Women were from the beginning amongst those who suffered for their faith as evidenced in Saul's campaign against Christians (Acts.9.2). How many were killed by Saul we shall never know. During Nero's reign a conflagration razed much of Rome, said to have been started by the emperor himself, but to divert attention from himself he blamed Christians for the fire in Rome. Many were rounded up, including women, and tortured and killed some twenty years after Saul's persecution. Amongst those martyred were the apostles, Paul and Peter. Being the scapegoat for the fire of Rome brought attention to those who followed Christ and their adherence to Him being the only true God. From Nero until the recognition of Christianity by the Emperor Constantine in A. D.313 there were spasmodic severe persecutions of Christians for 250 years.

Why were Christians persecuted in the Roman Empire? After Augustus' death in A.D.14 he was declared divine, and shrines commemorating his divinity were built. After him all emperors were recognised as being divine, and some emperors would attach greater importance to being worshipped as a god. Apart from the emperor being regarded as a god, the Romans had many pagan gods, and not to give them homage meant invoking disapproval too.

Why were Christians persecuted in the Roman Empire? After Augustus' death in A.D.14 he was declared divine, and shrines commemorating his divinity were built. After him all emperors were recognised as being divine, and some emperors would attach greater importance to being worshipped as a god. Apart from the emperor being regarded as a god, the Romans had many pagan gods, and not to give them homage meant invoking disapproval too.

When Christianity began it was seen as a sect within Judaism, but before too long Christians were bringing attention to themselves by their aloofness, and "secret" activities. There were tales of "eating flesh" and other abnormal behaviour. Their aloofness, brought criticism of their anti-social behaviour, and when things went wrong, Christians began to be singled out as the culprits because they did not worship the gods. Writing in about A.D. 196, Tertullian said, "The Christians are to blame for every public disaster and every misfortune that befalls the people. If the Tiber rises to the walls, if the Nile fails to rise and flood the fields, if the sky withholds its rain, if there is earthquake or famine or plague, straightway the cry arises: 'The Christians to the lions!'"

Christians were sometimes hauled before the authorities and asked to offer incense to the Emperor. Of course for Christians this was blasphemy, and they refused to do so. This often led to Christians being sentenced to death, as for example during the reign of Emperor Decius when he undertook to restore the old Roman spirit. In A.D. 250 he published an edict calling for a return to the pagan state religion. Local commissioners were appointed to enforce the ruling. Before him, under Septimius Severus in A.D.202 a law prohibiting the spread of Christianity and Judaism was enacted. This was the first universal decree forbidding conversion to Christianity.

Christians were sometimes hauled before the authorities and asked to offer incense to the Emperor. Of course for Christians this was blasphemy, and they refused to do so. This often led to Christians being sentenced to death, as for example during the reign of Emperor Decius when he undertook to restore the old Roman spirit. In A.D. 250 he published an edict calling for a return to the pagan state religion. Local commissioners were appointed to enforce the ruling. Before him, under Septimius Severus in A.D.202 a law prohibiting the spread of Christianity and Judaism was enacted. This was the first universal decree forbidding conversion to Christianity.

The earliest secular extant account of Christian women suffering for their faith was given by Tacitus in his Annales (9.3.32) written in A.D. 57, about the same time that Paul wrote his first letter to the Corinthians, and by Pliny the Younger in his famous letter to Trajan c.112 (Epp.x.xcvi). Tacticus described the trial of Pomponia Graecina, a woman of high rank, who was accused of "foreign superstition" and handed over to her husband as judge for her trial. This woman was the first Christian persecuted for the faith that history records outside the New Testament.

Pliny the Younger wrote "I thought it the more necessary, therefore, to find out what truth there was in this (accusation against Christians) by applying torture to two maidservants who were called ministers. But I found nothing but a depraved and extravagant superstition." [Pliny, Epp.X (at Trajan) xcvi] These women, who may well have been quite young, were probably slaves since they were called maidservants. Yet they were recognized publicly as Christian ministers (Latin "ministrae", lit. "female ministers"). Their witness for Christ must have been public, for they were arrested and tortured to incriminate the rest of the church.

