of Rufinus. Their relationship lasted for twenty years. In Jerusalem c.380 they established two monasteries on the Mount of Olives. She headed a community of 50 nuns. Around 400 she returned to Rome to see her family. Whilst there she persuaded her granddaughter, also Melania, (known as Melanie the Younger 385- 448) to adopt a more ascetical life and to take her over her monastic baton.

Another outstanding ascetic woman was Melania the elder who was a member of the patrician Antonia family of Rome, Melania (343-410) was the daughter of a consul and the wife of a prefect. Following the deaths of her husband, Valerius Maximus, and two of her three children in short succession Melania made a pilgrimage to Egypt and the Holy Land. She put her son in the care of a tutor and distributed some of her wealth. In Egypt, she met and became the patroness of Rufinus. Their relationship lasted for twenty years. In Jerusalem c.380 they established two monasteries on the Mount of Olives. She headed a community of 50 nuns. Around 400 she returned to Rome to see her family. Whilst there she persuaded her granddaughter, also Melania, (known as Melanie the Younger 385- 448) to adopt a more ascetical life and to take her over her monastic baton.

We know that Melanie became the spiritual director of Evagrius Ponticus (345-400), a theologian of great influence. Undoubtedly she was most suited to be a spiritual director. Palladius tells us "She was most erudite and fond of literature, and she turned night into day going through every writing of the ancient commentators three million lines of Origen, and half a million lines of Gregory, Stephen, Pieius, Basil and other worthy men. And she did not read them once only or in an off hand way, but she worked on them, dredging through each book seven or eight times." Indeed "no one failed to benefit by her good works, neither in the east or west, neither in the north or south, For thirty-seven years she practiced hospitality; from her own treasury she made donations to churches, monasteries, guests and prisons."

A nun, Egeria, probably from Aquitania, visited the Holy Land between 381- 384 i.e. during the time of Melanie the Elder. As well as knowing she belonged to a religious community, and steeped in knowledge of Scripture, she also left a detailed account of how Lent and Holy Week were celebrated during this time when Cyril was bishop of Jerusalem.

Melanie the Younger's life followed basically the same pattern as the other women. Of patrician birth, wealthy, she married at fourteen. After the death of their second child (stillborn), she made her husband promise to live a life of chastity with her. They thus became partners in this ascetic journey. At first they helped the poor and imprisoned and those in debt, followed by giving away their Roman possessions and endowing monasteries for men and women. With the invasion of Rome (410), they with her mother, Albina, settled near Thagaste to be near Alypius, the local bishop, the friend of Augustine. Finally they began to live the ascetic life after building a double monastery. As well as being in charge of the nuns, Melanie copied the Old and New Testament, recited the Offices by heart, and devoured all books which came into reach, whether in Greek or Latin. After seven years they moved to Jerusalem, and after brief tour of the Egyptian desert, settled permanently there. Here she lived the ascetic life for another 14 years until her mother's death. Her mother's remains were brought to the monastery on Mt. Olives, and she had a monastery built for herself, virgins, and "women from places of ill-repute" in 432. This monastery housed ninety women, and after Pinian's death (her husband) she built a chapel, church and a monastery for men in 436. The women chanted the Office at the third, sixth, and ninth hours, evening and the middle of the night, just as Paula's nuns had. On feasts and Sundays they would chant extra verses. The women attended Mass on Fridays and Sundays in the Oratory. Fasting was up to the discretion of each person, because of all virtues this was regarded as the least important. But obedience was exalted as "the great possession", and given not only to the Superior but also to each other.

Melanie the Younger's life followed basically the same pattern as the other women. Of patrician birth, wealthy, she married at fourteen. After the death of their second child (stillborn), she made her husband promise to live a life of chastity with her. They thus became partners in this ascetic journey. At first they helped the poor and imprisoned and those in debt, followed by giving away their Roman possessions and endowing monasteries for men and women. With the invasion of Rome (410), they with her mother, Albina, settled near Thagaste to be near Alypius, the local bishop, the friend of Augustine. Finally they began to live the ascetic life after building a double monastery. As well as being in charge of the nuns, Melanie copied the Old and New Testament, recited the Offices by heart, and devoured all books which came into reach, whether in Greek or Latin. After seven years they moved to Jerusalem, and after brief tour of the Egyptian desert, settled permanently there. Here she lived the ascetic life for another 14 years until her mother's death. Her mother's remains were brought to the monastery on Mt. Olives, and she had a monastery built for herself, virgins, and "women from places of ill-repute" in 432. This monastery housed ninety women, and after Pinian's death (her husband) she built a chapel, church and a monastery for men in 436. The women chanted the Office at the third, sixth, and ninth hours, evening and the middle of the night, just as Paula's nuns had. On feasts and Sundays they would chant extra verses. The women attended Mass on Fridays and Sundays in the Oratory. Fasting was up to the discretion of each person, because of all virtues this was regarded as the least important. But obedience was exalted as "the great possession", and given not only to the Superior but also to each other.

