A cold coming we had of it.

Just the worst time of the year

For a journey, and such a long journey:

The ways deep and the weather sharp,

The very dead of winter.

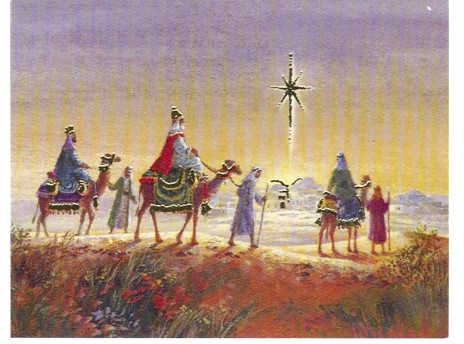

The star of Christmas has become associated with a particular visit made by those eastern kings who travelled a long distance over hazardous terrain and dangerous territory to reach the little village of Bethlehem. These visitors have become known as the magi or the wise men, and they and their trip have been immortalised by Thomas Eliot in the first of his Ariel Poems, titled Journey of the Magi. The opening five lines as above are a direct quote from Andrewes' Nativity sermon for 1622.

Lying down in the melting snow.

The summer palaces on slopes, the terraces,

Then the camel men cursing and grumbling

And the night- fires going out, and the lack of shelters,

And the villagers dirty and charging high prices:

A hard time we had of it.

At the end we preferred to travel all night,

Sleeping in snatches,

With the voices singing in our ears, saying

That this was all folly.

Eliot's Journey of the Magi is indeed worth reflecting upon time and time again for its own spiritual worth, and its portraying the message based on Andrewes' two sermons on the magi that once one sets out to find Christ that journey will often be "hard and bitter"; there will be many "deaths" along the road before Christ is finally embraced. Yet that finding does not bring satisfaction but a disturbing uneasiness. That is the nature of the pilgrimage to our native home.

So the magi undertook to discover Truth, which they found wrapped in swaddling clothes. But as they were learned men their journey revealed that Christ's birth, humble as it was, was not only for the simple, but also for the learned. Thus "Christ is not only for russet cloaks, shepherds and such; ... but even the grandees, great states such as these, venerunt, they 'came' too; and when they came were welcome to Him. For they were sent for and invited by this star, their star properly." Thus applying knowledge and learning should never be a barrier to humility. As Andrewes expresses it, "The shepherds were a sort of poor simple men altogether unlearned. But here come a troop of men of great place, high account in their country; and withal of great learned men, their name gives them for no less. ... [Hence] wealth, worth, or wisdom shall hinder none, but they may have their part in Christ's birth as well as those of low degree."

Another important aspect of the magi's coming was that unlike the shepherds' they belonged to the Gentile world, and accordingly manifested that Christ's coming was for all. In that sense they represented us at Christ's Nativity. Hence Andrewes encourages us to "look out," and see "if we can see this star. It is ours, [as] it is the Gentiles' star. We may set our course by it, to seek and find, and worship Him as well as they."

Although the magi have come to represent us in following the star, Andrewes posed, if we were left to our devices to follow this new heavenly light to find the Christ-child, would we have come? And if we decided we would make the journey, would we go immediately or would we have hesitated or even postponed it? For the magi there was no hesitation despite its timing "at the worst time of the year". "They set forth this very day. ... So desirous were they to come ... and to be there as soon as possibly they might; broke through all these difficulties."

It was but vidimus, venimus, with them; no sooner saw, but they set out presently. So as upon the first appearing of the star, ... it called them away, they made ready straight to begin their journey this morning. A sign they were highly conceited of His birth, believed some great matter of it, that they took all these pains, made all this haste that they might be there to worship Him with all the possible speed they could. Sorry for nothing so much as that they could not be there soon enough, with the very first, to do it even this day, the day of His birth.

If we had decided to make the journey, would it have been as swift as that of the magi? Not likely, thought Andrewes.

It would have been but veniemus at the most. Our fashion is to see and see again before we stir a foot, specially if it be to the worship of Christ. Come such a journey at such a time? No; but fairly have put it off to the spring of the year, till the days longer, and the ways fairer, and the  weather warmer. ... Our Epiphany would sure have fallen in Easter-week at the soonest.

weather warmer. ... Our Epiphany would sure have fallen in Easter-week at the soonest.

They were no sooner come, but they spake of it so freely, to so many, as it came to Herod's ear and troubled him not a little that any King of the Jews should be worshipped beside himself. So then their faith is no bosom-faith, kept to themselves without saying anything of it to anybody. ... The star in their hearts cast one beam out at their mouths. And though Herod who was but Rex factus could evil brook of Rex natus, must needs be offended at it, yet they were not afraid to say it. ... So neither afraid of Herod, nor ashamed of Christ; but professed their errand, and cared not who knew it. This for their confessing Him boldly.

Thus the magi by their example revealed the difference between "fidelis, well-grounded" faith, and "credulus, lightness of belief." In seeing the new star, assisted "by the light of their prophecy," they immediately believed this star herald some significant happening. They did not stand still and simply gaze at the star; but it was like the morning light drawing them, urging them and bringing them to the place where Jesus was born, and so Andrewes prompts us to see the star and to do likewise. "But by this we see, when all is done, hither we must come for our morning light." Once we "have seen His star", it is important that He sees that our star burns in us through the faith implanted by the Holy Spirit as it did in the magi. "Vidimus stellam is as good as nothing without it." Andrewes explained:

There must be a light within the eye; else ... nothing will be seen. And that must come from Him, and the enlightening of His Spirit. ... He sending the light of His Spirit within into their minds, they then saw clearly, this the star, now the time, He the Child who this day was born.

Thus "the light of the star in their eyes, the 'word of prophecy' in their ears, the beam of His Spirit in their hearts; these three made up a full vidimus."

The faith of the magi kindled by the heavenly star suggested another star for Andrewes It is what St. Peter called the "'Day-star which rises in the heart,' that is faith, which shined and manifested itself by their labour in coming, diligence in enquiring, dutying in worshipping." And of course there was another star, a third star, the brightest star, "Christ Himself, 'the bright morning star,' whom both the other guide us to; the Star of this morning which makes the day the greatest day in the year."

All three stars hearken venite adoremus, which is what the magi did. They were no sooner with the Christ-child than they fell down and worshipped Him and offered their gifts. Christ invites us to "come and seek, and find and worship Him, that is do as these did." However Andrewes has doubts about our venite adoremus. We are full of all kinds of excuses, even though our journey to Bethlehem is so, so much shorter and so simple in comparison to that of the magi. "What excuse shall we have if we come not? If so short and so easy a way we come not, as from our chambers hither, not to be called away indeed? Shall not our non venerunt have an ecce." No says, Andrewes, our attitude to worship Christ is so different from that of the magi. Even when we do come, Andrewes declares, we have no urgent desire to adore Him, bow down and give Him His worth. Yet to be Christ's faithful servants, "We must learn ... to ask where He is, which we full little set ourselves to do. If we stumble on Him, so it is; but for any asking we trouble not ourselves, but sit still as we say, and let nature work; and so let grace too, and so for us it will." However Andrewes warns that "Christ has His ubi, His proper place where He is to be found; and if you miss of that, you miss of Him. And well may we miss, says Christ Himself."

Andrewes then asked:

The star changed the live of the magi as evident in the last lines of Eliot's poem.

We returned to our places, these Kingdoms,

But no longer at ease here, in the old dispensation,

With an alien people clutching their gods.

I should be glad of another death.