Pliny the Younger wrote "I thought it the more necessary, therefore, to find out what truth there was in this (accusation against Christians) by applying torture to two maidservants who were called ministers. But I found nothing but a depraved and extravagant superstition." [Pliny, Epp.X (at Trajan) xcvi] These women, who may well have been quite young, were probably slaves since they were called maidservants. Yet they were recognized publicly as Christian ministers (Latin "ministrae", lit. "female ministers"). Their witness for Christ must have been public, for they were arrested and tortured to incriminate the rest of the church.

Before the end of 1st century. A.D. Clement, presbyter of Rome, wrote in his Stromateus that Peter's wife was martyred before him in Rome during Nero's persecution. Clement related "that the blessed Peter, seeing his own wife led away to execution, was delighted on account of her calling and return to her country, and that he cried to her in a consolatory and encouraging voice, addressing her by name: 'Oh thou, remember, the Lord!' Such was the marriage of these blessed ones, and such was their perfect affection towards their dearest friends."

Eusebius writing his Ecclesiastical History in the 4th cwntury mentioned of another high rank woman suffering for her faith during the time of the persecution of Domitian c.93. "At the same time, for professing Christ, Flavia Domatilla, the niece of Flavius Clemens, one of the consuls of Rome at that time, was transported with many others, by way of punishment, to the island of Pontia." (Book 2, ch. XVIII) This was during the persecution of Domitian when the apostle John was supposedly exiled to Patmos, c. A.D. 93.

He also mentioned martyrdoms at Pergamus c. A.D.155, about the same time of Polycarp's martyrdom. "Of these we mention only Carpus and Papylus, and a woman named Agathonice; who, after many and illustrious testimonies given by them, gloriously finished their course." (Book 4, ch XV)

Another early feminine martyred is Saint Eudicia Heliopolis, an infamous and wealthy prostitute. One night she overheard a monk chanting his prayers and reciting aloud the Gospel reciting of Christ judging the world (Mt. 25, 31 - 46). Stung with her remorse for her sins, she sought instruction in the Christian faith and was baptized. Having given away her enormous riches to the poor, Eudocia became the superior of a desert community of consecrated women. Upon the order of the Roman authorities, she was martyred by beheading in A. D. 152.

One of the worst persecutions Christians faced in those early centuries occurred in Gaul under the reign of Marcus Aurelius (A.D. 161-180). In the year 177 persecution occurred in the province of Gaul in Vienne, near Lyons, and the bishop himself was sentenced to death (St. Pothinus). Fortunately for us we know much about this persecution from a letter written by those Christians who survived to the church in Asia and Phrygia.

"But the whole wrath of the populace, and governor, and soldiers was aroused exceedingly against Sanctus, the deacon from Vienne, and Maturus, a late convert, yet a noble combatant, and against Attalus, a native of Pergamos where he had always been a pillar and foundation, and Blandina, through whom Christ showed that things which appear mean and obscure and despicable to men are with God of great glory, through love toward him manifested in power, and not boasting in appearance."

Eusebius in Book V, Ch. 1 has preserved this account. Of all who suffered it was Blandina who was the recognized leader, a spiritual mother, inspiring others in prayer and courage to remain steadfast to Christ. Indeed it is said she was "like a noble mother encouraging her children. In the manner of her death she was the image of the crucified Christ, as she hanged from a post with her arms outstretched. Blandina may have been "tiny, weak and insignificant" but "she had put on Christ that mighty and invincible athlete." In her death Blandina had shown "that the things that men think cheap, ugly and contemptuous are deemed worthy of glory before God."

Eusebius in Book V, Ch. 1 has preserved this account. Of all who suffered it was Blandina who was the recognized leader, a spiritual mother, inspiring others in prayer and courage to remain steadfast to Christ. Indeed it is said she was "like a noble mother encouraging her children. In the manner of her death she was the image of the crucified Christ, as she hanged from a post with her arms outstretched. Blandina may have been "tiny, weak and insignificant" but "she had put on Christ that mighty and invincible athlete." In her death Blandina had shown "that the things that men think cheap, ugly and contemptuous are deemed worthy of glory before God."