Melanie's monasteries were famous and attracted many for their piety and learning. Amongst those who visited was Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II. She referred to Melanie as "my Mother".

Melanie's monasteries were famous and attracted many for their piety and learning. Amongst those who visited was Eudocia, the wife of Theodosius II. She referred to Melanie as "my Mother".

The fall of Rome by the Vandals, Huns and Goths in 410 saw the beginning of one wave of invasion of another throughout Europe. In the midst of all this the only constancy was the life of the Church. Walls of monasteries provided security. So throughout Europe many monasteries were established. For example, Cassian and his sister established a double monastery in Marseilles c.416; Honoratus and his sister Margaret established another at Lérins. Thus in this time of ravaging by different armies the monastic life was particularly attractive to women where they were safe from rape, murder and plunder under the rule of the abbess. Yet their prayers and acts of charity did untold good in an unstable time.

The fall of Rome by the Vandals, Huns and Goths in 410 saw the beginning of one wave of invasion of another throughout Europe. In the midst of all this the only constancy was the life of the Church. Walls of monasteries provided security. So throughout Europe many monasteries were established. For example, Cassian and his sister established a double monastery in Marseilles c.416; Honoratus and his sister Margaret established another at Lérins. Thus in this time of ravaging by different armies the monastic life was particularly attractive to women where they were safe from rape, murder and plunder under the rule of the abbess. Yet their prayers and acts of charity did untold good in an unstable time.

Most of these women have gone unnoticed but there are some who have come down to us by various means. One is Eustadolia of Bourges. She is mentioned in the biography of her patron Bishop Sulpicius, as a worker of miracles. For instance at a time of drought, she and her woman companions walked in procession to the church to pray for rain. They barely reached their home before the heavens opened.

Most of these women have gone unnoticed but there are some who have come down to us by various means. One is Eustadolia of Bourges. She is mentioned in the biography of her patron Bishop Sulpicius, as a worker of miracles. For instance at a time of drought, she and her woman companions walked in procession to the church to pray for rain. They barely reached their home before the heavens opened.

Genovefa of Paris had been singled out by Bishop Germanus of Auxerre whilst still a child and consecrated her life to God. As a young adult she and others took the veil but did they did not form a regular community. Her most celebrated deed was to protect Paris from the Huns by a wall of continuous prayer. As Childeric was seiging Paris she persuaded him to let her sail up the Seine to collect food for the city, and then to be able to distribute it, especially to the very poor and helpless. She travelled tirelessly around the Parisian countryside, healing the sick, routing demons and freeing prisoners. It was said than when Childeric wanted to execute some prisoners in the city, he closed the gates to prevent Genovefa from saving them. Undeterred this holy virgin pushed aside the heavy barriers and saved the captives.

Genovefa of Paris had been singled out by Bishop Germanus of Auxerre whilst still a child and consecrated her life to God. As a young adult she and others took the veil but did they did not form a regular community. Her most celebrated deed was to protect Paris from the Huns by a wall of continuous prayer. As Childeric was seiging Paris she persuaded him to let her sail up the Seine to collect food for the city, and then to be able to distribute it, especially to the very poor and helpless. She travelled tirelessly around the Parisian countryside, healing the sick, routing demons and freeing prisoners. It was said than when Childeric wanted to execute some prisoners in the city, he closed the gates to prevent Genovefa from saving them. Undeterred this holy virgin pushed aside the heavy barriers and saved the captives.

Childeric's own daughter-in-law, Queen Clothhild, was a remarkable woman of any account, who founded houses at Tours and Les Andelys. Her daughter-in-law, Radegund, had as a child taught herself the rudiments of the religious life, and after she became Queen, she sought instruction in asceticism from local hermits. Although a princess by birth she had been forced to marry the heathen Clothar, after he had ransacked her home- town of Thuringia even though he already had four wives. After her husband killed her brother, she was determined to escape. Withdrawing to Noyon on the pretext of some religious observance, she was successful in escaping to the bishop of Soissons who ordained her as a deaconess. She then escaped from her husband's territory to the sanctuary of St. Martin of Tours, and thence to St. Hilary's at Poitiers. Here she founded her monastery within a mile or two of the city, Sainte-Croix of Poitiers (Holy Cross) where she adopted the Rule for Nuns that Caesarius of Arles had written for her sister, Caesaria, who had learnt what she should teach at the monastery of Holy Saviour, Marseilles.

Childeric's own daughter-in-law, Queen Clothhild, was a remarkable woman of any account, who founded houses at Tours and Les Andelys. Her daughter-in-law, Radegund, had as a child taught herself the rudiments of the religious life, and after she became Queen, she sought instruction in asceticism from local hermits. Although a princess by birth she had been forced to marry the heathen Clothar, after he had ransacked her home- town of Thuringia even though he already had four wives. After her husband killed her brother, she was determined to escape. Withdrawing to Noyon on the pretext of some religious observance, she was successful in escaping to the bishop of Soissons who ordained her as a deaconess. She then escaped from her husband's territory to the sanctuary of St. Martin of Tours, and thence to St. Hilary's at Poitiers. Here she founded her monastery within a mile or two of the city, Sainte-Croix of Poitiers (Holy Cross) where she adopted the Rule for Nuns that Caesarius of Arles had written for her sister, Caesaria, who had learnt what she should teach at the monastery of Holy Saviour, Marseilles.

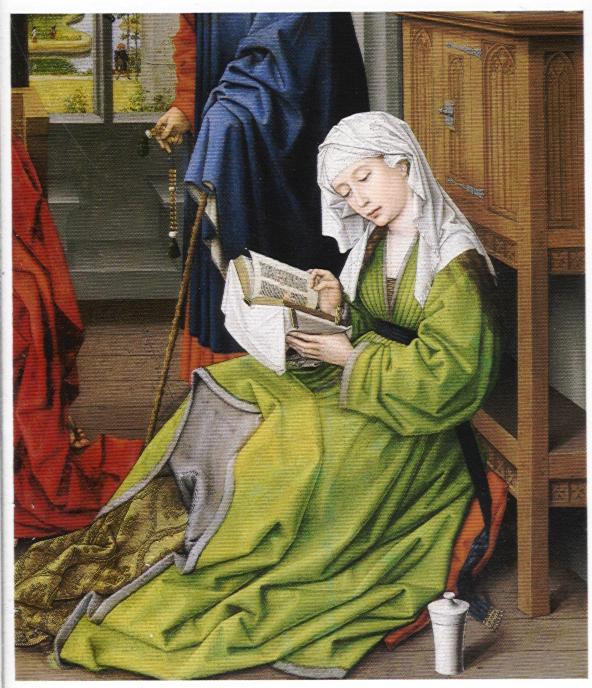

This Rule by Caesarius is the first written monastic rule, exclusively for women which has survived. It demanded strict enclosure and a high degree of literacy. "Let there be no sister entering who does not know letters", wrote Abbess Caesaria to Radegund in 567. Several hours each day were to be dedicated to the study and writing of scripture, and tasks requiring knowledgeable and disciplined minds. Books were so essential to their life that there was a librarian in the community. On entering the convent nuns made a solemn promise to remain until death.

This Rule by Caesarius is the first written monastic rule, exclusively for women which has survived. It demanded strict enclosure and a high degree of literacy. "Let there be no sister entering who does not know letters", wrote Abbess Caesaria to Radegund in 567. Several hours each day were to be dedicated to the study and writing of scripture, and tasks requiring knowledgeable and disciplined minds. Books were so essential to their life that there was a librarian in the community. On entering the convent nuns made a solemn promise to remain until death.