Not long after the persecution in Vienne, in the opening years of the 3rd century, severe persecution occurred in North Africa under the emperor Severus. The two notable martyrs were like Blandina, young women, Perpetua and her slave-girl, Felicitas. Again we know so much of this persecution through Perpetua's diary, which gives an account of hers and other Christians' imprisonment before their martyrdom. Indeed the Passion of Perpetua and Felicitas is the earliest writing of a Christian woman. The martyrdoms of Perpetua and her slave woman were even the more extraordinary as the mistress was still breastfeeding her baby whilst the servant gave birth just prior to martyrdom. So we hear of the pains of childbirth endured by Felicity, and the breasts of Perpetua aching from unused milk after her baby was taken from her in prison. Their stories are about women and their bodies and the violation of these bodies in the course of imprisonment and execution. As with the account of Blandina's death, the torturous bodies of these two women carry enormous significance for the early Christian community, and hence the accounts of their martyrs' deaths were told over and over again by Christians, mainly by letters for encouragement and example. These accounts emphasised the sufferings of Christ joining with those of the martyrs in their death, who achieved instant union with Christ in heaven.

What set Perpetua and Felicity apart from other women saints in the early church was that both were mothers and wives. There were plenty of virgins willing to cling to their true spouse Christ in suffering, but a young mother was something else. Both Perpetua and Felicitas lived in the North African city of Carthage and together with their teacher, Saturus, as well as three others, Revocatus, Saturninus and Secundulus, were catechumens. Yet it was apparent that amongst this group of Christians facing persecution, Perpetua was the leader.

What set Perpetua and Felicity apart from other women saints in the early church was that both were mothers and wives. There were plenty of virgins willing to cling to their true spouse Christ in suffering, but a young mother was something else. Both Perpetua and Felicitas lived in the North African city of Carthage and together with their teacher, Saturus, as well as three others, Revocatus, Saturninus and Secundulus, were catechumens. Yet it was apparent that amongst this group of Christians facing persecution, Perpetua was the leader.

Like the martyrs at Vienne we also know the details of the martyrdom in Carthage firstly through the diary of Perpetua herself, and its completion by an eyewitness of her martyrdom and the others. Thus through "The Passion of Holy Women" we learn of her leadership in prison; her demands for better treatment and conditions for the prisoners; her love for her own baby, the birth-pains of her slave, Felicitas; her relationship with her father; her own preparation for death; her baptism; and the dreams she has to verify that she will indeed be martyred in a cruel way.

Like the martyrs at Vienne we also know the details of the martyrdom in Carthage firstly through the diary of Perpetua herself, and its completion by an eyewitness of her martyrdom and the others. Thus through "The Passion of Holy Women" we learn of her leadership in prison; her demands for better treatment and conditions for the prisoners; her love for her own baby, the birth-pains of her slave, Felicitas; her relationship with her father; her own preparation for death; her baptism; and the dreams she has to verify that she will indeed be martyred in a cruel way.

Her meetings with her father are very vivid as her tries to save her from death, but Perpetua explained that it is God who now rules her life. He in turn told Perpetua, she was his favourite child, and addresses her in an unprecedented way, as 'lady', domina.

Perpetua's baptism is significant in more than one way. In making her a Christian it gave her a sense of authority to act for her fellow prisoners. Thus she demands better conditions in prison for them, and she became their spokesman. It also gave her the strength to meet her ordeal. As part of that she recounted four dreams of ladders and dragons, heavenly gardens and good shepherds and cool refreshing waters. Through these dreams, she experiences the healing of all her relationships with her old family and the beginning of her total concentration on her new heavenly family. It is her final dream that pre-empts her martyrdom.

Perpetua's baptism is significant in more than one way. In making her a Christian it gave her a sense of authority to act for her fellow prisoners. Thus she demands better conditions in prison for them, and she became their spokesman. It also gave her the strength to meet her ordeal. As part of that she recounted four dreams of ladders and dragons, heavenly gardens and good shepherds and cool refreshing waters. Through these dreams, she experiences the healing of all her relationships with her old family and the beginning of her total concentration on her new heavenly family. It is her final dream that pre-empts her martyrdom.