The convent furniture was to be the simplest, and no paintings were allowed. Bedrooms were communal. Spinning of wool, making their own garments, caring for the monastery apart from prayer and meditation were to be the main industry of nuns. Recitation of the Office was to occupy them for most of the day. Discipline was enforced and obedience demanded. This monastery also maintained a school for girls six years and older. However the abbess and her nuns were exempt by the Pope from all episcopal authority, and so the community administered to its own need. A bishop could only enter when requested for pastoral needs.

The convent furniture was to be the simplest, and no paintings were allowed. Bedrooms were communal. Spinning of wool, making their own garments, caring for the monastery apart from prayer and meditation were to be the main industry of nuns. Recitation of the Office was to occupy them for most of the day. Discipline was enforced and obedience demanded. This monastery also maintained a school for girls six years and older. However the abbess and her nuns were exempt by the Pope from all episcopal authority, and so the community administered to its own need. A bishop could only enter when requested for pastoral needs.

Radegund never became abbess of her monastery, and she herself lived in a hermit attached to the monastery. Nevertheless she participated fully in the daily work of the community. She took her turn in the kitchen, carrying wood and water, cleaning the latrines, and polishing the nun's shoes. She expounded the Scriptures and instructed the nuns in the life of prayer. She was a peace maker and insisted on peace in the monastery, even the singing of birds was not encouraged. She organised a huge relic collection, including a relic of the true cross from Constantinople. She cared for guests by washing their feet, providing fresh bedding, preparing food and liturgy.

Radegund never became abbess of her monastery, and she herself lived in a hermit attached to the monastery. Nevertheless she participated fully in the daily work of the community. She took her turn in the kitchen, carrying wood and water, cleaning the latrines, and polishing the nun's shoes. She expounded the Scriptures and instructed the nuns in the life of prayer. She was a peace maker and insisted on peace in the monastery, even the singing of birds was not encouraged. She organised a huge relic collection, including a relic of the true cross from Constantinople. She cared for guests by washing their feet, providing fresh bedding, preparing food and liturgy.

When she died in 587 there were over 200 nuns at Poitiers. When Gregory of Tours arrived to perform the funeral rites the community was ravaged with grief. They expressed their loss in glowing terms.

When she died in 587 there were over 200 nuns at Poitiers. When Gregory of Tours arrived to perform the funeral rites the community was ravaged with grief. They expressed their loss in glowing terms.

We gave up our parents and friends and country to follow you. Here we found gold and silver; here we knew flowering vines and leafy plants; here were fields flowering with riotous blossom. From you we took violets: you were the blushing rose and the white lily. You spoke in words bright as the sun, as and as the moon against the darkness, you burned as a lamp with the light of truth. But now, it is all darkness with us.

We gave up our parents and friends and country to follow you. Here we found gold and silver; here we knew flowering vines and leafy plants; here were fields flowering with riotous blossom. From you we took violets: you were the blushing rose and the white lily. You spoke in words bright as the sun, as and as the moon against the darkness, you burned as a lamp with the light of truth. But now, it is all darkness with us.

Just as Thecla had been the model for virgins in the East, so Radegund became the model for all nuns in the West.

Just as Thecla had been the model for virgins in the East, so Radegund became the model for all nuns in the West.

As monasteries for women amongst the Germanics were sealed off from the outside the world, mainly to preserve them from attack and to safeguard the women, the ascetic life became associated with walled enclosures rather than caves or huts. Another feature of these enclosed houses was the communal aspect, both in prayer, activity and meal time. Radegund's contemporary, Benedict, who is known as the Father of Monasticism certainly emphasised the communal aspect of monastic life, as well as obedience to one's particular abbot and community.

As monasteries for women amongst the Germanics were sealed off from the outside the world, mainly to preserve them from attack and to safeguard the women, the ascetic life became associated with walled enclosures rather than caves or huts. Another feature of these enclosed houses was the communal aspect, both in prayer, activity and meal time. Radegund's contemporary, Benedict, who is known as the Father of Monasticism certainly emphasised the communal aspect of monastic life, as well as obedience to one's particular abbot and community.

Benedict had a sister, Scholastica who had consecrated her life to Christ at a very early age. After Benedict built his famous monastery at Monte Cassino, Scholastica moved to Plombariola, five miles away where she founded a monastery and ruled her nuns, presumably along the lines of her brother's rule as she is still highly honoured in Benedictine's communities throughout the world. What Scholastica organised for her community soon became the monastic way for women, just as her brother's for men. Indeed nothing so much dominated mediaeval history as did the Benedictines.

Benedict had a sister, Scholastica who had consecrated her life to Christ at a very early age. After Benedict built his famous monastery at Monte Cassino, Scholastica moved to Plombariola, five miles away where she founded a monastery and ruled her nuns, presumably along the lines of her brother's rule as she is still highly honoured in Benedictine's communities throughout the world. What Scholastica organised for her community soon became the monastic way for women, just as her brother's for men. Indeed nothing so much dominated mediaeval history as did the Benedictines.

Brief look at the Benedictine rule

There were seventy-three chapters in the Benedictine Rule, of which the oldest surviving copy is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Nine treat the duties of the abbot/abbess, thirteen regulate the worship of God, twenty-nine set out the discipline and penal code, ten are concerned with internal administration, and the other twelve with miscellaneous regulations.

There were seventy-three chapters in the Benedictine Rule, of which the oldest surviving copy is in the Bodleian Library, Oxford. Nine treat the duties of the abbot/abbess, thirteen regulate the worship of God, twenty-nine set out the discipline and penal code, ten are concerned with internal administration, and the other twelve with miscellaneous regulations.

Benedict adopted a sensible and sensitive approach for his Rule or what he called it "a little rule for beginners" [the great rule for Benedict was the Holy Scriptures]; there was to be "nothing harsh, nothing burdensome". For Benedict living the monastic and indeed the Christian life was not to be handicapped with austerities and hurdles, which so often crushed the essence of true devotion. In fact his rule is a rule that every Christian can live by, even in to-day's world as it envisaged a life balanced between prayer and work. Monks spent time praying in order to discover why they worked, and they spent time working so that good order and harmony would prevail in the monastery. Hence all monks from the youngest to the most educated had to be engaged in some manual work every day. From this concept the great Benedictine motto was established Laborare est orare. So the goal of the Benedictine day was to make the monk/nun conscious of the presence of God through the entire day.

Benedict adopted a sensible and sensitive approach for his Rule or what he called it "a little rule for beginners" [the great rule for Benedict was the Holy Scriptures]; there was to be "nothing harsh, nothing burdensome". For Benedict living the monastic and indeed the Christian life was not to be handicapped with austerities and hurdles, which so often crushed the essence of true devotion. In fact his rule is a rule that every Christian can live by, even in to-day's world as it envisaged a life balanced between prayer and work. Monks spent time praying in order to discover why they worked, and they spent time working so that good order and harmony would prevail in the monastery. Hence all monks from the youngest to the most educated had to be engaged in some manual work every day. From this concept the great Benedictine motto was established Laborare est orare. So the goal of the Benedictine day was to make the monk/nun conscious of the presence of God through the entire day.

However the great work was Opus Dei, the singing of the Daily Offices.

However the great work was Opus Dei, the singing of the Daily Offices.

The role of monasteries of women in the Dark Ages was not dissimilar to the house-church of early Christianity. It served spiritual, educational and healing needs as well as acting as "safe house" and providing what we call to-day social services.

The role of monasteries of women in the Dark Ages was not dissimilar to the house-church of early Christianity. It served spiritual, educational and healing needs as well as acting as "safe house" and providing what we call to-day social services.

Young women as well as widows were attracted to the life of the convent. Even 12 year olds sought admission. On profession nuns took the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. At its best the life of the convent produced a prayerful round of work: liturgy, prayer, meditation especially on the Scriptures and study. It also had its own bakery, farm, brewery, scriptoria, and guest- house. It was like a mini-town.

Young women as well as widows were attracted to the life of the convent. Even 12 year olds sought admission. On profession nuns took the vows of poverty, chastity and obedience. At its best the life of the convent produced a prayerful round of work: liturgy, prayer, meditation especially on the Scriptures and study. It also had its own bakery, farm, brewery, scriptoria, and guest- house. It was like a mini-town.

Meanwhile in the Eastern Church roots were also being made in the monastic life. One of the women involved was a renowned wealthy widow, Olympias, who was ordained a deaconess. She formed part of the inner circle around the famous John Chrysostom who indeed was supported by her during his many exiles. He praised Olympias for being a tower of strength "without thrusting yourself into the forum or occupying public centres of the city". Indeed the circle of Chrysostom included many deaconesses.