She dreams that she is going to her fate in the arena, but that when her clothes are removed, she discovers herself to be a man. In antiquity, the male body was considered the norm, and the strong woman was described as 'becoming male'. (This phrase will also later used about virginal women). The act of 'becoming male' indicated that all the carnality of the woman/Eve had been left behind, and a new creature was produced. This dream convinced Perpetua that she would prevail on the morrow, when she went to meet the wild beasts in the arena.

She dreams that she is going to her fate in the arena, but that when her clothes are removed, she discovers herself to be a man. In antiquity, the male body was considered the norm, and the strong woman was described as 'becoming male'. (This phrase will also later used about virginal women). The act of 'becoming male' indicated that all the carnality of the woman/Eve had been left behind, and a new creature was produced. This dream convinced Perpetua that she would prevail on the morrow, when she went to meet the wild beasts in the arena.

Despite her dream when she is actually in the arena there is a marked touch of feminity.

Despite her dream when she is actually in the arena there is a marked touch of feminity.

Sitting down she drew back her torn tunic from her side to cover her thighs, more mindful of her modesty than her suffering. Then having asked for a pin she furthered fastened her disordered hair. For it was not seemly that a martyr should suffer with her hair dishevelled, lest she should seem to mourn in the hour of her glory.

The execution of Perpetua and her companions took place in the 'Circus', that is, in the public arena, for the entertainment of Governor Hilarian and the city of Carthage. It was the Emperor's birthday and, on this special occasion, something special was offered to the city. Yet there was an air of superiority of Perpetua and her companions. The five marched with 'gay and gracious looks' into the arena, but 'when they came within sight of Hilarian, they began to signify to him by nods and gestures: "Thou art judging us, but God shall judge thee".'

The execution of Perpetua and her companions took place in the 'Circus', that is, in the public arena, for the entertainment of Governor Hilarian and the city of Carthage. It was the Emperor's birthday and, on this special occasion, something special was offered to the city. Yet there was an air of superiority of Perpetua and her companions. The five marched with 'gay and gracious looks' into the arena, but 'when they came within sight of Hilarian, they began to signify to him by nods and gestures: "Thou art judging us, but God shall judge thee".'

Perpetua died with total dignity and, at the age of twenty-two, confounded the total power of the Roman Empire, and of the traditional male potestas over women's lives. During her time in the arena she felt herself in direct contact with God. All the cruel power of Roman imperialism was able to prevail against her in bringing about her death, but it was not able to conquer her spirit. In the end, she had to help the 'wavering hand' of the novice gladiator to find the right path for his sword because, as the editor remarks, 'so great a woman, who was feared by the unclean spirit, could not otherwise be slain except she willed'.

And what of Felicitas? Felicitas is introduced in the beginning of the story as a slave together with Revocatus. She was eight months pregnant when arrested and feared that her pregnancy would interfere with her martyrdom as 'it is against the law for women with child to be exposed for punishment.' Two days before the date for execution, all the prisoners joined together in prayer for Felicitas' safe delivery. Immediately, her birth pains started and she gave birth to a girl, 'whom one of the sisters brought up as her own daughter'. As she cried out in pain, the warders taunted her about the much greater pain which awaited her. Felicitas answered: 'Now I suffer what I suffer; but then Another will be in me who will suffer for me, because I too am to suffer for him.' Going into the arena Felicitas rejoiced about her safe delivery: she was going 'from blood to blood, from midwife to gladiator, to find in her second baptism her childbirth washing'. She was gored by a heifer and eventually dispatched with a sword.