Meanwhile in the Eastern Church roots were also being made in the monastic life. One of the women involved was a renowned wealthy widow, Olympias, who was ordained a deaconess. She formed part of the inner circle around the famous John Chrysostom who indeed was supported by her during his many exiles. He praised Olympias for being a tower of strength "without thrusting yourself into the forum or occupying public centres of the city". Indeed the circle of Chrysostom included many deaconesses.

Olympias also founded the first community next to the episcopal palace (Olympiados). The first members were her servants and slaves, but it soon attracted other women. John himself placed numerous widows and nuns under her care. These women also supported Chrysostom in his struggle against the Empress, Eudocia. Olympias established a hospital and an orphanage, and gave shelter to the expelled orthodox monks of Nitria. But her friendship with John cost her dearly. Her communities had to be disbanded, and she also had to go into exile.

Olympias also founded the first community next to the episcopal palace (Olympiados). The first members were her servants and slaves, but it soon attracted other women. John himself placed numerous widows and nuns under her care. These women also supported Chrysostom in his struggle against the Empress, Eudocia. Olympias established a hospital and an orphanage, and gave shelter to the expelled orthodox monks of Nitria. But her friendship with John cost her dearly. Her communities had to be disbanded, and she also had to go into exile.

More famous than Olympias in the Eastern Church for the beginning of monasticism was Macrina, the sister of Basil and Gregory of Nyssa. Her virginity had been saved after her betrothed died. From that moment on she was determined that the whole household would live under monastic regulations. She made no secret that her model was Thecla and she had been well taught by her mother, Emmelia. As a result she founded a double monastery, separated by a river, with her brother Peter head of the men, and herself in charge of the women. Actually the family home was made the convent. By the time she died her convent housed many women, and Macrina was much loved. She was well known for her hospitality and charity. Indeed she was an outstanding woman, equally brilliant as her famous brothers, as philosopher, teacher, and scripture scholar.

More famous than Olympias in the Eastern Church for the beginning of monasticism was Macrina, the sister of Basil and Gregory of Nyssa. Her virginity had been saved after her betrothed died. From that moment on she was determined that the whole household would live under monastic regulations. She made no secret that her model was Thecla and she had been well taught by her mother, Emmelia. As a result she founded a double monastery, separated by a river, with her brother Peter head of the men, and herself in charge of the women. Actually the family home was made the convent. By the time she died her convent housed many women, and Macrina was much loved. She was well known for her hospitality and charity. Indeed she was an outstanding woman, equally brilliant as her famous brothers, as philosopher, teacher, and scripture scholar.

Over the seas in Ireland a young virgin was responding to the preaching of Patrick, Bridget/Brigid of Kildare. Patrick's life had been inspired by the Life of Antony, and so his monasticism, was based on the earliest desert tradition, where women had a relatively equal footing with men, and hence the many double monastery in Ireland and other Celtic places.

Over the seas in Ireland a young virgin was responding to the preaching of Patrick, Bridget/Brigid of Kildare. Patrick's life had been inspired by the Life of Antony, and so his monasticism, was based on the earliest desert tradition, where women had a relatively equal footing with men, and hence the many double monastery in Ireland and other Celtic places.

Bridget was born about a century after Marcella and Paula had established their Christians communities in Rome, that is, c.450. She was born into a Druid family, being the daughter of Dubhthach, court poet to King Loeghaire in Fochard, County Louth. At an early age, she decided to become a Christian, and it is said she received the Veil from St. Patrick when only 14 years old. Another tradition stated she received the Veil from St. Macaille. With seven other virgins she settled for a time at the foot of Croghan Hill, but then removed to Druin Criadh, in the plains of Magh Life, where under a large oak tree she erected her subsequently famous Convent of Cill-Dara, that is, "the church of the oak" (now Kildare), in the present county of that name. She was later joined by a community of monks led by Conlaed.

Bridget was born about a century after Marcella and Paula had established their Christians communities in Rome, that is, c.450. She was born into a Druid family, being the daughter of Dubhthach, court poet to King Loeghaire in Fochard, County Louth. At an early age, she decided to become a Christian, and it is said she received the Veil from St. Patrick when only 14 years old. Another tradition stated she received the Veil from St. Macaille. With seven other virgins she settled for a time at the foot of Croghan Hill, but then removed to Druin Criadh, in the plains of Magh Life, where under a large oak tree she erected her subsequently famous Convent of Cill-Dara, that is, "the church of the oak" (now Kildare), in the present county of that name. She was later joined by a community of monks led by Conlaed.

Kildare had formerly been a pagan shrine where a sacred fire was kept perpetually burning, and Bridget and her nuns, instead of stamping out the fire, kept it going but gave it a Christian interpretation. (This was in keeping with the general process whereby Druidism in Ireland gave way to Christianity with very little opposition, the Druids for the most part saying that their own beliefs were a partial and tentative insight into the nature of God, and that they recognized in Christianity what they had been looking for.) Bridget as an abbess participated in several Irish councils, and her influence on the policies of the Church in Ireland was considerable. There is a legend that Ibor consecrated her as a bishop, and that was why she became such an influential abbess. She certainly travelled constantly founding other monasteries.

Kildare had formerly been a pagan shrine where a sacred fire was kept perpetually burning, and Bridget and her nuns, instead of stamping out the fire, kept it going but gave it a Christian interpretation. (This was in keeping with the general process whereby Druidism in Ireland gave way to Christianity with very little opposition, the Druids for the most part saying that their own beliefs were a partial and tentative insight into the nature of God, and that they recognized in Christianity what they had been looking for.) Bridget as an abbess participated in several Irish councils, and her influence on the policies of the Church in Ireland was considerable. There is a legend that Ibor consecrated her as a bishop, and that was why she became such an influential abbess. She certainly travelled constantly founding other monasteries.

Brigid appointed St. Conleth as spiritual pastor to the monastics. Her biographer tells us distinctly that she chose St. Conleth "to govern the church along with herself". Thus, for centuries, Kildare was ruled by a double line of abbot-bishops and of abbesses, the Abbess of Kildare being regarded as superioress general of the convents in Ireland.

Brigid appointed St. Conleth as spiritual pastor to the monastics. Her biographer tells us distinctly that she chose St. Conleth "to govern the church along with herself". Thus, for centuries, Kildare was ruled by a double line of abbot-bishops and of abbesses, the Abbess of Kildare being regarded as superioress general of the convents in Ireland.

Brigid also founded a school of art, including metal work and illumination, over which St. Conleth presided. From the Kildare scriptorium came the wondrous book of the Gospels, which elicited unbounded praise from Giraldus Cambrensis, but which has disappeared since the Reformation. According to this twelfth- century ecclesiastic, nothing that he had ever seen was at all comparable to the Book of Kildare, every page of which was gorgeously illuminated, and he concluded on a most laudatory notice by saying that the interlaced work and the harmony of the colours left the impression that "all this is the work of angelic, and not human skill". It has been suggested that this book was written night after night as St. Bridget prayed, "an angel furnishing the designs, the scribe copying". Even allowing for the exaggerated stories told of St. Brigid by her numerous biographers, it is certain that she ranks as one of the most remarkable Irishwomen of the fifth century and as the Patroness of Ireland. She is lovingly called the "Queen of the South: the Mary of the Gael" by a writer in the "Leabhar Breac". St. Brigid died leaving a cathedral city and school that became famous all over Europe.

Brigid also founded a school of art, including metal work and illumination, over which St. Conleth presided. From the Kildare scriptorium came the wondrous book of the Gospels, which elicited unbounded praise from Giraldus Cambrensis, but which has disappeared since the Reformation. According to this twelfth- century ecclesiastic, nothing that he had ever seen was at all comparable to the Book of Kildare, every page of which was gorgeously illuminated, and he concluded on a most laudatory notice by saying that the interlaced work and the harmony of the colours left the impression that "all this is the work of angelic, and not human skill". It has been suggested that this book was written night after night as St. Bridget prayed, "an angel furnishing the designs, the scribe copying". Even allowing for the exaggerated stories told of St. Brigid by her numerous biographers, it is certain that she ranks as one of the most remarkable Irishwomen of the fifth century and as the Patroness of Ireland. She is lovingly called the "Queen of the South: the Mary of the Gael" by a writer in the "Leabhar Breac". St. Brigid died leaving a cathedral city and school that became famous all over Europe.