And what of Felicitas? Felicitas is introduced in the beginning of the story as a slave together with Revocatus. She was eight months pregnant when arrested and feared that her pregnancy would interfere with her martyrdom as 'it is against the law for women with child to be exposed for punishment.' Two days before the date for execution, all the prisoners joined together in prayer for Felicitas' safe delivery. Immediately, her birth pains started and she gave birth to a girl, 'whom one of the sisters brought up as her own daughter'. As she cried out in pain, the warders taunted her about the much greater pain which awaited her. Felicitas answered: 'Now I suffer what I suffer; but then Another will be in me who will suffer for me, because I too am to suffer for him.' Going into the arena Felicitas rejoiced about her safe delivery: she was going 'from blood to blood, from midwife to gladiator, to find in her second baptism her childbirth washing'. She was gored by a heifer and eventually dispatched with a sword.

In recounting those days in prison and the martyrdom it is amazing how much the women's concern for their bodies marks the telling of the story. We hear about their food, their clothing, their breast-milk, their birthing pains, their breast-feeding. There is hardly another account from the ancient world that concentrates with such detail on women's bodies as central to their identities. All the classic conflicts of a woman's life appear in their stories: the desire and duty to please and obey the father against the absolute priority of following God; the sense of responsibility for and love of children against the harsh exigencies of martyrdom; the real fear of bodily pain and humiliation against the search for consolation and healing wherever it could be found. At the end they went towards martyrdom with 'gay and gracious looks, trembling, if at all, not with fear but with joy'.

The deaths of Blandina, Perpetua and Felicity revealed in no uncertain terms that they took on themselves the features of Christ's suffering. Could Christ be a Christa as well as Christus. The history of the Church manifested that its hierarchy did not wish this to be.

The deaths of Blandina, Perpetua and Felicity revealed in no uncertain terms that they took on themselves the features of Christ's suffering. Could Christ be a Christa as well as Christus. The history of the Church manifested that its hierarchy did not wish this to be.

Not long after these martyrdoms in Carthage, Eusebius related how in the time of Origen c. 208, still under the emperor, Severus, there was a very notable female martyr, Potamiaena whose courage, faith, and prayers as she faced death actually converted her executioner. Eusebius calls her:

"The celebrated Potamiaena. . . concerning whom many traditions are still circulated abroad among the inhabitants of the place of the innumerable conflicts she endured for the preservation of her purity and chastity, in which indeed she was eminent. For besides the perfections of her mind, she was blooming also in the maturity of personal attractions. Many things are also related of her fortitude in suffering for faith in Christ; and, at length, after horrible tortures and pains, the very relation of which makes one shudder, she was, with her mother Macella, committed to the flames. . . . Immediately receiving the sentence of condemnation, she was led away to die by Basilides, one of the officers in the army. But when the multitude attempted to assault and insult her with abusive language, he, by keeping off, restrained their insolence; exhibiting the greatest compassion and kindness to her."

"Perceiving this man's sympathy, she exhorts him to be of good cheer, for that after she was gone she would intercede for him with her Lord, and it would not be long before she would reward him for his kind deeds towards her. Saying this, she nobly sustained the issue; having boiling pitch poured over different parts of her body, gradually by little and little, from her feet up to the crown of her head. And such, then, was the conflict which this noble virgin endured. But not long after, Basilides, being urged to swear on a certain occasion by his fellow soldiers, declared that it was not lawful for him to swear at all, for he was a Christian, and this he plainly professed. At first, indeed, they thought that he was thus far only jesting, but as he constantly persevered in the assertion, he was conducted to the judge, before whom, confessing his determination, he was committed to prison. But when some of the brethren came to see him and inquired the cause of this sudden and singular resolve, he is said to have declared that Potamiaena, indeed for the three days after her martyrdom, standing before him at night, placed a crown upon his head and said that she had entreated the Lord on his account, and she had obtained her prayer, and that ere long she would take him with her. On this, the brethren gave him the seal in the Lord, and he, bearing a distinguished testimony to the Lord, was beheaded. Many others also of those at Alexandria are recorded as having promptly attached themselves to the doctrine of Christ in these times, and this by reason of Potamiaena, who appeared in dreams and exhorted many to embrace the divine word."

Those years before 313 also witnessed the death and martyrdom of many virgins: those who had consecrated themselves as a bride of Christ rather than be subjected to marriage. Paul's teaching on virginity struck a chord with women very quickly in the early church. Hence there are many examples of young women who saw Christ as their spouse and thus refused betrothals. This often brought them into conflict with either their fathers or the betrothed who out of spite often handed them over to the local Roman authorities.

Those years before 313 also witnessed the death and martyrdom of many virgins: those who had consecrated themselves as a bride of Christ rather than be subjected to marriage. Paul's teaching on virginity struck a chord with women very quickly in the early church. Hence there are many examples of young women who saw Christ as their spouse and thus refused betrothals. This often brought them into conflict with either their fathers or the betrothed who out of spite often handed them over to the local Roman authorities.

One example was Lucy who was martyred in Syracuse during the persecution of Diocletian in 304 as her betrothed betrayed her to the authorities when Lucy gave away many of her possessions to the poor, which he believed should have been given to him.

One example was Lucy who was martyred in Syracuse during the persecution of Diocletian in 304 as her betrothed betrayed her to the authorities when Lucy gave away many of her possessions to the poor, which he believed should have been given to him.

Her name means "light", and as her feast day falls at the darkest time of the year, she has been associated with the one true Light who came into the world to cast out all darkness.

Another was Agnes, martyred in the same year as Lucy but in Rome. Although barely 13 years old she faced death with an extraordinary maturity. She refused an arranged marriage as she had already consecrated her virginity and dedicated her life completely to Christ. She preferred death of body in preference to desecrate her virginity. Ambrose in a sermon on Virginity honoured this child-martyr on her feast day for suffering so bravely in such a small body.

Another was Agnes, martyred in the same year as Lucy but in Rome. Although barely 13 years old she faced death with an extraordinary maturity. She refused an arranged marriage as she had already consecrated her virginity and dedicated her life completely to Christ. She preferred death of body in preference to desecrate her virginity. Ambrose in a sermon on Virginity honoured this child-martyr on her feast day for suffering so bravely in such a small body.

"There was not even room in her little body for a wound. Though she could barely receive the sword's point, she could overcome it. Girls of her age tend to wilt under the slightest frown from a parent. Pricked by a needle, they cry as if given a mortal wound. But Agnes showed no fear of the blood-stained hands of her executioners. She was undaunted by the weight of clanging chains. She offered her whole body to the sword of the raging soldiers. Too young to have any acquaintanceship with death, she nevertheless stood ready before it. Dragged against her will to the altar of sacrifice, she was ready to stretch out her hands to Christ in the midst of the flames, making the triumphant sign of Christ the victor on the altars of sacrilege. She was even prepared to put her neck and hands into iron bands - though none of them was small enough to enclose her tiny limbs.

She stood still, praying, and offered her neck. You could see the executioner trembling as though he were himself condemned. His right hand began to shake, and his face drained of colour aware of her danger, though the child herself showed no fear. In one victim then, we arc given a twofold witness in martyrdom, to modesty and to religion. Agnes preserved her virginity and gained a martyr's crown."

She stood still, praying, and offered her neck. You could see the executioner trembling as though he were himself condemned. His right hand began to shake, and his face drained of colour aware of her danger, though the child herself showed no fear. In one victim then, we arc given a twofold witness in martyrdom, to modesty and to religion. Agnes preserved her virginity and gained a martyr's crown."

The patron of music, Cecilia, was a little different in that she went ahead with the marriage arrangement but remained a virgin. On her wedding night she told her husband the following.

The patron of music, Cecilia, was a little different in that she went ahead with the marriage arrangement but remained a virgin. On her wedding night she told her husband the following.

"I have an angel that loveth me which ever keepeth my body whether I sleep or wake and if he may find that ye touch my body by vilainy or foul and polluted love, certainly he shall anon slay you, and so should ye lose the flower of your youth and if so be that thou love me in holy love and cleanness, he shall love thee as he loveth me and shall show to thee his grace."

Upon hearing this, her husband, Valerian, wanted to be able to see the angel, and so Cecilia gave him the following advice:

"If thou wilt believe and baptize thee thou shalt well now see him. Go then forth to Via Appia which is three mile out of this town and there thou shalt find Bishop Urban with poor folks. And tell him these words that I have said. And when he hath purged you from sin by baptism, then when ye come again ye shall see the angel."

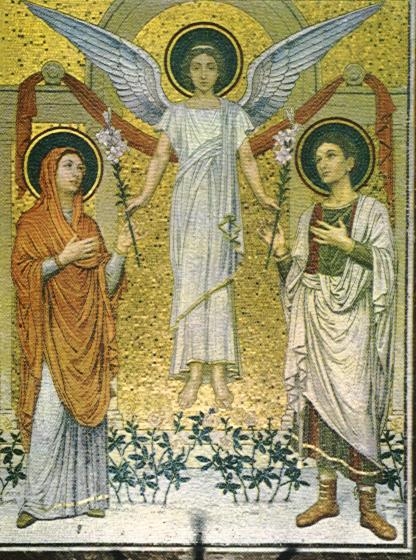

So Valerian did as Cecilia had suggested, and when he returned home he saw her conversing with an angel who was holding two crowns of roses and lilies in his hand which he placed on both their heads. The Angel offered Valerian one petition which he would fulfil. So he asked that his pagan brother may also know of this joy. He too was baptised by Urban.

So Valerian did as Cecilia had suggested, and when he returned home he saw her conversing with an angel who was holding two crowns of roses and lilies in his hand which he placed on both their heads. The Angel offered Valerian one petition which he would fulfil. So he asked that his pagan brother may also know of this joy. He too was baptised by Urban.

Cecilia welcomed Christians into her home, a home-church situation, and soon the two men were found burying the bodies of martyred Christians in Rome. As a result they too were beheaded. Cecilia buried these two martyrs and as a consequence was brought before the prefect. She refused to sacrifice, and consequently she too was sentenced to death. She also was beheaded but even with three strikes he neck was not severed completely and so she lingered on for another three days during which she preached the Faith and sent many to Urban to be baptised. Urban and his deacons buried her body among the bishops and hallowed her home in to a church. Her martyrdom took place c. A.D.230.

In the 5th century. devotion to Cecilia gained great popularity by Christians, a popularity which has continued. In the 16th century she was made the patron saint of musicians, probably derived from the antiphon from her Acts. "As the organs were playing, Cecilia sung to the Lord." Both poetry and music have been written for her. Gounod's Mass for St. Cecilia's Day is very beautiful, and Purcell and Handel wrote music to commemorate her day on 22nd November. The poets, Dryden and Pope wrote Odes to her.

In the 5th century. devotion to Cecilia gained great popularity by Christians, a popularity which has continued. In the 16th century she was made the patron saint of musicians, probably derived from the antiphon from her Acts. "As the organs were playing, Cecilia sung to the Lord." Both poetry and music have been written for her. Gounod's Mass for St. Cecilia's Day is very beautiful, and Purcell and Handel wrote music to commemorate her day on 22nd November. The poets, Dryden and Pope wrote Odes to her.

The Eastern Church had female martyrs too. One was Saint Antonia of Nicaea who in A.D.306 was charged with insulting the pagan gods. Upon her refusal to offer incense to the Roman deities, she was stripped and hanged by her arms. Then her tormenters tore her sides with rakes. Remaining steadfast in her faith, Antonia was finally placed into a sack and drowned in a nearby lake.

The Eastern Church had female martyrs too. One was Saint Antonia of Nicaea who in A.D.306 was charged with insulting the pagan gods. Upon her refusal to offer incense to the Roman deities, she was stripped and hanged by her arms. Then her tormenters tore her sides with rakes. Remaining steadfast in her faith, Antonia was finally placed into a sack and drowned in a nearby lake.

Of course there were many other female martyrs during those spasmodic persecutions until A.D.313. The blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church, and we cannot underestimate the women's contribution to this.

Of course there were many other female martyrs during those spasmodic persecutions until A.D.313. The blood of the martyrs was the seed of the church, and we cannot underestimate the women's contribution to this.